Against every instinct:

How doctors in Gaza persevere amid Israel attacks

“No doctor wakes up in the morning and says: ‘I'm going to amputate a child's leg without anaesthesia.’

“You don't want to watch children suffer,” Dr Amber Alayyan with Doctors Without Borders, known by its French initials MSF, tells Al Jazeera.

The measured cadences of the voice of the charity’s deputy programme manager for Palestine suggests just how inconceivable it is for her, as a doctor and a mother, to cause pain to a patient and to a child.

Yet it is the moral conflict her colleagues in Gaza face daily, minute by minute, as they try to treat unprecedented numbers of injured people flooding into the Gaza Strip’s barely functioning hospitals.

Your natural instinct is to take care of people… to protect people. ... You've been trained over and over and over and over for years.

As doctors in Gaza are forced to make split-second decisions on who to save and who to let die, on whose pain to relieve and whose they do not have time to, it is that innate instinct and their Hippocratic oath that is assailed by decisions they never thought they’d have to make.

Burdened with personal losses and struggling to operate under unrelenting Israeli bombardments, this is the story of how medical workers are fighting to keep Gaza’s healthcare system going.

How Gaza’s healthcare system has been destroyed

It is nearing midnight in Gaza and Mohamed S Ziara, a Palestinian doctor, is on a WhatsApp call to Al Jazeera. His tone is soft and unaffected by the rumbling explosions and pop of gunfire that can be heard in the background.

The plastic surgeon is working 12- to 14-hour shifts, six days a week at the European Gaza Hospital (EGH) in Khan Younis, where he treats up to 15 cases a day.

Ziara describes the healthcare situation as “catastrophic”.

“It doesn’t match anything I’ve seen before, even with previous escalations and war,” says Ziara, who has worked during Israel’s assaults on Gaza since 2014.

He has been posting about Israeli attacks near the EGH and the conditions inside on his Instagram account.

The widespread damage caused by Israeli attacks since October 7, following Hamas’s surprise attacks on Israel, has led to a shortage of medical staff and supplies and an urgent need for fuel, electricity and water.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), only 15 of Gaza’s 36 hospitals are partially functional - nine in the south and six in the north.

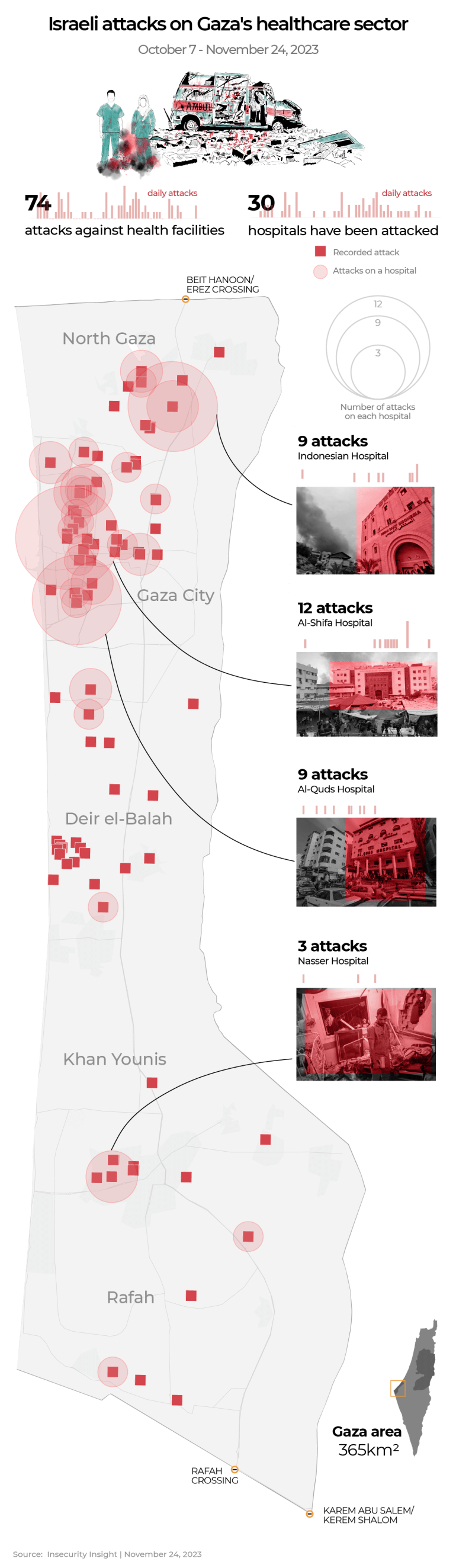

From October 7 to November 24, there were 74 Israeli assaults on health facilities with 30 hospitals attacked in Gaza, according to Insecurity Insight, a humanitarian association that collates data on threats facing people in dangerous environments.

Northern Gaza, including Gaza City, has borne the brunt of attacks on the healthcare sector, but as the war has progressed, previously designated safe areas south of Wadi Gaza have come under Israeli fire.

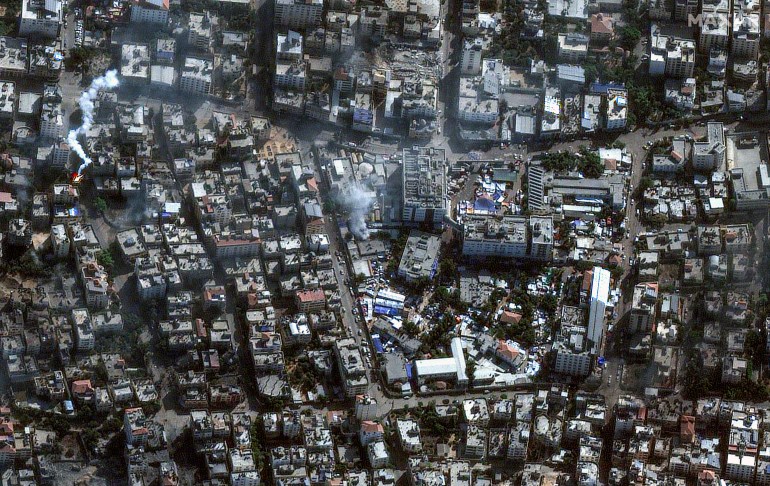

The map below summarises the Israeli attacks on Gaza’s healthcare sector during the first seven weeks of the war.

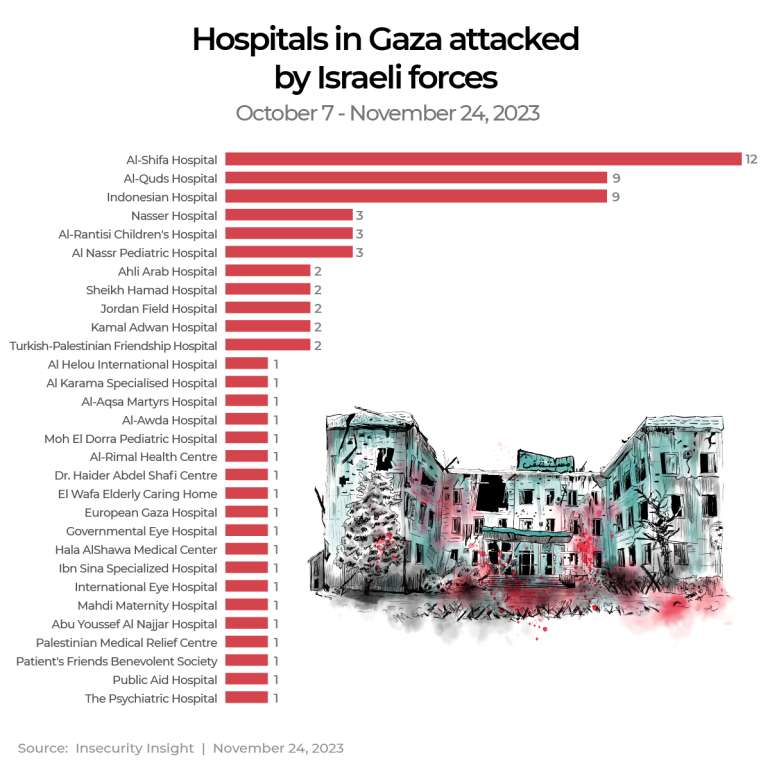

The hospitals that have been attacked most often include:

- al-Shifa Hospital - attacked 12 times

- al-Quds Hospital - attacked nine times

- Indonesian Hospital - attacked nine times

- Nasser Hospital - attacked three times

Insecurity Insight documented at least 26 other hospitals from across the Gaza Strip that were attacked by Israeli forces over the same period.

These repeated attacks came during an Israeli order on October 13 that instructed all 22 hospitals in northern Gaza to evacuate to the south within 24 hours. The WHO described the order as “impossible to carry out” and “a death sentence for the sick and injured”.

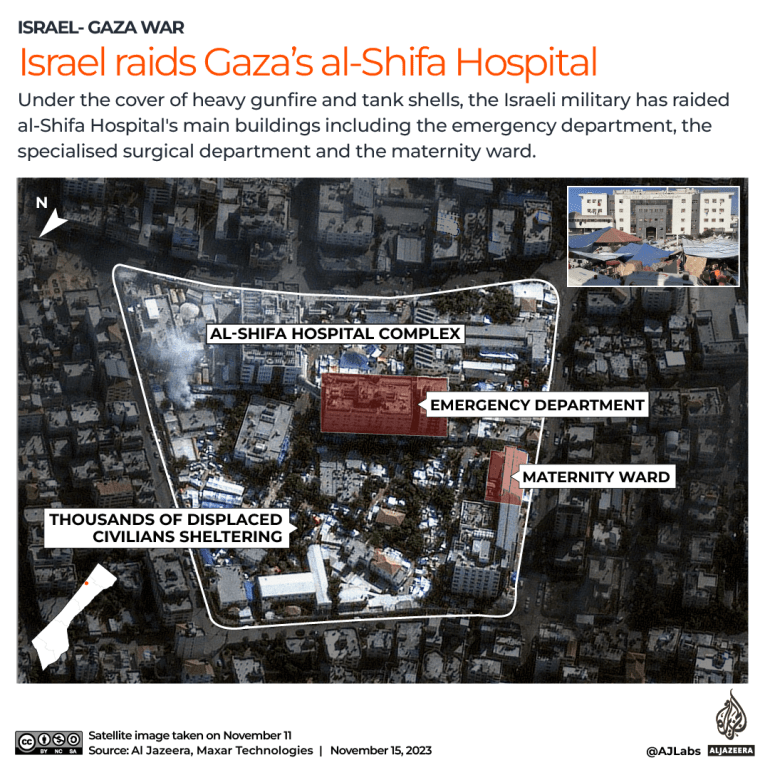

Israel’s raid on al-Shifa Hospital

One of the first hospitals to come under fire was al-Shifa Hospital, Gaza’s largest medical facility, located in the Remal neighbourhood in Gaza City, where Ziara worked before EGH.

“I remember that I was watching TV, and the spokesman of the [Israeli] army was asked twice about the possibility of bombing the hospital, and he replied that everything is possible,” Ziara says.

Israeli soldiers flanked al-Shifa Hospital on three sides on November 15 and then stormed the complex after Israeli accusations that it was serving as a Hamas command centre.

“We have never seen any military action or military activity inside the hospital,” Ziara says, adding that he thought the threat to the hospital was merely propaganda from the Israeli army. “We never thought that they would reach the hospital and that we’d evacuate patients and the injured.”

Several doctors, including Norwegian Mads Gilbert, who has worked in Gaza for several years, have said they had not seen any evidence of military activity at the hospital during the war.

After the storming of al-Shifa Hospital, a number of United Nations missions were carried out in cooperation with the Palestine Red Crescent Society (PRCS) to evacuate patients and healthcare workers.

The same exercise has been attempted more recently at hospitals in Deir el-Balah in central Gaza and Khan Younis in the south - namely Al-Aqsa, Nasser and EGH - due to ongoing hostilities nearby.

Ziara says he witnessed drone attacks on al-Shifa Hospital.

“They were shooting at people. They injured many. They shot a missile at the hospital garden and killed about four people staying there who had evacuated or were refugees,” he says.

Healthcare attacks and 'war crimes'

Assaults such as those seen on al-Shifa Hospital have raised questions about the legality of attacks on healthcare facilities. International humanitarian law, based on the Geneva Conventions, stipulates that hospitals are considered “civilian objects” and receive de facto protection. Despite that prohibition, Israel has continued to target healthcare structures and workers.

“The UN has been very clear that hospitals, civilians and healthcare workers should be protected, and we continue to call for their protection. They're not a target,” Dominic Allen, the UN Population Fund's representative for Palestine, tells Al Jazeera.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has said attacks on healthcare are “attacks on the sick and the injured”, which need to be "investigated as a war crime”, according to A Kayum Ahmed, special adviser on the right to health at HRW.

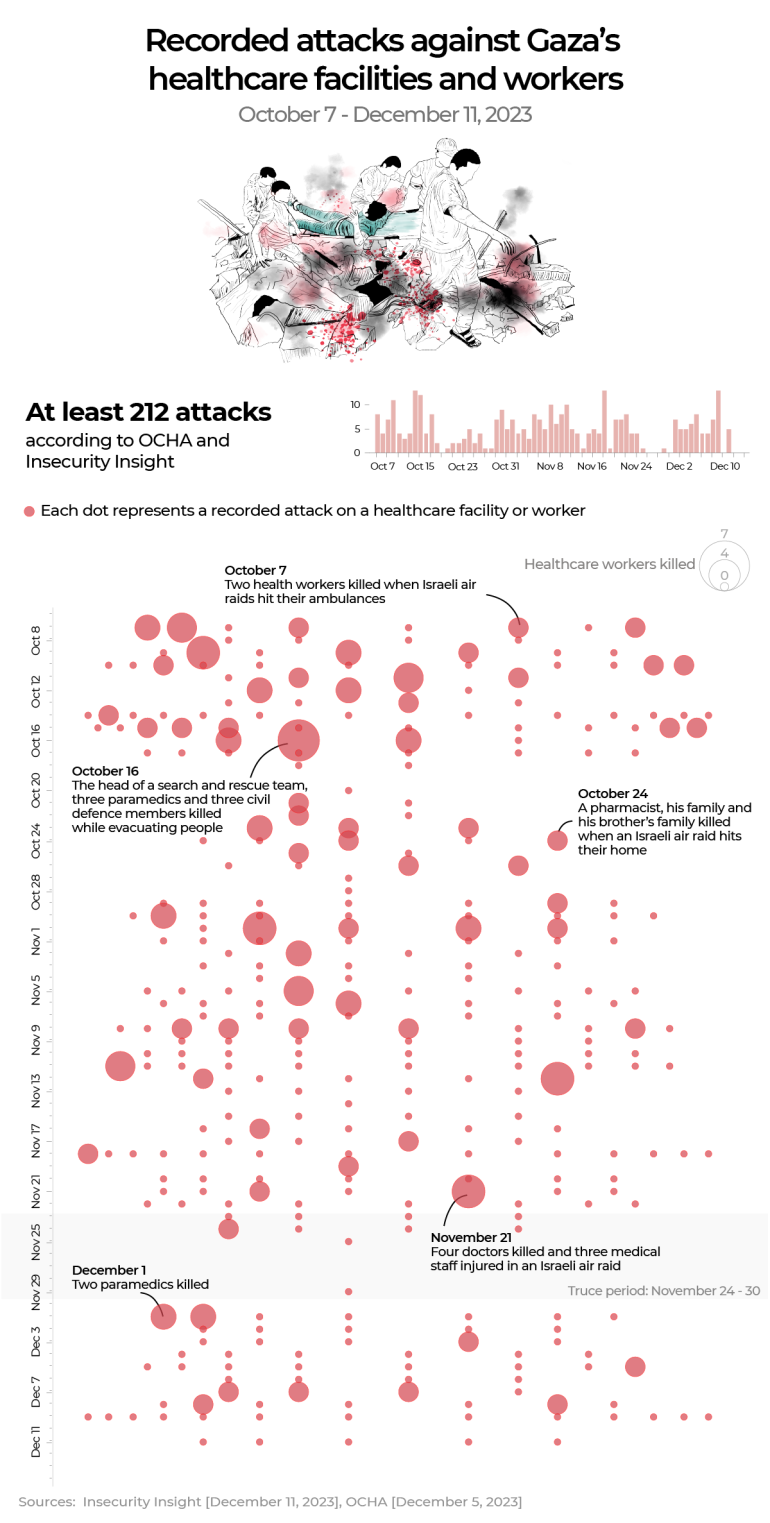

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and Insecurity Insights, there were at least 212 attacks on healthcare facilities and workers from October 7 to December 11.

The graphic below shows a timeline of all recorded incidents during those nine weeks. Each dot represents a recorded incident and is sized according to the number of casualties.