Unpack the past: Mandela, the keffiyeh and South Africa’s Palestine embrace

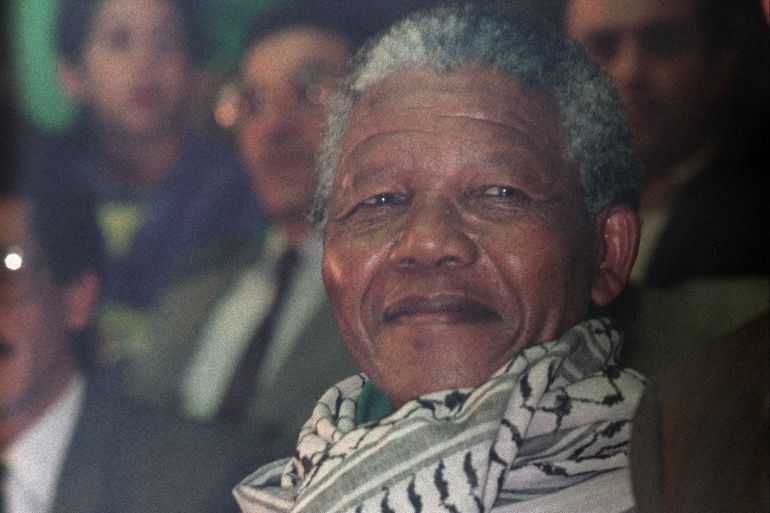

Ten years after the anti-apartheid icon passed away, his embrace with Yasser Arafat and his donning of the keffiyeh remain powerful symbols of South Africa’s special warmth towards Palestine.

In late February 1990, 16 days after his release from prison, Nelson Mandela descended the steps of a plane in Lusaka, Zambia, which was home to the African National Congress’s exiled leadership at the time. A who’s who of leaders sympathetic to the ANC cause – from Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda to Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe – greeted the anti-apartheid leader with smiles and handshakes.

But the most emotional embrace of all came from a short, stout man with his trademark keffiyeh wrapped around his head: Yasser Arafat, the leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Pulling the 6-foot-4-inch tall Mandela’s face down towards him, Arafat placed kisses on Mandela’s cheeks.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsHistory Illustrated: Mandela – South Africa’s First Black Preside

South Africans demand permanent Gaza ceasefire during pro-Palestine march

Mandela would reciprocate that show of support in his own way three months later, when he attended a summit in Algiers wearing the Palestinian keffiyeh. While it is unclear where he got it or why he chose to wear it that day, it could not have been an accident – Mandela was notoriously deliberate about how he dressed.

Mandela’s ghostwriter Richard Stengel observed: “Mandela was always aware of his own image. His sense of this was curiously modern, far ahead of what his colleagues and enemies understood at the time.”

In 1962, after being charged with leaving the country illegally, Mandela – known for his smart suits and shiny shoes – arrived in court in a jackal-skin kaross, a beaded necklace and a shoulder bracelet. His new wife Winnie, also clad in traditional Xhosa attire, cheered him on from the public gallery. He knew exactly what he was doing. As Mandela wrote: “It was to assert myself. To go to the white man’s court as an African, wearing my own outfit and not the one that is desired by court.”

In 1995, a year after becoming the first democratically elected president of South Africa, Mandela famously wore the Springbok rugby jersey – for many, a symbol of apartheid – to present Francois Pienaar with the Rugby World Cup trophy. This time, his goal was to mend the divisions in his fractured nation.

Mandela felt a special bond with the Palestinian people. In 1997, while still president of South Africa, he said the ANC’s struggle was ongoing. “We know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians.”

In 2004, after the death of Arafat, he paid tribute to the leader of the PLO: “He was an icon in the proper sense of the word. He was not only concerned with the liberation of the Arab people but of all the oppressed people throughout the world – Arabs and non-Arabs – and to lose a man of that stature and thinking is a great blow to all those who are fighting against oppression.”

Three years after Mandela’s death on December 5, 2013, the people of Palestine repaid the favour by unveiling a giant statue of the South African leader in the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah.

That sentiment of warmth – and the iconic imagery of Mandela and the keffiyeh – returned to underscore the nature of South Africa’s relationship with the Palestinian struggle after the October 7 Hamas attack on southern Israel.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa condemned that attack, but as Israeli bombs began killing thousands of innocent people in Gaza, he stepped in front of cameras, wearing a black and white keffiyeh around his neck, and holding a small Palestinian flag in his hand.

“They [the Palestinian people] have been under occupation for almost 75 years … waging a struggle against an oppressive government that has occupied their land, but also a government that has in recent times been dubbed an apartheid state,” he said.

Birth of a bond

There is no evidence, says historian Thula Simpson, that Mandela identified himself with the Palestinian cause before his imprisonment in 1963. In fact, when he established Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the ANC’s military wing, many of his key inspirations were Israeli.

Arthur Goldreich was one of the few in the ANC who had any battlefield experience. As Mandela writes in his autobiography: “In the 1940s, Arthur had fought with the Palmach, the military wing of the Jewish National Movement in Palestine. He was knowledgeable about guerrilla warfare and helped fill in many gaps in my understanding.” Goldreich went on to become a prominent critic of “the ‘abhorrent’ racism in Israeli society”.

In his recent book, Spear: Mandela and the Revolutionaries, Paul S Landau observes that while setting up MK, Mandela read Menachem Begin’s The Revolt: Story of the Irgun, about another Zionist paramilitary force in Palestine. The Irgun, wrote Landau, was even more radical than the Palmach and issued in 1944 “a public call to revolt”. Mandela’s handwritten notes show that he was impressed by their tactics. “The Irgun provided Mandela with an anti-state (anti-British) guerrilla model, and in its penumbra he first recorded the concept of a ‘prolonged struggle’ in connection with a coming guerrilla war,” wrote Landau.

Simpson said, during his 27-year imprisonment, Mandela would have been aware of the support the ANC received from other countries, of Afro-Asian solidarity and the broad strokes of the PLO’s struggle. But detailed knowledge of the South African situation would have been difficult enough to obtain, let alone what was happening in Palestine.

After his release in February 1990, however, he wasted no time in getting up to speed on the ANC’s international relations and expressing his foreign policy views. In June of that year, four years before he became president of South Africa, Mandela was invited to the US by President George HW Bush. At a town hall meeting chaired by ABC News’s Ted Koppel, Mandela was challenged about the public support he had given to leaders like Fidel Castro, Muammar Gaddafi and Arafat, who faced accusations of human rights violations.

Without skipping a beat, Mandela responded: “One of the mistakes which some political analysts make is to think that their enemies should be our enemies.”

The crowd erupted in applause, before finally allowing Mandela to continue: “That we can, and we will never do. We have our own struggle, which we are conducting. We are grateful to the world for supporting our struggle, but nevertheless, we are an independent organisation with its own policy … Our attitude towards any country is determined by the attitude of that country to our struggle. Yasser Arafat, Colonel Gaddafi, Fidel Castro support our struggle to the hilt … Our attitude is based solely on the fact that they fully support the anti-apartheid struggle. They do not support it only in rhetoric. They are placing resources at our disposal, for us to win the struggle.”

Responding, Henry Siegman of the American Jewish Congress expressed “profound disappointment” with Mandela’s answer “because it suggests a certain degree of amorality, that … what these people do in their own countries … is totally irrelevant … as long as they support the cause of the ANC”.

Mandela doubled down, explaining that as a liberation movement involved in its own struggle, the ANC had “no time to be looking into the internal affairs of other countries”. As far as Arafat and the PLO were concerned, Mandela explained that “we identify with the PLO because, just like ourselves, they are fighting for the right of self-determination”.

He added: “The support for Yasser Arafat in his struggle does not mean that the ANC has ever doubted the right of Israel to exist as a state, legally. We have stood quite openly and firmly for the right of that state to exist within secure borders. But, of course … We carefully define what we mean by secure borders. We do not mean that Israel has the right to retain the territories they conquered from the Arab world, like the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights and the West Bank. We don’t agree with that. Those territories should be returned to the Arab people.”

ANC and foreign policy

Historian Matthew Graham says South Africa’s foreign policy is a product of the ANC’s history. “The ANC’s support networks in exile crossed the Cold War divide,” he explained. “The party was very good at talking to anybody and everybody. They had an office in London but were also talking to Gaddafi and Castro and the like.”

But, Graham stressed, “Their real support came from the Eastern bloc. This meant it developed really close relations at the very top of the ANC, which persisted well into the post-apartheid era.” Mandela’s inauguration in 1994, for instance, saw Arafat and Castro sitting a discreet distance away from US Vice President Al Gore and First Lady Hilary Clinton at a time when Washington treated the PLO and Cuba’s communist government as pariahs.

Despite having now been in power for almost 30 years, the ANC still sees itself as a liberation movement whose project is incomplete, Graham said. “They continue to walk a tightrope. They need Western economic help to fix South Africa, yet they talk and project like a radical liberation movement.” This, he is convinced, stems from their history of “talking to all sides”.

Simpson agreed. “The ANC tailored its foreign policy after 1990 on the basis of its experience in the liberation struggle. They view themselves as pushing for a new international order, and the Palestinian struggle as an extension of the ANC struggle.” There is, he adds, “no strictly economic rationale in supporting Cuba, or Palestine … or Russia. It’s more of an affinity, part of a worldview that looks on these as being separate fronts in a shared global struggle.”

‘The end of history’

There is a cruel irony that the ANC’s coming to power coincided with the fall of the Berlin Wall – what Francis Fukuyama famously referred to as “the end of history”. Simpson believed that Mandela and his comrades “felt hemmed in by a new order, which was hostile to the kinds of changes that they wished to engineer within South Africa”. “The ANC was scared of the Washington Consensus and becoming overly reliant on the IMF and Washington.”

Simpson argued that both Bush presidents offered South Africa a deal to act as a “point man” in Southern Africa – but the ANC was reluctant to take it.

He believed the reasons for their refusals were more about domestic affairs than foreign policy. “Under apartheid, state power had been used to create inequality. The struggle was one for power, to overcome inherited, largely socio-economic backlogs.”

And while the ANC assumed political power in 1994, large sections of the economy remained – as some still remain – under white control. “It’s all about the externalisation of an internal struggle,” said Simpson. “Pushing back against a global economic order, buttressed by US military power, and the internal extension of that order, which manifests itself as racialised inequality.”

From the outside, South Africa’s foreign policy can seem incoherent. From a moral standpoint, it is hard to square the government’s abstention from the United Nations vote condemning Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territories with their impassioned support for the Palestinian cause.

But this, Graham said, misses the point. As he wrote in his book, The Crisis of South African Foreign Policy: “There is still a belief that the ANC remains the champion of democracy and human rights ideals, which it itself had so vociferously proclaimed. In reality, nothing could be further from the truth, because when issues of democracy and human rights are pitted against the anti-imperial agenda, the ANC’s anti-imperialism triumphs every time. This only serves to fuel perceptions of incoherence and contradiction.”

The Israel factor

The ANC’s affinity with Palestine is also not surprising given the close ties between Israel and the apartheid government. In the 1930s, the National Party membership card featured the Swastika, and during World War II, BJ Vorster, who went on to serve as South Africa’s prime minister from 1966 to 1978, was jailed for his involvement in the paramilitary wing of the anti-British, pro-Nazi Ossewabrandwag.

In the early days, wrote Sasha Polakow-Suransky, “Israeli leaders’ ideological hostility toward apartheid kept the two nations apart.” In 1963, Golda Meir told the UN General Assembly that Israelis “naturally oppose policies of apartheid, colonialism and racial or religious discrimination wherever they exist”.

But things began to change after the 1967 war, which saw Israel seize territory from its Arab neighbours, tripling its size in just six days. “The settlement project that soon followed planted hundreds of thousands of Jews on hilltops and in urban centers throughout the newly conquered West Bank and Gaza Strip, saddling Israel with the stigma of occupation and forever tarring it with the colonialist brush,” wrote Polakow-Suransky.

The 1973 Yom Kippur War may have been started by a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria, but for the global left, Israel’s fightback and subsequent territorial gains confirmed their status as an oppressor. Egypt also reclaimed some territory. After the Yom Kippur War, wrote Polakow-Suransky, “all but a few African countries severed diplomatic ties with the Jewish state … It wasn’t long before Israel initiated defence cooperation with some of the world’s most notoriously brutal regimes, including Argentina’s military dictatorship, Pinochet’s Chile and apartheid South Africa.”

In 1993, Mandela said the ANC had been “extremely unhappy” with Israel’s collaboration with the apartheid government. The ANC’s senior leadership has not forgotten that many of the weapons the apartheid government used to kill their people were bought from Israel. It has since emerged that Israel even went so far as to offer nuclear warheads to the apartheid regime.

Peace over violence

Like most anticolonial movements, the anti-apartheid struggle grappled with questions of if and when it was appropriate to respond to a brutal state apparatus with violence.

Yet, the ANC itself was founded on principles of non-violence. As the apartheid government ratcheted up its attacks on civilians in the 1950s the organisation maintained its belief in the power of peaceful protest.

It was only in 1961, after being pushed over the edge by the massacre of at least 69 innocent Black people at Sharpeville, that Mandela himself asked the ANC to abandon its policy of non-violence. It took a lot of convincing but eventually the party leadership agreed to the formation of MK.

On December 16, 1961, handbills were scattered in the townships of Port Elizabeth and pasted on lamp posts in Johannesburg: “The people’s patience is not endless. The time comes in the life of any nation where there remain only two choices: submit or fight. That time has now come to South Africa. We shall not submit and we have no choice but to hit back by all means within our power in defence of our people, our future and our freedom.”

That context is vital to understanding comments made by Mandela during a state visit to Palestine in 1999: “Choose peace rather than confrontation. Except in cases where we cannot get, where we cannot proceed, or we cannot move forward. Then if the only alternative is violence, we will use violence.”

That alternative of violence was one that Mandela used sparingly. Under Mandela, MK only carried out sabotage strikes on state infrastructure and military installations, going to great lengths to prevent civilian loss of life.

A decade after his passing, Israel’s bombardment of Gaza is killing thousands of civilians. The death toll is close to 16,000 Palestinians, including more than 6,000 children. To Mandela, it would surely have felt personal. As he said during his 1999 visit to Gaza, he felt “at home among compatriots”.

Mandela’s is one of the 12 remarkable lives covered in Dall’s recent book Legends: People Who Changed South Africa for the Better, co-written with Matthew Blackman.