In Pictures

God of Sight: Prominent Nepal doctor to expand work beyond border

Dr Sanduk Ruit has performed some 130,000 cataract surgeries and is now aiming to take his work to other nations through a foundation.

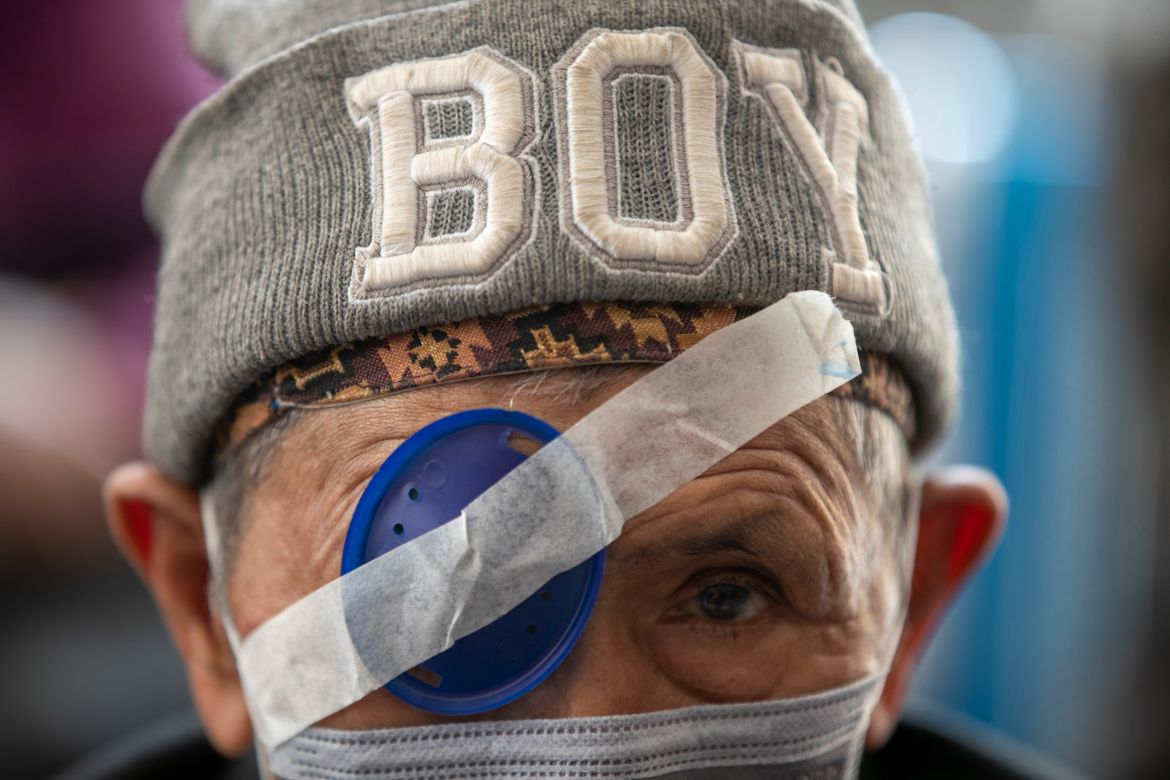

Just next to Nepal’s Mayadevi temple where Buddha was born more than 2,600 years ago, hundreds of people line up outside a makeshift hospital on a recent hazy day, hoping their fading eyesight can be restored.

A day later, the saffron-robed Buddhist monks, old farmers and housewives are able to see the world again because the nation’s renowned eye surgeon Dr Sanduk Ruit was there with his innovative and inexpensive cataract surgery that has earned him many awards.

At the visitor centre turned into temporary eye hospital in Lumbini, located 288 kilometres (180 miles) southwest of Nepal’s capital Kathmandu, the assembly-line surgery has made it possible for nearly 400 patients to get Ruit’s surgery in just three days.

“The whole objective, aim and my passion and love is to see there remain no people with unnecessary blindness in this part of the world,” said Ruit, also known as Nepal’s “God of Sight”.

“It is important that the people do receive equitable service and not that haves receive and have-nots don’t receive it. I want to make sure that everybody receives it.”

Many people in Nepal, most of them poor, have benefitted from Ruit’s Tilganga Institute of Ophthalmology in Kathmandu. He regularly visits remote villages high in the mountains and lowlands of the Himalayan nation, taking with him a team of experts and equipment bringing surgery to their villages.

Ruit has already performed about130,000 cataract surgeries and is now aiming to expand his work, taking it to as many countries as possible through a foundation he has formed with a British philanthropist Tej Kohli which is aiming to complete 500,000 surgeries in the next five years.

Ruit said the idea of the Tej Kohli Ruit Foundation is to make cataract surgeries in Nepal affordable and accessible to all.

“We will scale it up globally to other parts of the world where it is needed,” he said.

Ruit began his work in 1984 when the surgery was done by removing the entire cloudy cataract and giving thick glasses. He found that most people would not wear these glasses and chances of complication were very high.

So he pioneered a simple technique where he removes the cataract without stitches through small incisions and replaces them with a low-cost artificial lens.

Ruit’s average surgery costs about $100. It is free for those who cannot afford it. Patients rarely have to spend the night at the hospital.

Nepal has a limited number of hospitals and health workers, and services are out of reach for most people.

Cataracts, which form a white film that cloud the eye’s natural lens, commonly occur in older people but also sometimes affect children or young adults. The condition first causes vision to blur or become foggy because the eye is unable to focus properly.

As the cataract grows and matures, it can eventually block out all light. Exposure to harsh ultraviolet radiation, especially at high altitudes as in Nepal, is a huge risk factor.

At the surgery camps in Lumbini, patients and family were all praise for the doctor.

Bhola Chai, a 58-year-old office worker, who had to retire because of his fading vision, was thrilled he could finally see again. “This surgery has changed my life,” he said.

Others who have already benefitted from Ruit’s cataract surgery likened him to a god.

“The doctor is just not god-sent but he is a god for me who has given me a new life,” said Satindra Nath Tripathi, a farmer who benefitted from the surgery. “My world was completely dark but now I have new life and new sight.”