Myanmar cracking down on opium, but conflicts push drug trade

UN report shows less land being used to grow opium poppies, but conflicts hampering eradication programme.

The amount of land being used to grow opium poppies continues to decline in Myanmar, but ongoing conflicts are hampering efforts to stamp out the trade at a time when the illicit drug economy is becoming increasingly diverse, according to a new United Nations report.

Some 37,300 hectares of land in the country was under poppy cultivation last year, down from 41,000 in 2017, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) said in its Myanmar Opium Survey 2018 on Friday.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat to know about Chinese Olympic swimmers’ doping scandal

West Africa’s Sahel becoming a drug trafficking corridor, UN warns

Behind India’s Manipur conflict: A tale of drugs, armed groups and politics

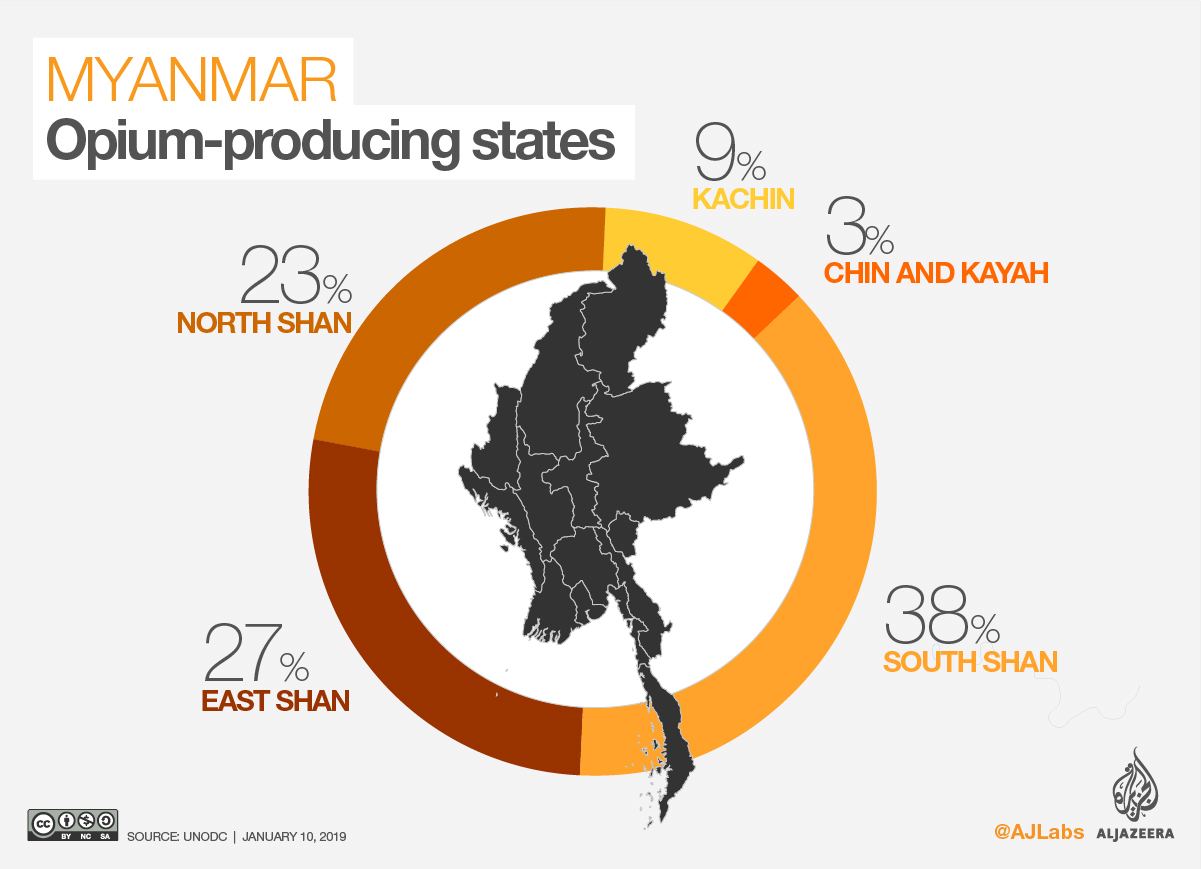

Nearly 90 percent of all the opium was grown in the northeastern Shan state, where government forces continue to battle ethnic rebels.

“The biggest drops in cultivation have been seen in areas that have had relatively good security,” the UNODC said.

“However, in parts of Shan and Kachin experiencing a protracted state of conflict, high concentrations of poppy cultivation have continued – a clear correlation between conflict and opium production.”

Myanmar has been battling conflicts in its border regions for decades and the unrest has long underpinned the drugs trade; in the mid-1990s, Golden Triangle, which includes the border areas of Laos and Thailand in addition to Myanmar, had the dubious distinction of being the centre of the world’s opium and heroin trade.

Since then, government eradication efforts have helped tackle the problem, but the conflicts continue to provide the kind of conditions that allow the illicit drug trade to thrive.

Myanmar is still the world’s second-biggest producer, after Afghanistan, and it remains the major supplier of opium and heroin in East and Southeast Asia, as well as Australia.

Shift to methamphetamines

The UN drugs and crimes agency said civil strife last year also made it difficult for the government to access opium-growing areas, obstructing efforts to destroy poppy fields.

About 2,605 hectares of cultivation was eradicated in 2018, 26 percent less than the previous year, it said. UNODC data shows eradication has been in decline since 2015.

The agency noted that economic problems, including a lack of job opportunities and income inequality, also contributed to the resilience of the drug trade amid increasing efforts by traffickers and organised criminals to diversify the market.

|

|

The UN drugs and crimes agency pointed out that of the 11 countries in the region that shared data with it, nine now say methamphetamine is their biggest drug of concern, compared with four decades ago when heroin was their main worry.

“There has been a sharp increase in the supply of, and demand for, synthetic drugs and particularly methamphetamine across East and Southeast Asia and neighbouring regions,” the UNODC said. “The downward trend in opium cultivation and related heroin production needs to be understood in this context.”

The agency’s report came days after the International Crisis Group said that the long-running conflict in Shan state had turned the area into a hub for the global trade in crystal methamphetamine or ice, with the business controlled by local armed groups.

“The trade, which now dwarfs legitimate business activities, creates a political economy inimical to peace and security,” the group said in a report on Monday.

“It generates revenue for armed groups of all stripes.”

Crisis Group also said the militias and other armed groups who control both the areas of production and the main trafficking routes have no incentive to demobilise, because the weapons, territorial control and absence of state institutions are essential to the maintenance of their drug income.

The trade also attracts transnational criminal groups and allows “a culture of payoffs and graft to flourish” as officials are bribed for protection, support or to turn a blind eye to what is happening.

This “adds to the grievances of ethnic minority communities that underpin the 70-year old civil war“, the group’s research found.

![Myanmar map of opium, and conflict [Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/0d40728c9f1146d9899c57575447e544_6.jpeg)

Regional strategy needed

In its survey, UNODC noted that while fewer hectares of land was being cultivated with poppies in Shan and Kachin, the concentration of fields was highest in the parts of the states where the conflict was most protracted.

In Kachin, most opium cultivation took place in areas controlled by the Kachin Independence Army, while in North Shan it was in areas under the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army; in South Shan, the Pa-O National Liberation Army, the Restoration Council of Shan State and the Shan State Army South, and in East Shan, the People Militia’s Force.

“There is a direct connection between drugs and conflict in the country, with the drug economy supporting the conflict and in-turn the conflict facilitating the drug economy,” the UNODC said. “Providing solutions to the conflict requires breaking this cycle.”

Resolving the issue will also require regional cooperation, Jeremy Douglas, regional representative for the UNODC in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, told Al Jazeera.

The manufacture of methamphetamines and ice require precursor chemicals, which are often smuggled into the country from China, while the drugs themselves need reliable trafficking networks to reach consumers beyond Myanmar’s borders.

“The region needs a shared strategy,” Douglas said. “Myanmar will not be able to solve the situation alone.”