‘Heroes to all of us’: Ukraine’s energy repair crews

As Russia targets Ukrainian energy facilities, repair teams race off to patch up the power grid when the strikes hit.

Kyiv, Ukraine – Vitalii, a 44-year-old Ukrainian electrical engineer with a neatly trimmed goatee and a penchant for clever jokes, recalls the terrifying moment he and five colleagues recently came under attack in the region of Donetsk in eastern Ukraine.

They had finished a long day repairing damaged electricity lines along one of the region’s pockmarked and war-worn roads when they moved into an open field to hoist up a repaired electricity pole. It had barely been lodged into place before they heard the familiar crack of incoming Russian mortars that began to pummel the earth around them. They quickly realised that Russian troops must have seen the pole appear above the tree line and had unleashed a volley of shells in their direction.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUkraine’s military chief warns of deteriorating situation on frontline

Two Russian journalists arrested over alleged work for Navalny group

Russia and Ukraine target each other’s energy sectors

With no buildings around where they could take cover, Vitalii remembers how they had to “crawl like crabs” through the field before huddling together behind their van. Shrapnel rained down on the vehicle until the shelling eventually subsided. The vehicle was badly damaged but, fortunately, the engine still kicked into action after they had clambered inside and they were able to speed away to safety.

He says the incident left them all in a state of shock, and they sat in silence back at their headquarters for a couple of hours before returning to work.

As the head of operations for DTEK, Ukraine’s largest private energy provider, in the Ukrainian-controlled parts of the Donetsk region, Vitalii, who requested that only his first name be given, has experienced what he describes as a “wartime environment” since 2014. That year, Russian-backed separatists captured swathes of the region, including the city of Donetsk, which had been Ukraine’s fifth largest. The heavy fighting in 2014 and 2015 damaged much of the region’s power infrastructure.

Since Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, energy facilities in the region have come under relentless attacks – forcing the 30 teams of energy workers Vitalii manages to carry out five to 10 repairs daily to damaged infrastructure. DTEK carries out most of the repairs in the Donetsk region.

Vitalii and his colleagues are overworked and face constant danger. Although he will not allow his workers to enter an area that he deems to carry a clear threat, the reality is that every repair job comes with the risk of being caught in a Russian drone, mortar or missile strike. Since the war began, 141 DTEK employees have died in the field nationwide.

It is exhausting and emotionally draining work, but Vitalii says the workers cope knowing they are providing a critical wartime service, particularly in the freezing winter months when the attacks on the energy infrastructure caused millions to lose heating. “Without electricity, there will be no water and no heating, so electricity is the essential resource for the region.”

You need humour to survive

Vitalii exudes an air of calm as he speaks over a video call from a control room in a secret location. His body armour lies at the ready behind him. His broad shoulders are hunched as he leans forward, his short brown hair flattened from wearing a hard hat. On technical matters, he expresses himself with a precision grounded in an engineering and academic background.

However, when it comes to the workers he manages daily, he switches to a softer, warmer tone, often breaking into a wry smile as he recalls moments of camaraderie formed under stressful situations. “Without a sense of humour, you wouldn’t survive,” he says matter-of-factly.

“It is a human reflex to respond to fear with laughter,” he explains as he recalls recently being called out to repair damaged energy lines near his old university that a missile strike had destroyed. As they looked out over the charred remains of the building, he turned to his colleagues and said, “I tried to ruin this place for five years, and now look, it took only one missile!”

Vitalii says that enduring the relentless stress of war and the responsibility of ensuring a “vital resource” is provided to the community in their region has created an unshakable bond between all the workers. “War unites,” he says firmly, adding they are now a “big family that supports each other”. For example, when a worker’s home is destroyed in shelling, they will band together, arrange new accommodation, and chip in to cover essentials.

The energy front line

In the early months of the full-scale invasion, Russia captured a number of power plants as the army occupied territory in the south and east of the country, including the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, syphoning off a segment of Ukraine’s energy production capability.

However, on October 10, 2022, Russia ushered in a new phase of the war, firing 84 missiles and 24 drones, the largest air strikes since the start of the war, many of which specifically targeted power plants and energy distribution systems.

Antonina Antosha, a press secretary at DTEK Group, says that if Ukraine were fighting “a military front line” on February 24th, on October 10th, they were also fighting an “energy front line”.

Since this date, Russia has regularly attacked Ukraine’s energy production facilities with cruise missiles and drones, targeting thermal and hydropower plants as well as the electrical grid that channels and distributes power across the country to consumers.

In an upscale café in a trendy Kyiv neighbourhood, Mariia Tsaturian, a spokesperson for Ukrenergo, the national electricity transmission company, shares her firm belief that Russia’s objective is “a total blackout of Ukraine”.

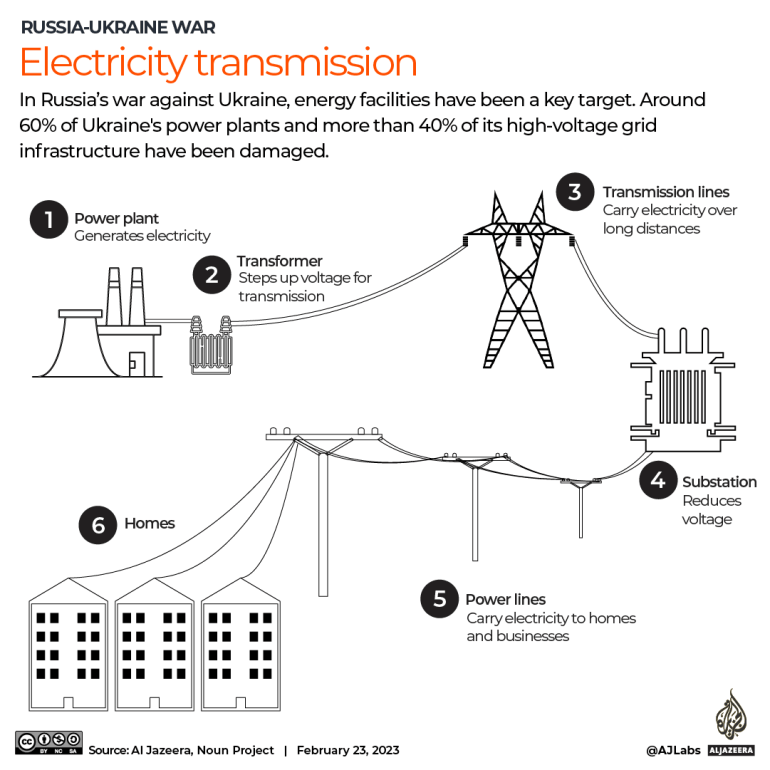

Above her is an array of bright low-hanging bulbs, and the café is full of young professionals hammering away on their laptops. It’s been a few days since Ukraine’s capital was hit by scheduled rolling blackouts that left parts of Kyiv in total darkness at any given time. With around 60 percent of Ukraine’s power plants and more than 40 percent of the high voltage grid infrastructure damaged, according to Tsaturian, these blackouts were designed by operators such as DTEK to distribute the available energy to all households equally.

“It is not the lack of light that is the big problem, as you can always use candles, but it’s the fact you have no water or heating in winter, no mobile connection, no logistics,” Tsaturian explains. She pauses as she looks out at a busy street scene outside the window. A truck has arrived to tow an expensive sports car, causing some commotion. “All civilisation is built on electricity,” she adds.

‘They know exactly where to strike’

Until February 24, 2022, the Ukrainian electricity grid had been interconnected with the Russian and Belarussian grids. The Russian energy sector’s intimate knowledge of the Ukrainian grid is why Tsaturian believes Russia has targeted specific areas of Ukrenergo’s substations – where electrical voltage sent by power plants can be reduced before being sent to operators such as DTEK – with such precision.

She pulls up a picture on her phone of a nondescript substation in a sun-beaten area of Ukraine. She zooms in several times and points to an autotransformer, a costly and crucial component in the electrical transmission process. It’s barely a speck in the sprawling machinery network, but Russian missiles frequently destroy such equipment. “We know Russian engineers are behind this because only they know exactly where to strike,” she says adamantly.

Since 2017, Ukraine had been in the process of joining the European electrical grid.

On midnight February 24, 2022, Ukraine had disconnected from the Russian grid as part of a three-day scheduled test – required by the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity – to prove the country could operate autonomously. With no support from the Russian grid and not yet connected to the European one, Ukraine’s energy system was isolated for the first time since its independence in 1991. Just four hours later, Russia launched its full-scale invasion.

“During these three days, we were weak. We helped them to choose the date,” she says.

After the invasion was under way, Ukraine’s electrical engineers worked day and night to synchronise with the European system. As a result, what had meant to be a year-and-half-long project was completed in about three weeks.

Tsaturian admits she was concerned by the frequency of the attacks on the Ukrainian energy infrastructure that required rolling blackouts between the end of October 2022 and the beginning of February 2023, which she estimates left around 12 million people cut off from the grid every hour.

The air defence systems, which had not been primed for Russia’s new tactics, left the open-air substations and large power plants vulnerable.

The frequency and violence of the strikes also left the workers traumatised and demoralised. At Ukrenergo, more than 1,500 employees are working in the field at any one time. During October and November 2022, there were weekly strikes on energy facilities, and from December onwards, the attacks came every two weeks. Tsaturian uses the example of a substation near Kyiv – one that is crucial for the transmission of energy from the west to the east of the country, and that she says has been targeted 24 times by missiles since October 10 and hit directly nine times. “Imagine working there!” Tsaturian says with an exasperated tone. “A week after your repair it, a missile strikes the same place. The workers were feeling desperate and thinking, ‘Why are we doing a suicidal job?’”

Power returns to Ukraine

In recent weeks there has been a tangible improvement in the energy supply to Ukraine’s major cities, with rows of privately owned diesel-run generators that line the streets in case of blackouts now standing idle. Tsaturian estimates that at present, there are around 200,000 Ukrainians living in non-occupied territories who are subjected to the scheduled energy blackouts.

She says that this change is partly down to the vast improvement in the country’s air defence systems in protecting critical infrastructure and the ability of everyone out in the field to work “faster and more creatively”.

“We have learned a lot technically,” she says, highlighting the ability to replace a 250-tonne autotransformer in a few weeks rather than the one and half months it took during peacetime. “You have to be very creative, especially when you are restoring the grid near the front line in the open air,” she says.

It is a point echoed by Vitalii. “Before the full-scale invasion, a team would get an assignment, collect the materials, plan and move forward with the execution of the assignment,” he explains.

Now he says a team will be told there has been damage at a general location but will be given no further information. They will then head into the unknown. On arrival, they can often find fires still ablaze at the location. If he deems anything too dangerous or uncertain, Vitalii will order his workers to wait at a safe distance until a full assessment has been made. “The scariest for me is when I cannot control the situation,” he admits.

The danger also leaves no margin for error. Each decision must be ruthlessly efficient and executed at breakneck speed. Despite the lack of available time, the team must pack and carry all materials as they won’t know what they need.

But the recent supply improvements have led to a huge boost in morale, according to Tsaturian. “I see now the workers feel they are on a real mission. They see the lights on everywhere – they see the result of this hard work,” she says.

‘Heroes’ and blackout hacks

The efforts of the energy workers are celebrated among the Ukrainian public.

Jeanna Prokhorenko, the 36-year-old owner of Zerno, a cafe located in a prefabricated housing container along the Dnieper River that runs through Kyiv, is thankful that her business no longer needs to rely on a gas-guzzling generator. “I am proud of everyone who helps restore the electricity grid,” she says with enthusiasm. “I feel a strong emotional connection with every one of them.”

It’s a sentiment echoed throughout the Ukrainian capital. At a beauty salon on the ground floor of an imposing beige apartment block, 42-year-old owner Inna Hartman describes the energy workers as “heroes to all of us”. The salon is now doing a roaring business with a series of stone-faced middle-aged men receiving similar buzz cuts.

The recent stable electricity supply has helped Hartman keep her business afloat, as she could not afford a generator and would have to close the store during power outages that she says could last around eight hours.

According to Prokhorenko, the cafe owner, local business communities have also grown closer during the outages. For example, the florist next door to the cafe was connected to a different DTEK district, which often resulted in one of the businesses being without electricity while the other had it. “The neighbours would often come over with a power cable for us and vice versa,” she says. “We would also end up talking, which made our friendships stronger, and we felt more united.”

It is not just energy workers who are going the extra mile, but local communities are also rallying together and coming to the aid of people left vulnerable by the blackouts. During one unexpected outage, Prokhorenko’s 10-year-old daughter Dominika was stuck for more than an hour in their apartment block’s rickety lift. “It was very scary at first, but I had a torch, and then the neighbours came out and talked to me through the doors, which calmed me,” Dominika recalls. “They finally grabbed some tools and rammed open the door.”

Prokhorenko has lost count of how often neighbours became stuck in the lift, but she says you could always rely on passersby to lend a hand. “We all have a new skill of opening lift doors!” she jokes.

Nearby, Yulia Krugliak, the 26-year-old manager of a tea house, says that her establishment was the only place with a generator during the initial blackouts for a two-kilometre (1.2 mile) radius. So she opened the premises to the public, allowing people to come and charge their devices. She would even regularly host a mother who needed electricity to connect emergency medical equipment for her daughter with an acute respiratory condition.

The months of outages have also left many Ukrainians with a stockpile of inexpensive creative solutions to electrical shortages.

In a rustic split-level artist studio in central Kyiv, Nick Ivanov, a 30-year-old location manager for a film company, shuffles through a series of torches he uses to light his home during blackouts, to reveal a set of makeshift devices wrapped in black electrical tape. He calls these devices “endless candles” and says they have become popular nationwide. He pulls back the tape to reveal a battery from a disposable vape pen connected to a pea-sized diode. The battery, he says, can be recharged, and the light can effectively be used forever.

‘We have won the battle but not the war’

Tsaturian of Ukrenergo is relieved and proud that energy workers have restored much of the country’s electricity supply.

Stanislav Kovalevsky, Ukraine’s former deputy minister of energy, says the “rapid pace” with which the country has regained its energy supply is thanks to the “exceptional unity of our people”, the energy workers, air defence forces and the support of Western partners.

Tsaturian says that since January 2023, Ukraine and Moldova – which has also faced outages caused by Russian strikes on Ukrainian infrastructure – can import energy from Slovakia, adding a modest but crucial layer of security. The warmer, brighter upcoming months between April and October will also bring respite to some energy-related issues.

However, she warns against complacency. “We have won the battle but not the war,” she says sternly.

The energy sector in Ukraine still faces a host of issues, including a dwindling stock of autotransformers, which workers are often forced to move between substations. In addition, replacement orders from other countries can take months, and unlike other machinery parts, autotransformers can not be buried underground, as they need outside air to remain cool.

Tsaturian also says that repairing equipment is not the same as replacing it. “It is like a car. When you crash it and repair it, you can’t guarantee it will drive perfectly again,” she explains.

The upcoming months, she says, will be used to help build up reserve stocks and prepare defensive arrangements for the substations. However, she admits that not everything can be protected.

“We know winter will come, and Russia will repeat these attacks,” she adds. “In the future, we have to be well prepared.”

Tsaturian says the energy companies have also had to contend with misinformation campaigns from Russia that aim to plant seeds of discontent among the Ukrainian public, saying, for instance, that Ukraine is “secretly exporting energy despite shortages at home, or that energy companies are exaggerating the extent of the damage”.

‘We work non-stop’

A year since the full-scale invasion began, Ukraine’s energy workers have had little rest.

“We are all exhausted, from the CEO [of Ukrenergo] to the teams in the field; it takes all your time, all your life, you have no work-life balance, but it is our mission, and we are devoted to this now,” Tsaturian says.

Vitalii says that although he does not go out in the field during the weekends, he is in constant contact with his teams, and every morning, they have a call about what needs to be addressed.

He has adult children who do not live in the Donetsk region. His wife, however, also works in the energy sector, so they leave together for work every morning. Whoever returns home first cooks dinner, which he says he often does, joking that as well as being great at his job – he is also a great cook.

“We work non-stop 24-7,” he says candidly. They will not rest, he adds, until “Ukraine achieves victory in the war”.