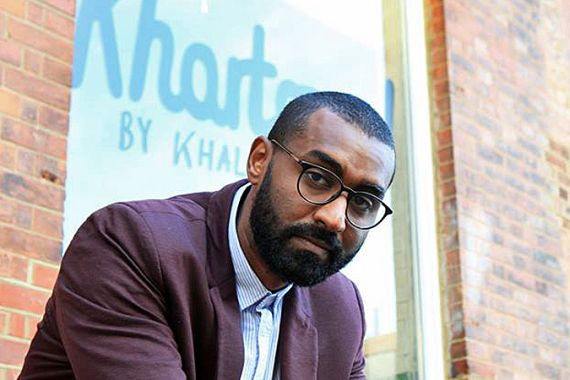

Q and A: Khalid Albaih talks ‘Khartoons’

Sudanese cartoonist Khalid Albaih reflects on the power of images to create dialogue about the Arab world.

Inspired by the late Palestinian artist Naji al-Ali, renowned for criticising Arab governments and the Israeli occupation, Romanian-born, Sudanese cartoonist Khalid Albaih has chosen to fight back with his satirical series, “Khartoon!”

Struggling to find work in traditional media, he took his work online and it went viral. During the Arab Spring, he discovered that his work was being painted on walls from Tahrir Square to Beirut; Albaih’s Khartoons have since been shown at exhibitions around the world.

Albaih, who currently lives in Doha, spoke to Al Jazeera about how he came to draw and how he hopes his cartoons will create a dialogue about the Arab world that transcends language and culture.

Al Jazeera: Where does your interest in politics come from?

Khalid Albaih: I come from a very diverse political family. My dad was a diplomat; my uncle Abdel Rahman Suwar al-Dahab was the president of Sudan; another uncle Babiker al-Nur, who was in the Free Officers Progressive group, was killed by Nimieri along with the head of the Communist party, after an attempted coup. I grew up with these political conversations going on all the time.

AJ: Why drawing and not writing?

KA: I started drawing really early on, doing my own comic strips in school, but politically it was during university. We had a Sudanese union [and] I was making fun of everyone and I thought, I can make this a career. My father used to bring home these Egyptian, cartoon-based magazines, such as Sabah Al Khair and Rose al-Yusuf, when I was a kid.

They were very educational for me and for my friends growing up. So I thought it was very close to the public – you don’t have to be educated or specialised [to understand] – it’s a cartoon about what’s going on. So for me it was the perfect art form.

AJ: Do you think images can be more powerful than words?

KA: A lot of the problems are with the “clash of civilisations”; we have our own media and the West has theirs. They have no idea about what’s going on over here, and this was always the problem, this miscommunication.

So when you have a drawing that can be understood by a Republican in the US, or a far-right guy in Holland, and a Muslim critic from Saudi, everybody understands the same message and people get closer.

AJ: Do you ever self-censor?

KA: Living in this part of the world, you always have to censor yourself. This is the conversation that always comes up, whenever I’m at conferences or exhibitions in the West. They always talk about two things – the Prophet Muhammad cartoons and why I don’t mention Qatar.

Being a cartoonist from this part of the world is harder, but it definitely makes us more creative. Yes, we don’t have the freedom and something might happen to you of course, but this is how we are. The self-censorship is part of the religion, part of the culture.

AJ: By the very nature of your cartoons, have you even gotten into trouble with the authorities?

KA: At the beginning, I used to get really nervous and thought, “Oh there’s going to be trouble.” My Instagram and my Facebook accounts got hacked, and I assume they were Syrians because the cartoons were about Syria that day. But I get all sorts of messages. Islamists call me a Liberal, Israel-lover or whatever, and Israelis call me an anti-Semite, so over time you just get used to it.

And this is the nice thing about social media, it starts a conversation between people who never spoke before. I don’t publish in any old media, but mainly online. I have space to do what I want, I don’t have an editor and I don’t belong to any political party.

AJ: Did you try to use the traditional route?

KA: In 2009-10, I was going around Egypt, Sudan, even Doha, with some of my cartoons. I actually got kicked out of an editor’s office once. I think it was a turning point in my life. I went to his office after a week of trying to get in, and it was huge, with not even one computer in sight. [He was] sitting there smoking like it was 1983, and I showed him the cartoons and he wouldn’t take a second look at them.

He said: ‘These are not cartoons. You should be a graphic designer or something. They need bubbles, where are the bubbles?’ And he kept insisting on the bubbles. So that day, walking out of that office, I thought, I’m going to go online.

And coincidentally, that was exactly the same time that the Arab Spring happened and for the same reasons. People in power don’t listen to the youth. The only refuge that we had was the Internet, and it was at the same time, on the first day when [Mohamed] Bouazizi burned himself [in Tunisia] because of his anger. I did a cartoon about Tunisia that went viral [and] ended up on Wikipedia. My page, during the first three months of the Arab Spring, went from having 200 ‘Likes’ who were my friends on Facebook, to having around 60,000 people.

AJ: So do you feel a sense of responsibility to draw?

KA: I feel responsibility to remain faithful to my principles and not to be a propaganda machine for any media outlet or party.

The responsibility can be heavy. A lot of people in Sudan and here in Qatar expect me to say certain things, but this is my point of view.

AJ: How is your work received in Sudan?

KA: The government and pro-government people don’t like it. Which is good, it means I’m doing the right thing. It’s great, a lot of people use my work and share it on social media.

AJ: As someone who comments on movements in this region, where do things stand? Is the Arab world reaching a stalemate, or is it still in flux?

KA: We’ve always had somebody that placed themselves in power and would not move. We’re going through a really tough time. We’re like teenagers trying to find ourselves. We’re angry at our parents, we’re angry at ourselves, we turn goth and we look for religion. I think we’re just trying to find who we really are, and I think it’s normal.

The French Revolution took years and it was really bloody. We can’t have a revolution today and have everything be fine tomorrow. We have to go through stages and learn from mistakes.

AJ: And Sudan?

KA: In Sudan though,it’s totally different. People are very tired after 40 years of war. And that’s one reason for people questioning why the revolution did not succeed in Sudan, even though there were three attempts in the last three years. Many people got arrested and many people got killed by the government forces. I think the Arab Spring would have succeeded in all the Arab countries, with the dictators who have been there for 30-40 years if [Libya’s former President Muammar] Gaddafi didn’t stay as long and fight back. Because Gaddafi fought, then [Yemen’s former President Ali Abdullah] Saleh fought and [Syrian President Bashar al-] Assad is still here.

So now people are scared of the mess and chaos and this is what these guys are betting on. This is what [Sudanese President Omar] al-Bashir is saying all the time in Sudan, you know: ‘You want chaos, is that what you want? We’ll give you that. If I leave then what?’ But I think it’s going to happen; sooner or later it’s going to happen. It’s going to collapse.