Gaza’s Great March of Return protests explained

Here’s the backstory of the Great March of Return protests and the conditions that have brought Gaza to this point.

Every Friday for the past year, Palestinians in Gaza have protested along the fence separating the besieged strip from Israel.

They are demanding the right to return to their ancestors’ homes, which they were expelled from in 1948 when Zionist militias forcefully removed 750,000 Palestinians from their villages to clear the way for Israel’s creation.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 792

US secretly sent long-range ATACMS weapons to Ukraine

Russia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 791

The protesters are also demanding an end to the 12-year-long Israeli blockade, which the United Nations says amounts to collective punishment.

The demonstrations started on March 30, 2018, and have continued since, despite the Israeli army’s deadly response.

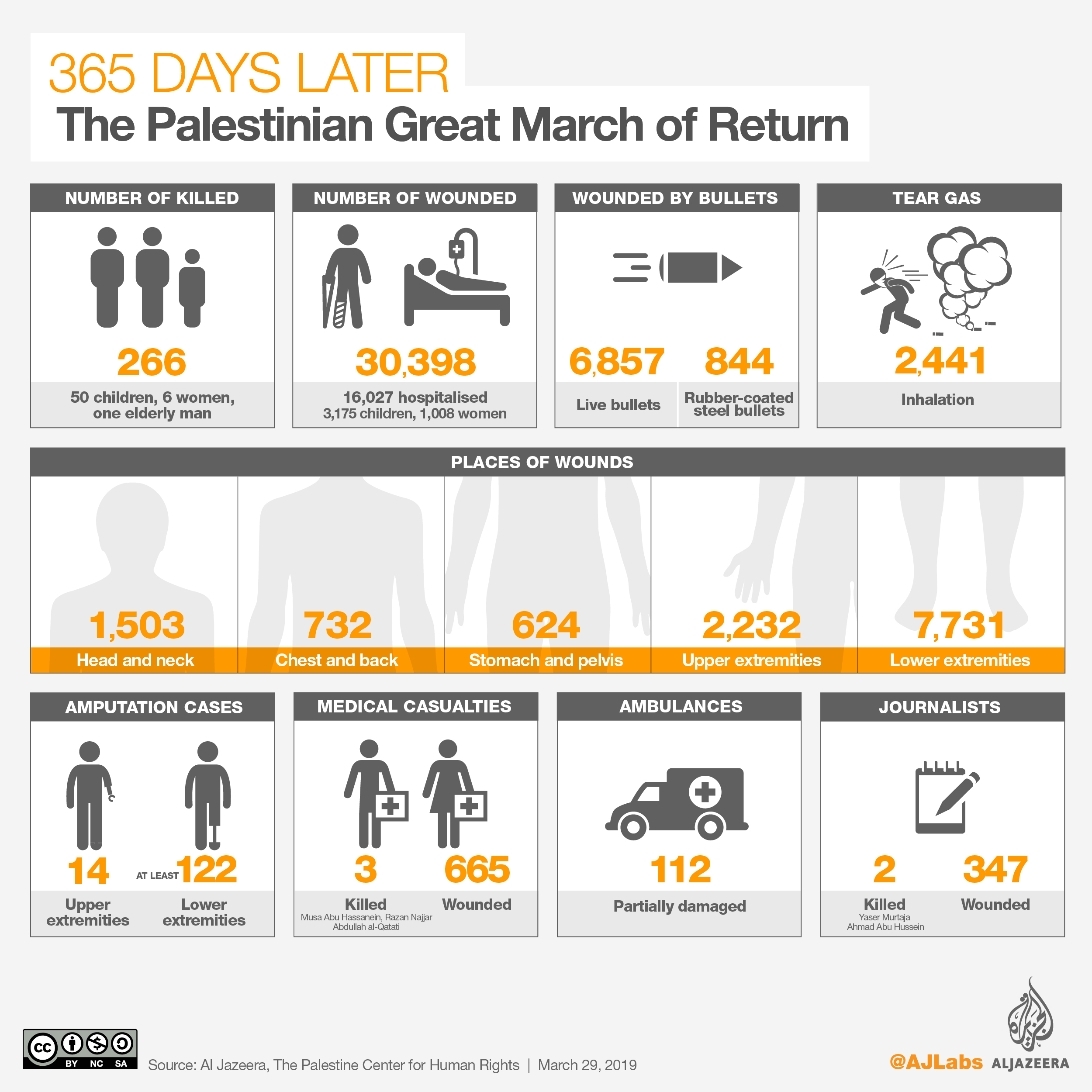

Israeli snipers opened fire at protesters during the demonstrations, killing 266 people and injuring almost 30,000 others in one year, according to Gaza’s health ministry.

Israeli blockade

The Gaza Strip is a small Palestinian territory with a total area of 365sq kilometres.

It shares its northern and eastern borders with Israel, its southern border with Egypt, and to the west lies the Mediterranean Sea.

It is home to almost two million people, making it one of the most densely populated areas in the world.

About 70 percent of its population are registered refugees.

Israel, which occupied Gaza in 1967, retains control of coastal enclave’s airspace, seafront, vehicle and pedestrian access despite ending its military presence and removing illegal settlements in 2005.

In 2007, Hamas, a self-described “Islamic national liberation and resistance movement” took control of Gaza, prompting Israel to impose an air, land and sea blockade on the Gaza Strip, isolating the enclave from the rest of the world.

Restriction on movement

Palestinians in Gaza are not allowed to move between Palestinian territories except in rare medical cases or for limited business activity.

That is mainly due to restrictions imposed by Israel on the two main crossings it shares with Gaza: Beit Hanoun in the north and Karem Abu Salem in the south.

Egypt, which also shares borders with Gaza, has closed the Rafah crossing for the majority of the last 12 years. The Rafah crossing is the only passenger crossing between Gaza and Egypt.

The restriction on movement means that many students and patients can’t leave Gaza to pursue an education or seek treatment.

Israel also controls imports to Gaza and bans almost all exports, which has led – in part – to the collapse of Gaza’s economy.

According to the World Bank, every other person in Gaza is living in poverty and the besieged strip has the world’s highest unemployment rate at over 50 percent, with youth unemployment at over 70 percent.

The UN says Gaza has become profoundly dependent on aid.

Only five percent of Gaza’s water is safe to drink and 68 percent of its population suffers from food insecurity, according to UN figures.

People also get as little as four hours of electricity a day.

Israeli military offensives

The effects of the blockade on daily life in Gaza have been amplified by Israeli military offensives on the besieged strip.

Three major operations in 2008/09, 2012, and 2014 have killed more than 3,500 Palestinians, including hundreds of children, and injured more than 15,000 people, mostly civilians.

The effect on infrastructure has been devastating with schools, mosques, UN facilities, and hospitals being hit.

More than 90 Israelis were killed and hundreds injured in the three operations. Most of them were members of the Israeli army.

Israel said the operations were meant to stop Palestinian rockets being fired from Gaza towards Israel.

Political divisions

Political divisions between Fatah and Hamas have only fuelled the public’s frustrations further. The two parties have failed time and time again to reconcile their decade-long differences, despite several agreements that were signed over the years.

In April 2017, the Palestinian Authority based in Ramallah took a series of punitive measures, including cutting salaries of employees in Gaza, in a bid to pressure Hamas to hand over its control of the enclave.

Diana Buttu, a Palestinian human rights lawyer, said that while the Fatah-Hamas split is adding to the problem in Gaza, it is not the source of it.

“The source of the problem is the [Israeli] occupation, that Israel is shooting and killing with impunity, that Israel is maintaining a blockade with impunity,” Buttu told Al Jazeera.

March of return

In January 2018, a Facebook post by Palestinian journalist and poet Ahmed Abu Artema prompted a widespread protest movement.

Abu Artema called on Palestinian refugees to gather peacefully near the fence with Israel and attempt to return to their pre-1948 homes.

His call led to weekly Friday protests, which became known as the “Great March of Return” rallies.

Jehad Abusalim, a Palestine-Israel programme associate at the American Service Committee, said the protests were another episode in the Palestinian history of popular resistance.

“The Great March of Return has been a grassroots social movement that included the various and diverse components of the Palestinian civil society,” Abusalim told Al Jazeera.

“Political factions, NGOs, people from all across the political spectrum participated in the March,” he added.

Buttu thinks that while the protests have not achieved their stated goals, their influence on shifting public opinion has been important.

“While Israel is not being held to account yet before the International Criminal Court or in the international arena, one thing that has happened is that we are seeing a sea change,” Buttu said.

“This is beginning to shed a little bit of light and open a door for people to open their eyes and see what Israel is really about,” she added.

|

|