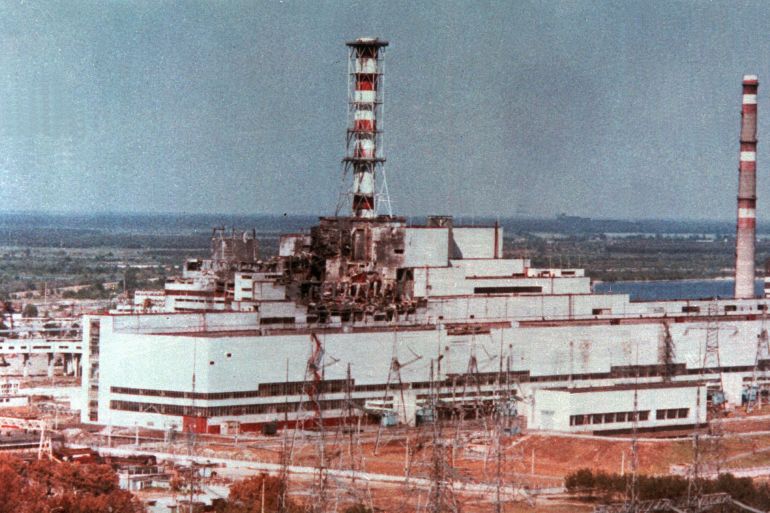

Could Ukraine’s nuclear industry face another Chernobyl?

Thirty-five years after the disaster, the nuclear industry is Ukraine’s most reliable economic lifeline. But critics say it faces a perennial crisis caused by corruption, safety problems and politicised decision-making.

Kyiv, Ukraine – The radioactive cloud that briefly hovered over most of Europe after the April 26, 1986 explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power station had, after all, a silver lining, Petro Kotin says.

Thirty-five years after a botched security test caused the worst nuclear disaster in history, he is at the helm of Energoatom, a state-run consortium in charge of Ukraine’s four nuclear stations and their 15 reactors.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUkraine-Turkey cooperation has its limits

Russia, Ukraine to expel diplomats amid rising tensions

Ukraine may seek nuclear weapons if left out of NATO: Diplomat

“We are unique because no other nation has the practical experience of overcoming such a disaster,” Kotin, who was appointed as Energoatom’s acting president in March 2020, told Al Jazeera in his office in central Kyiv.

The stations he manages generate half the electricity for the ex-Soviet nation of 43 million people, placing Ukraine on the list of the world’s top-10 nuclear energy producers.

“To say today that our nuclear energy generation is weaker because we had Chernobyl is completely stupid,” Kotin, a vivacious 60-year-old, said. “On the contrary, we improved our nuclear potential, our knowledge, our skills, our attitude towards security because of this disaster.”

While several European nations and Japan are phasing out nuclear energy or reducing their reliance on it, Ukraine’s struggling economy simply has no alternative.

After annexing Crimea in 2014, Moscow backed separatists in two southeastern provinces where most of Ukraine’s coal used for energy generation is mined. The Kremlin also spiked natural gas prices, hobbling Ukraine’s outdated, energy-inefficient industries and burdening average Ukrainians with hefty heating bills.

The nuclear industry remains Ukraine’s most reliable economic lifeline.

But domestic and international critics claim that the industry faces a perennial crisis caused by corruption; safety problems with ageing, worn reactors; disruption of ties with a Russian nuclear monopoly; and a politicised switch to US-made nuclear fuel.

Industry insiders, environmentalists and politicians claim that the construction of a spent fuel storage facility near the capital, Kyiv, and the proximity of Europe’s largest nuclear station in the southern city of Zaporizhzhia to Europe’s hottest armed conflict add to their concerns about the possibility of a nuclear incident, particularly in a nation that went through two popular uprisings since 2005 and lost a chunk of its territory to Russia.

Hexagonal vs square

More than 400 nuclear reactors generate electricity worldwide in a way similar to any thermal power station.

The fission in nuclear fuel rods warms a coolant, usually water, that heats an electricity-generating steam turbine. Thermal stations need coal, diesel or natural gas, while uranium rods stay hot for years or decades emitting no air-polluting gases.

Sounds simple. But uranium dioxide sealed in zirconium alloy tubes in the rods emits radiation that has to be contained in hermetically sealed reactors. Ukraine’s Soviet-designed rods are hexagonal, resembling bee cells, while Western-made rods are square.

The switch is far from simple – but necessary, because Rosatom, Russia’s nuclear monopoly that charged Ukraine hundreds of millions of dollars a year, is controlled by the Kremlin. And the Kremlin has a well-known proclivity to use energy supplies as a political cudgel.

In 2005, Ukraine’s first anti-Russian uprising, dubbed the Orange Revolution, installed a pro-Western government that immediately started looking for ways to wean the nuclear industry off the Russian fuel.

It chose Westinghouse Electric Company LLC, a Pittsburg-based nuclear energy giant. Some experts and politicians warned that Westinghouse-made fuel rods may unseal and potentially cause a reactor to melt.

“The switch to Westinghouse fuel is potentially dangerous,” Oskar Njaa, the Russia and Eastern Europe adviser for Bellona, a Norway-based nuclear industry monitor, told Al Jazeera.

In 2012, Westinghouse fuel rods had to be removed from the South Ukrainian power station after protective envelopes in two reactors were damaged.

Ukraine asked Rosatom for fuel and help – prompting Russian President Vladimir Putin to remark gloatingly that Rosatom experts had “to solve complex technical problems, take [the Westinghouse fuel] out and load the Russian fuel back in”.

Ukraine’s losses amounted to $175 million, Mikhail Gashev, Ukraine’s top nuclear safety inspector at the time, claimed – and banned the use of Westinghouse fuel.

Ukrainian experts doubted his assessment, and his decision was overturned after he was fired among hundreds of pro-Russian officials following Ukraine’s second anti-Russian popular uprising, the 2014 Revolution of Dignity.

Former Prime Minister Nikolay Azarov, another pro-Russian political figure who fled Ukraine after the revolt, said in 2017 that the decision was made “in spite of Ukraine’s security interests”.

Westinghouse modified the rods – and no further incidents were reported.

“That might be a sign of a better culture for safety and security in the industry,” Njaa said adding that his group is, however, “worried that incidents might become more severe and greater in numbers due to the ageing equipment at the plants.”

In 2018, the then-energy minister Ihor Nasalyk declared that Ukraine “overcame its dependence” on Rosatom’s fuel.

Not exactly. By 2020, only six of Ukraine’s 15 reactors have been loaded with Westinghouse fuel, and the seventh one will be loaded later this year.

However, the diversification of fuel supply is a fact. “This is a matter of energy security, a matter of politics, a matter of economics too. No one can twist our arms saying, ‘We won’t supply the nuclear fuel and you’ll have no electricity in the winter’,” Energoatom’s Kotin said.

Apart from the fuel, observers are also concerned about Ukraine’s ageing, worn reactors, 12 of which began operating in the 1980s and were supposed to be shut down in 2020. But Energoatom extended their lifespan spending hundreds of millions on each, thanks largely to loans from the European Union.

This is a common practice worldwide – the average lifespan of almost 100 nuclear reactors in the US is 40 years, and 88 have been approved for another 20 years. But some experts are worried about the safety measures and upgrades.

“What we witness every time a decision [to extend the lifespan] is made, some of the safety upgrades have either not been made or have not been made in full,” Iryna Holovko, the Ukraine coordinator for Bankwatch, a Prague-based environmentalist group, told Al Jazeera.

Bankwatch has for years been urging Ukraine to stop extending the lifespan of its “zombie reactors” without correcting “safety deviations” and detailed assessments of all the environmental risks for the people living around the stations and in neighbouring nations.

But Kotin dismisses their claims as a “manipulation with facts”.

In the 35 years since the disaster, after countless visits from Western security consultants and the tireless work of thousands of Ukrainian experts, the nuclear industry completely revised its security guidelines and organisational structure, he said.

Each of the 15 operational reactors has been modified and is now hermetically sealed, with five protective layers between the fuel and the atmosphere. Hundreds of security drills have taken place – and are planned in the years to come.

Spent fuel needs dumping

As soon as fuel rods in a nuclear reactor are not hot enough to generate steam, they are placed in cooling ponds adjacent to any nuclear power station.

They remain there for years, keeping the water warm (in the Chernobyl cooling pond, water still does not freeze in the winter, and giant catfish lived there until 2019).

Then the rods can be processed or stored safely for thousands of years.

The fuel switch brought about another problem; unlike Rosatom, Westinghouse does not take the spent fuel back for processing or storage.

Until December, Ukraine had two pretty problematic storage facilities – and an unfinished third one. One at the shut-down Chernobyl station is almost full. At the second one, an open-air yard outside the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant, thousands of spent fuel rods are stored in ventilated concrete containers. In 2014, the plant was about 200 kilometres (125 miles) southwest of the front line of the separatist conflict.

The sight was horrifying to a visiting expert.

“I suddenly stood in front of the utterly unprotected interim storage,” Patricia Lorenz of Friends of the Earth, an environmentalist group that visited the plant on a fact-finding mission in 2014, told Al Jazeera. “It is basically unprotected against war and terrorism, while the front was close by back then.”

In May 2014, the station’s security and police turned away dozens of armed and masked far-right nationalists who tried to enter the plant to “protect” the station from the separatists.

Since then, the front line has moved eastward, and in December, Energoatom opened a third facility a mere 70 kilometres (43 miles) north of Kyiv, in the Chernobyl exclusion zone that is scheduled to receive the first batch of spent fuel in June.

But plans to transport spent fuel via Kyiv, the city of more than two million, drew sharp criticism.

“This will be happening in a country where everything turns upside-down, collides, explodes, and where lawlessness rules,” Kyiv-based environmentalist Vladimir Boreiko told reporters.

Years not misspent

Kotin had just turned 22 when he was a summer intern at the Chernobyl nuclear power station in 1983, three years before the disaster.

“After [the explosion] happened, I recalled the situations I was in during my internship in 1983, and I had this feeling of utter horror,” he recalled.

The explosion was hundreds of times more powerful than the 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, contaminating an area the size of the United Kingdom in what is now Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.

More than 100,000 people were evacuated from the area, and some 1,000 square kilometres (390 square miles) of the most polluted land were cordoned off and fenced with barbed wire, becoming the “exclusion zone” that will remain uninhabited for tens of thousands of years.

Thousands of firefighters, emergency workers and soldiers ordered to clean up the debris died after containing the explosion, up to 200,000 Ukrainians, Belarusians and Russians died of Chernobyl-related cancers and other diseases, Greenpeace said in 2006.

In the disaster’s aftermath – and considering the risks of terrorism, natural disasters and military invasions – security measures also included a calculation of risks.

Among them were the fall of a passenger plane on a station and the disastrous flooding of the Dnieper, Ukraine’s mightiest river and main waterway, all the way down to the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station, where Kotin worked between 1985 and 2020 – first, as an engineer, and last, as director-general.

Corrosive corruption

The 35 years that have passed since the Chernobyl explosion have also brought with them another problem the Soviet nuclear industry never faced: corruption. The nature of a planned economy and constant control of intelligence agencies under the Soviet Union made graft nearly impossible in the industry, but post-Soviet Ukraine became a hotbed of corruption.

In 2020, Ukraine ranked 117 in the worldwide list of 180 nations in the Corruption Perceptions Index compiled by Transparency International, an international corruption monitor – higher than Russia with its number 129 spot.

A string of corruption scandals tainted the industry in post-Soviet Ukraine.

Observers, anti-corruption activists and industry insiders have for years claimed that some Energoatom officials are allegedly corrupt – and their non-transparent deals such as procurement of low-quality equipment may result in a disaster. Occasionally, they face real charges.

In July 2017, the managers of the Southern-Ukrainian nuclear power plant “deliberately purchased counterfeit electric equipment” that could have caused “an emergency of techno-genic character”, according to a laconic statement by the SBU, Ukraine’s Security Service. However, there were no further statements or media reports on the case.

Last October, an explosion in the courtyard of Ukraine’s Supreme Constitutional Court damaged the building’s facade, and the judges claimed it was masterminded by the supporters of former lawmaker and top energy official Mykola Martynenko, who was closely allied with former presidents and prime ministers.

In 2015, Ukraine’s anti-corruption bureau accused him of receiving 6.5 million euros ($7.9m) in kickbacks from Energoatom for “helping” arrange contracts to supply equipment from a Czech company. Last June, a Swiss court found him guilty of laundering 2.8 million euros ($3.4m), but his case in Ukraine drags on and on. Martynenko pleaded not guilty.

Even the current team faces corruption allegations.

Last July, Kotin fired Oleh Polishchuk, a whistle-blowing Energoatom official, who complained about purported corruption deals to anti-corruption investigators. In October, Ukraine’s top anti-corruption bureau urged Prime Minister Denys Shmygal to order an investigation into the allegations, and in March, a Kyiv court ruled that the dismissal was illegal.

An industry insider openly accused Kotin’s team of alleged involvement in non-transparent deals, hiding financial information and firing experienced technical staffers and managers.

“They get crazy kickbacks. This is a team of marauders,” Olga Kosharna, an independent nuclear safety expert with decades of experience in the state inspection for nuclear regulation, told Al Jazeera.

Relying on her extensive contacts and unmatched insider information, she insists that corruption is the biggest safety threat to Ukraine’s nuclear industry.

What if there is “an equipment failure if you bought the wrong spare part?” she said.

Kotin brushed off her allegations. “All of her words and publications are fakes, lies, they are untrue and slanderous,” he said.

Mansur Mirovalev grew up in a family of nuclear physicists and covered Russia’s nuclear industry and the consequences of the Chernobyl disaster.