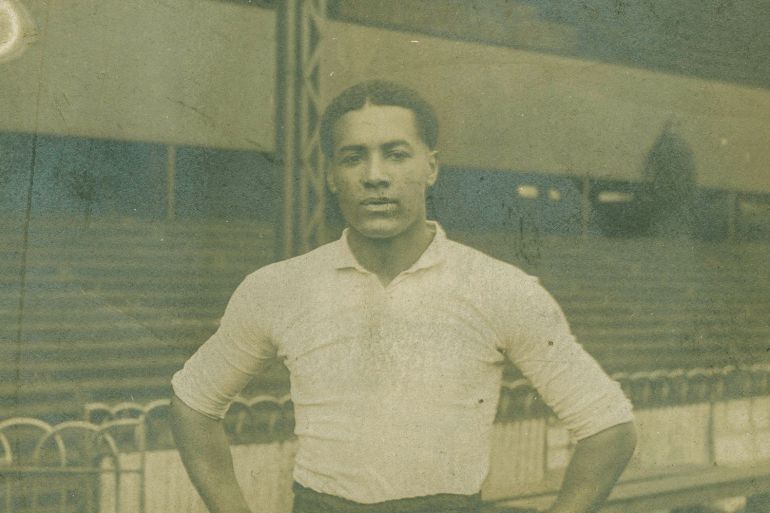

Walter Tull: The footballer who became a war hero

As one of British football’s first Black players, Walter Tull was a trailblazer. But when World War I broke out, he became the first Black officer in the British army to lead a battalion.

Earlier this year, 43,000 people gathered at Rangers’ Ibrox Stadium in Glasgow for a pre-season friendly. The game between Tottenham Hotspur and Rangers was to honour the memory of a footballer who had died more than 100 years earlier.

Walter Tull’s life had been extraordinary – a “testament”, according to Phil Vasili, the author of his biography, “to a determination to confront those people and those obstacles that sought to diminish him and the world in which he lived”.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFIFA World Cup 1938: Italy defend title before WWII breaks out

World Cup 1954: West Germany, Hungary and the Miracle of Berne

World Cup 1958: When Pele guided Brazil to its first title

Tull was born in the coastal town of Folkestone, England, in April 1888. His father, Daniel Tull, was a Black carpenter from Barbados whose parents had been enslaved. His mother, Alice Elizabeth Palmer, was a local white woman.

By the time Tull was nine, both of his parents had died. So he and his brother, Edward, were sent to live in an orphanage in east London’s Bethnal Green. When Edward was later adopted by a family in Glasgow, Scotland, Tull was left alone.

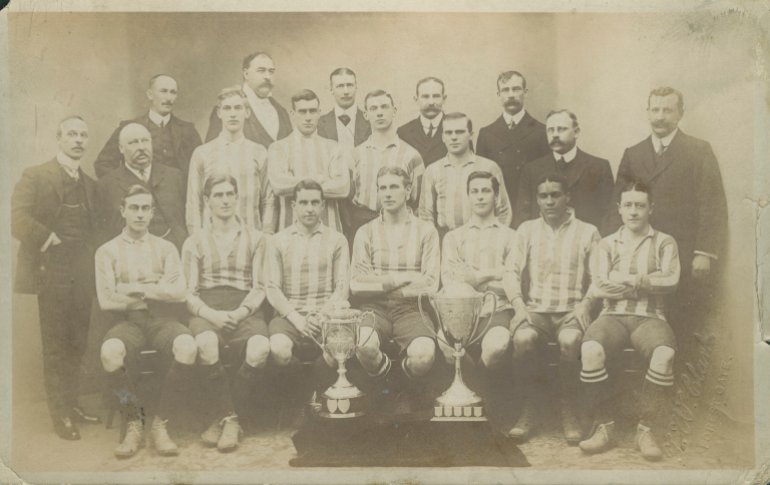

He sought solace in the orphanage football team, where his skills caught the attention of the local amateur side, Clapton FC. Tull joined them in October 1908 and quickly inspired them to win the FA Amateur Cup, London County Amateur Cup and London Senior Cup. The Football Star, a London journal, proclaimed him the “catch of the season”.

Soon, one of the biggest clubs in the country came calling. In the summer of 1909, Tull signed for Tottenham Hotspur, becoming only the third player of mixed-racial heritage to appear in the top tier of English football, the First Division.

Playing at inside forward, his first two games for Tottenham were against Sunderland and the FA Cup holders Manchester United. In his brief stay in north London, Tull scored two goals in 10 games and was hailed by The Football Star as “Hotspur’s most brainy forward … so clean in mind and method as to be a model for all white men who play football”.

But just 0.04 percent of the population of Edwardian Britain was Black, and Tull faced racism from the stands.

There was one game at Bristol City in October 1909, when Tull was relentlessly abused. The Football Star reported that “a section of the crowd made a cowardly attack on him in language lower than Billingsgate” – a word that had become synonymous with foul language like that used centuries earlier at the London fish market.

Tottenham responded by dropping Tull into their reserves team. It is unclear whether they intended this to be for his own protection or if the decision was taken to appease the racist mobs, but Tull languished there for two years, until Northampton Town, a team in the Southern Football League, signed him in October 1911.

Herbert Chapman, the manager who signed Tull, was in his first football management job. He would go on to establish himself as one of English football’s greatest-ever managers, winning four First Division titles with his famous Huddersfield Town and Arsenal sides in the 1920s and 1930s. Tull would go on to play 111 games for Northampton before his career was interrupted in the summer of 1914 by the outbreak of the First World War.

From football field to battlefield

In December of that year, Tull enlisted in the 17th battalion of the Middlesex Regiment of the British army. Known as the Footballers’ Battalion, it had been formed to show that professional football was contributing to the war effort. By the spring of 1915, around 200 professional footballers had enlisted in the battalion. They were joined by club staff, amateur players and even fans who wanted to fight alongside the players they were used to watching from the terraces.

Tull arrived in France in November 1915. Towards the end of 1916, he fought in the Battle of the Somme, in which more than one million soldiers were killed or wounded over four months. The British army, alone, sustained approximately 420,000 casualties, including 125,000 deaths. Tull survived but suffered “shell shock” and was sent home to England to recuperate.

By this time, Tull had so impressed his senior officers that before returning to France, he was sent to the officer cadet training school in Gailes, Scotland, which defied the military’s regulations that forbade “any negro or person of colour” from being commissioned as an officer. The army ignored their own rules to make the most of Tull’s talents.

It was while Tull was in Scotland that he was approached by Rangers, who signed him to play for them when the war was over.

By May 1917, he had risen to the rank of second lieutenant. Between November of that year and March 1918, he served on the Italian front, where he led 26 men on a night raid during the Battle of Piave River. Tull crossed the river in northern Italy into enemy territory with his troops before returning without sustaining any casualties, earning praise for his “gallantry and coolness” under heavy fire.

“He made a mockery of the firmly held view of the Army Council that white rank-and-file soldiers would not take orders from a Black man,” Tull’s biographer Vasili said. “[He was] a soldier that inspired such love in contradiction of ‘common sense’ notions and official rules and regulations.”

Tull moved to northern France on March 8, 1918, with the 23rd battalion to be stationed near Arras. In the early hours of March 21, before the sun had risen, the Germans began to bombard the British and French troops in what was their spring offensive and their last concerted effort to win the war.

Over the course of five hours, 6,600 German guns fired 3.5 million explosive shells onto British and French positions. Caught unaware, the British were forced to fight back in a defensive action that would last for four months and see them suffer 418,000 casualties. Among them, was Walter Tull.

On March 25, 1918, Tull was shot and killed during the First Battle of Bapaume near the village of Favreuil in the Pas-de-Calais.

Under heavy fire, Private Tom Billingham, a former goalkeeper for Leicester Fosse, attempted to retrieve Tull but was unsuccessful. His body was never found.

Ridiculing ‘barriers of ignorance’

The name of one of the first Black players in British football and the first Black officer in the British army to lead a battalion of troops can be found engraved on the Arras Memorial in France alongside those of 34,794 other soldiers who lost their lives but did not receive a proper burial.

The commanding officer of Tull’s Battalion, Major Poole, declared that he would be put forward for a Military Cross, one of the British army’s highest honours, but he never received it. Vasili believes he has found evidence in the form of a top-secret memo that explains the army’s reluctance to acknowledge Tull. In the memo, which includes highly racist language, the British army’s head of recruitment in New York stated, “We now refuse to post coloured men to ‘white units’.”

It may have been a final example of the racism directed at a man who, according to Vasili, “ridiculed the barriers of ignorance that tried to deny people of colour equality with their contemporaries”.

It took many decades, but Tull would be remembered. In 1999, a memorial to him and a remembrance garden were created outside Northampton Town’s Sixfields Stadium, while Walter Tull Way and a nearby pub were also named after him.

In October 2021, Tull was inducted into the National Football Museum’s Hall of Fame at a ceremony in Manchester attended by his great-grandnephew Edward Finlayson and the former Tottenham and England defender Ledley King.

“Ever since I found out about Walter Tull as a young player at Spurs, I’ve been a big fan,” King said. “He is a true inspiration to me and a pioneer for every Black footballer who has come through since.”