Greece boat tragedy: What do we know about the coastguard’s role?

The European Commission calls for ‘thorough and transparent investigation’ into the deadly sinking of a boat off Greece.

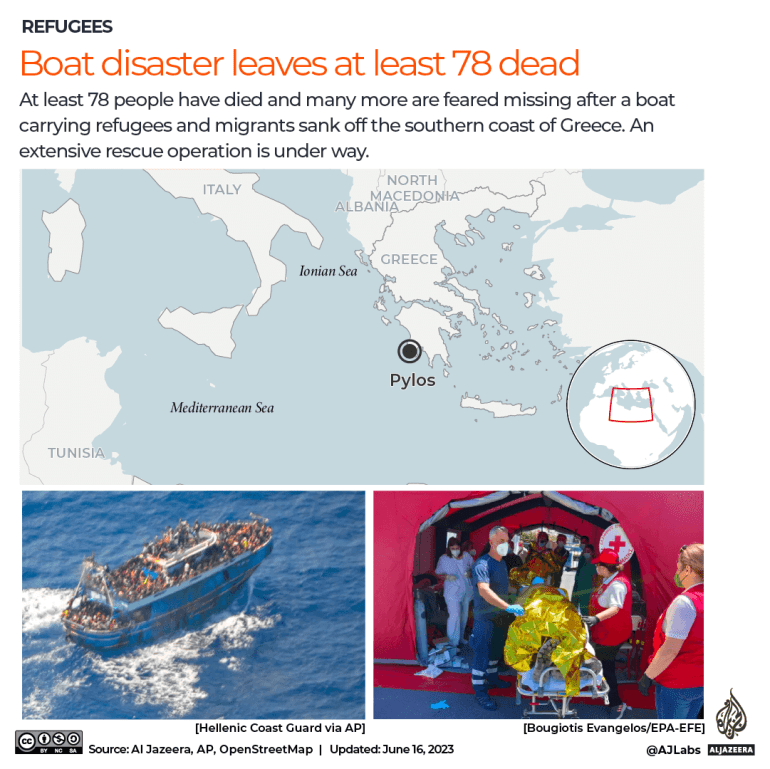

Athens, Greece – Hundreds of people remain missing in the aftermath of a shipwreck off the coast of western Greece, near the town of Pylos in the early hours of June 14.

So far, only 104 survivors have been found, none of them the women or children who were allegedly kept in the hold of the ship.

Keep reading

list of 3 items‘Heinous crime’: Pakistan makes arrests after Greece boat tragedy

Mourning in Pakistan as hundreds die in Greece boat tragedy

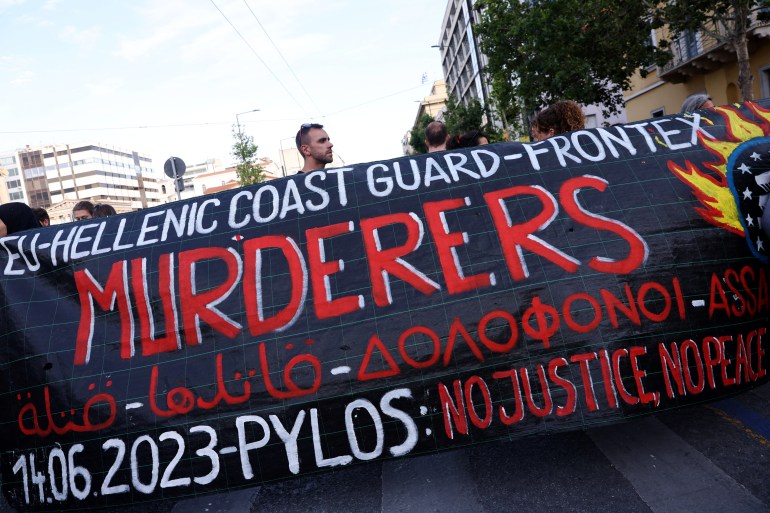

Questions remain over the role of the Greek coastguard in the incident and why those onboard were not rescued sooner.

Alarm Phone, a hotline for refugees in distress in the Mediterranean, said it had alerted Greek authorities at 5:53pm local time (14:53 GMT) after it had been contacted by those onboard for help.

Media investigations have also suggested the boat was barely moving in the seven hours before it capsized, in contradiction to claims by the Greek coastguard that the boat was on course to Italy and had rejected rescue.

The coastguard has also been forced to reject allegations that the boat was towed, contradicting testimony from a number of survivors, although it has admitted a rope was briefly attached to the ship which later sank.

The UN has welcomed an independent probe into the sinking while the European Commission stated that any investigation should be “thorough and transparent”.

This is in contrast to the position expressed by the Greek Supreme Court prosecutor Isidoros Dogiakos, who has urged absolute secrecy in the investigation.

Dr Nora Markard, professor of international public law and international human rights at the University of Munster, told Al Jazeera that it was “really important to centre the obligations of the Greek state” in the questions of accountability.

“They were on the scene, they were in their own search and rescue zone, they failed to rescue and they failed to coordinate a rescue. And then they actively put the lives of the people on the boat at risk,” she said.

“Distress is also an objective situation,” Markard said in response to claims those onboard had initially rejected a rescue.

“A boat is in distress when it is when it cannot safely reach its destination, for example because it overcrowded – whether or not the captain claims that is fine,” she said.

“The duty to rescue is triggered when a boat is in distress, and you’re nearby or you’re informed of the situation, and it only ends once another boat has taken on the rescue. Until then, all the ships nearby are under an obligation to rescue,” she said.

“People need to be brought to court, there needs to be accountability for what happens at sea, we cannot have these cases again and again, and then nothing happens,” added Markard, pointing to a history of documented human rights abuses at the Greek border.

“This is a rule of law problem because this is a systematic failure to rescue, the systematic non-application of the law of the sea and human rights obligations,” she said.

“At this sort of level, this is not an isolated incident. This is a policy, and so we have a massive rule of law problem with Greece at the border.”

Omer Shatz, an international lawyer and legal director of front-LEX, a legal hub challenging EU migration policies in European and international courts, told Al Jazeera it was clear Greece should have immediately performed a rescue.

“Under maritime law, Greece was obliged to launch an urgent search and rescue operation, twice: first as the coastal state responsible for the search and rescue zone in which the boat was located, and second as the flag state whose vessels were for so many precious hours accompanying on-scene and interacting with a vessel in distress,” he said.

“No less than three maritime conventions obligate Greece to render immediate assistance in this state of affairs,” he added.

Shatz said the likelihood of Greece being taken to court under failure to uphold maritime law is, however, slim.

“The problem with maritime law is that only states, not individuals, can take Greece to court and given the complicity of the 27 members of the EU in this policy this is unlikely in this case”, he said, but pointed out another legal avenue in which Greece may be held accountable.

The only other path would be to take a case to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), he said.

“Last July, the ECHR ruled in the Safi case, where the Greek coastguard unsuccessfully tried to tow a refugee boat to Turkish waters and as a result the boat capsized and many children and women perished,” Shatz said.

“In the present case, the many hours between the time Greece had become aware of the risk and failed to act, if not acted in a manner that actively risked the vessel is not in dispute,” he said.

“Hence, it is fairly straightforward that the court will once again determine that Greece breached its obligation to protect the right to life of persons under its effective control, be it territorially or extraterritorially.”

Dimitris Choulis, a lawyer based in the Greek island of Samos, pointed out that the area of the wreck had previously been a known site of towing and pushback previously, but said it was impossible to say what the coastguard’s intention had been.

“We can only touch what happened and what happened is that they failed to rescue them, even though they had the opportunity and the responsibility,” he said.

Responsibility of Frontex

Shatz added that the EU’s border security agency Frontex also had questions to answer about its role – or lack thereof – in the rescue operation, given the boat had been spotted on Tuesday morning before it sank by an aerial asset of the agency.

“At the end of the day the case is not about maritime rescue but the criminal persecution of a singled-out population,” he said.

“It comes down to one question: if those on board weren’t refugees but white Europeans, would Frontex and Greece have accompanied them to their death instead of rescuing them?”