India elections: Will farm crisis be PM Narendra Modi’s undoing?

As the world’s largest democracy votes, Al Jazeera visits a village to understand the festering crisis in rural India.

Mandya/Koppal, Karnataka – It is a discomfiting question to pose to residents of Volagerehalli, a village in Mandya district in the southern Indian state of Karnataka: “Why are farmers in your village committing suicide?” They’re unaware that Volagerehalli reported five suicides in two years between 2015 and 2017, but not shocked to hear this.

But one suicide, that of Srinivasu on April 1, is still fresh in their minds. The 45-year-old farmer, who defaulted on $7,000 in loans, left behind his ageing mother, wife and young son.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsKey takeaways from day 18 of Donald Trump’s New York hush money trial

Chad’s Mahamat Deby confirmed as winner of disputed presidential election

Why are protests against France raging in New Caledonia?

Last year, he borrowed from family, friends and moneylenders in the village to meet the costs of his daughter’s wedding. He borrowed some more this year to invest in a paddy crop on his 0.4-hectare farm. His hopes of repaying the loans evaporated when he sold his crops for a price that was well below what he had invested.

But Srinivasu’s death did not make it to the agriculture department’s statistics on farm suicides. To be counted and compensated by the state, an autopsy would have to be conducted. His family, like many others, refused to allow the procedure for cultural and sentimental reasons.

Unaccounted suicides like Srinivasu’s mean that the actual number of farm suicides in India exceeds the annual figures compiled by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB).

Although less than accurate, the NCRB data was the only reference for activists and policymakers until 2016. Since then, Prime Minister Narendra Modi‘s government has refused to release suicide statistics.

This is part of a larger pattern, where “inconvenient” data, such as the level of unemployment or economic growth have been suppressed or tweaked to suit the political narrative of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government. In 2017, for instance, the government stopped releasing crime-related statistics altogether.

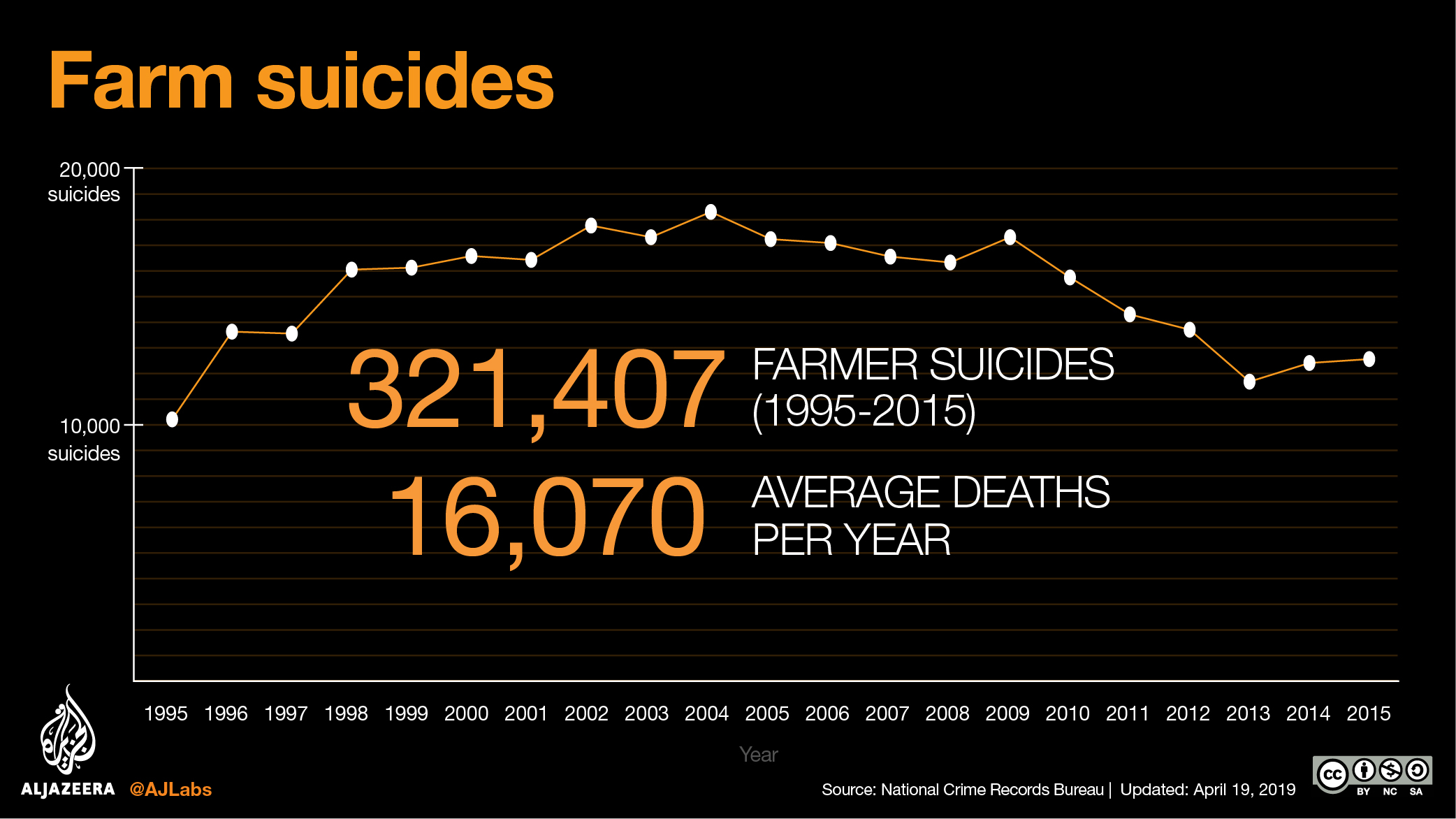

The NCRB data is an indicator of distress in the countryside, where 69 percent of India – nearly 830 million people – resides. In the two decades before 2015, at least 321,407 farmers took their lives, according to the NCRB.

The data also speaks to a crisis that goes beyond the incumbent BJP.

The Modi government was voted into power in 2014 by peasants and agricultural workers sold on the promise of a rural “revolution”, but the crisis in the countryside has only intensified.

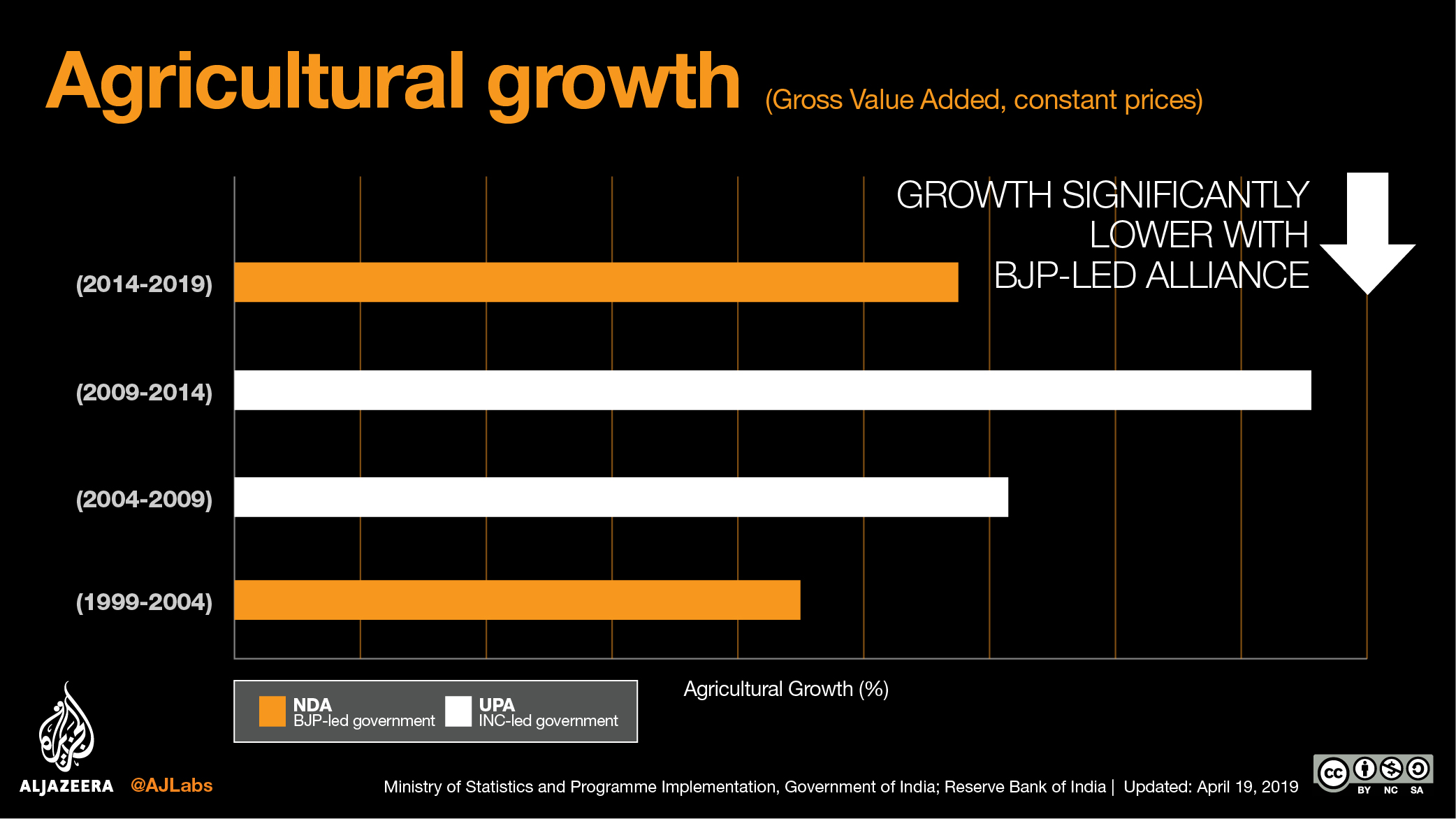

In 2014, the BJP manifesto promised farmers 50-percent profits on their production cost. As he seeks another term, Modi has asked voters to give him till 2022 to double farm incomes, a promise reiterated in the BJP’s 2019 election manifesto. Read against this promise, the macro data on the agricultural sector is hardly flattering.

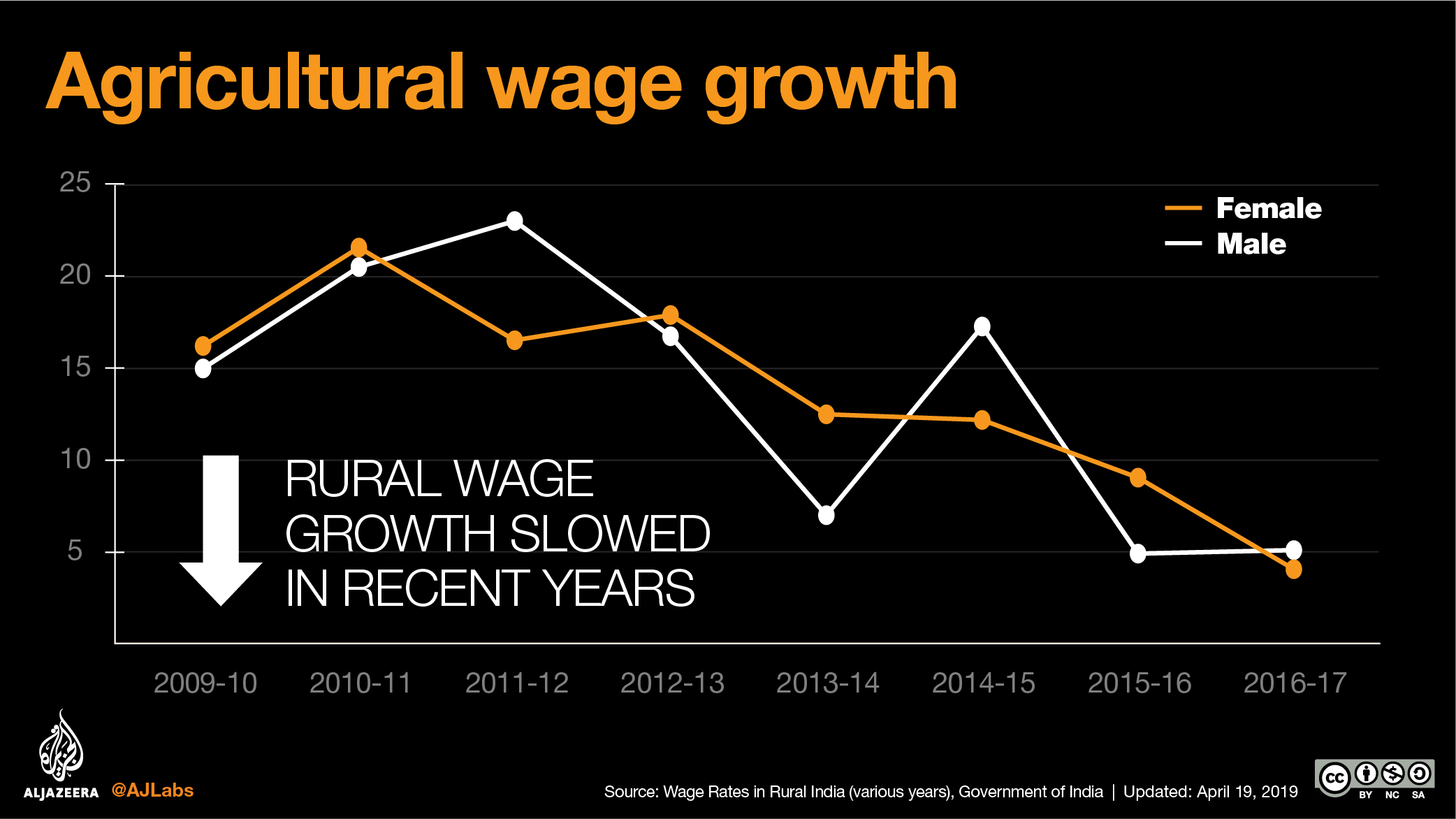

The growth in rural wages for men and women in agriculture, in real terms, also declined in recent years.

Contours of the crisis in villages

While the statistics bear out the mismatch between the BJP’s promises and its performance, to not see the rural crisis as a structural one would be to miss the woods for the trees.

The situation in Volagerehalli – a village where most of the land is channel-irrigated and farmers grow paddy, sugarcane and mulberry – serves to illustrate this.

Interactions with families of the five farmers who committed suicide between 2015 and 2017 unveil human tragedies that expose the fault lines in the political economy of rural India.

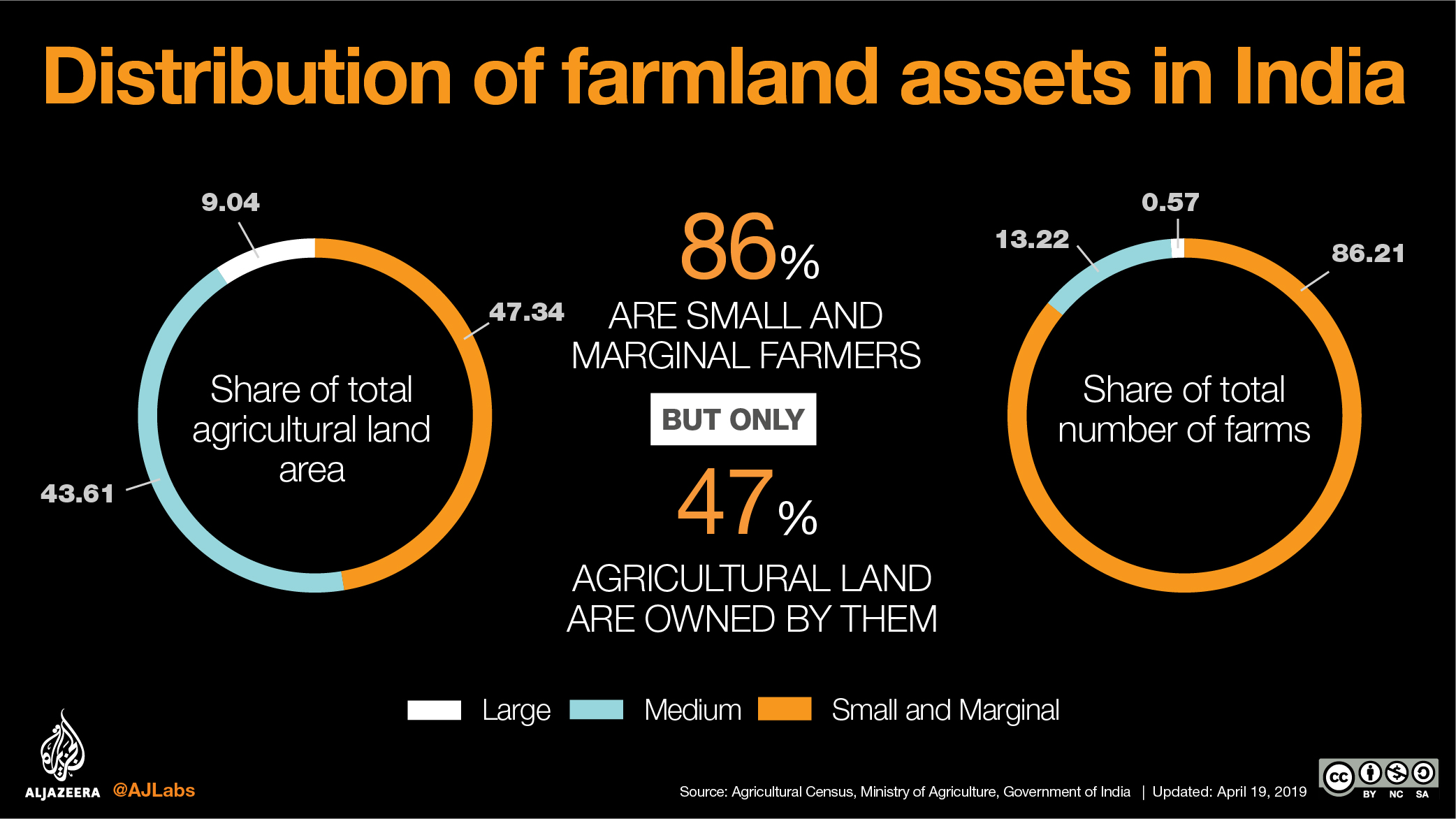

All five farmers – Jayaramu M, 36, Madhukar, 40, Naathappa, 46, CM Sampathu, 37, and Marigowda, 50 – owned less than two acres (0.8 hectares) each, below the national average of 2.7 acres (1.1 hectares). Their families also worked as agricultural labour on other farms.

All five farmers failed to make a profit and were neck-deep in debt. They borrowed to meet expenses varying from healthcare and weddings to farming investments.

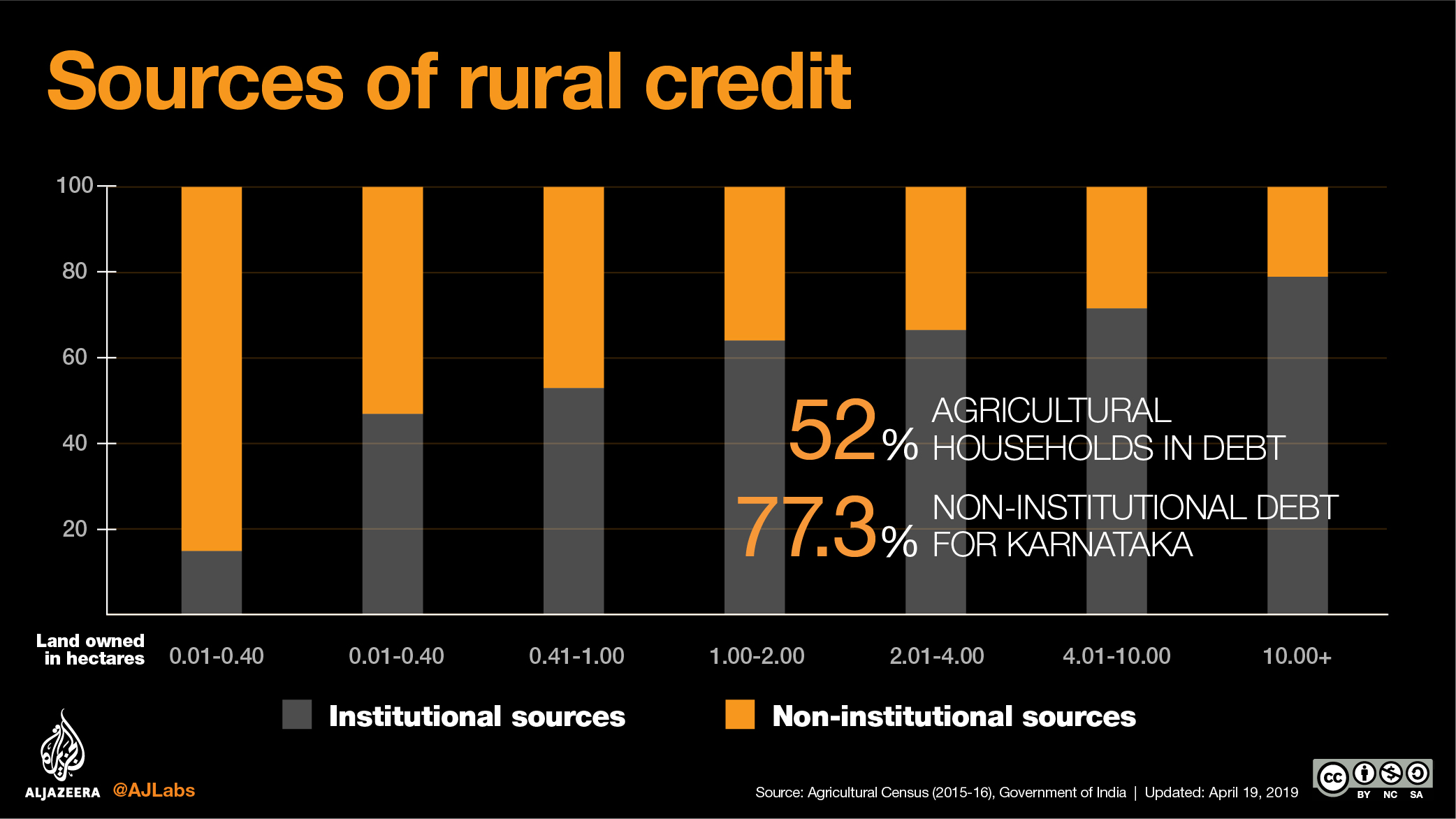

The bulk of their borrowings were from neighbourhood moneylenders, not banks; interest rates were as high as five percent a month. Sanamma, 58, whose son Jayaramu killed himself in July 2015, said that the state government’s compensation could only cover the interest portions on her son’s outstanding loans.

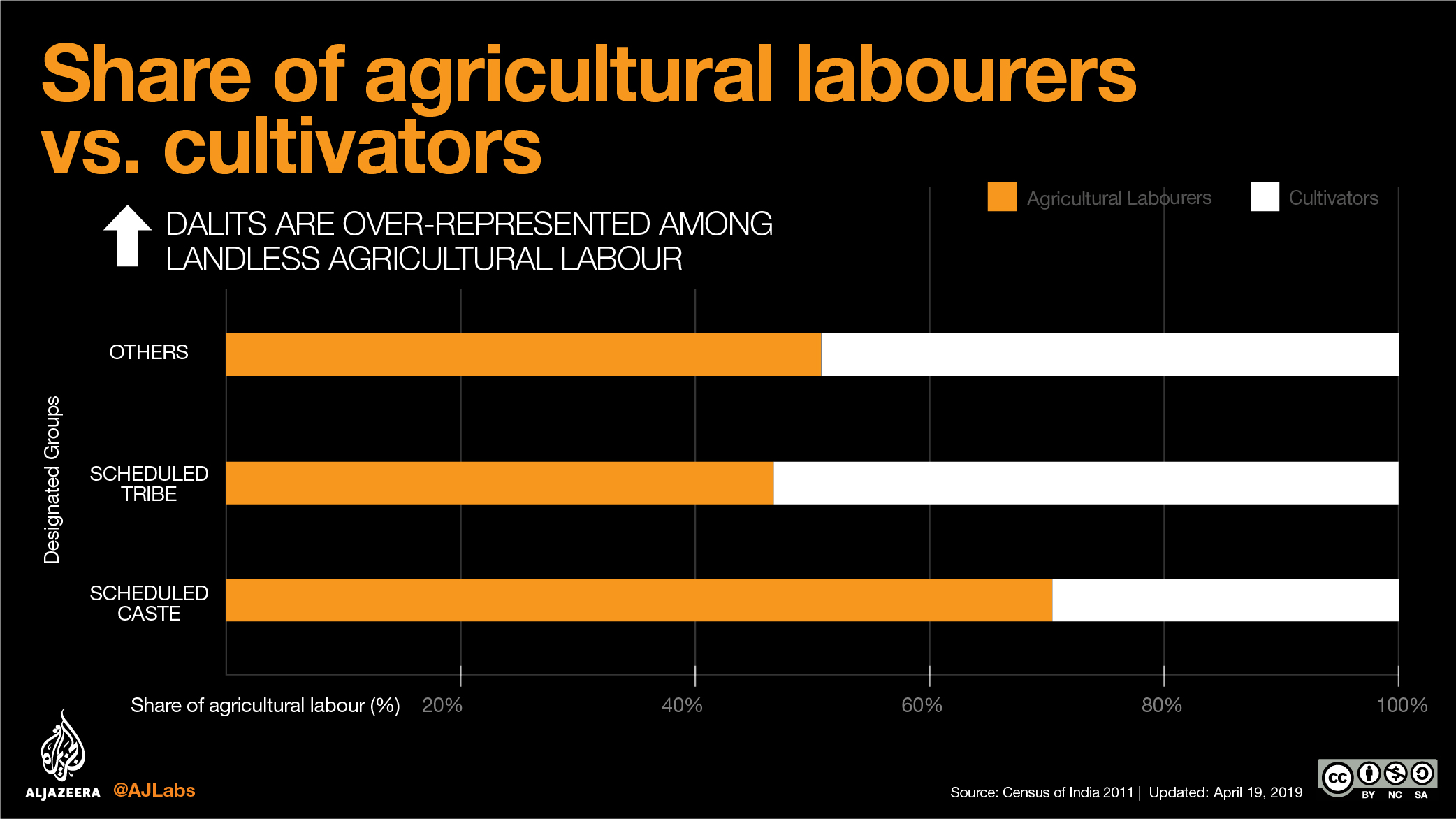

Madhukar, a Dalit, was charged a higher interest rate of nearly nine percent; he had borrowed to pay rent for the one-acre (0.4-hectare) tenancy he had recently taken up. This is common because moneylenders consider Dalits and other landless poor to be high-risk borrowers without the assets to secure their usually small loans.

After Madhukar committed suicide, his widow, Sunanda, 30, says she was forced to sell their half-acre (0.2-hectare) farm to repay his debts. The family now owns no land and she works in a garment factory to make ends meet.

The government categorises the men who killed themselves in Volagerehalli as “small and marginal farmers” in the agricultural census. They are 86 percent of the Indian farming population, says the census, but own only 47 percent of agricultural land.

It is this 86 percent that bears the brunt of the Indian farm crisis. As farming suffers, Indian farms become more fragmented with each passing generation. The inequity in the distribution of land has also intensified.

Large parts of India, including Mandya, witnessed a drought for two consecutive years since 2014. Yet, none of the families received any drought relief from the central government.

The village accountant for Maddur Taluk attributed their exclusion to procedural issues such as improper land documentation or farmers not updating their bank accounts with their biometric identification numbers, or Aadhaar.

They were not even covered by the Modi government’s flagship crop insurance scheme, the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana, which requires both the state and central government to pay part of the premium along with the farmer.

Farmers in Volagerehalli said the scheme was not useful because it allows insurance claims only if the entire village faces crop failure. Moreover, the scheme does not cover cash crops, leaving out all those who cultivate sugarcane here.

![Sanamma's 30-year-old son Jayaramu killed himself on his field in 2015 after two successive crops failed [Deepa Kurup/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/5705f595340a4606af8209fbc947d632_19.jpeg)

The scheme, which accounted for over a quarter of Modi’s 2018-2019 Agricultural Budgetary allocations worth 576 billion rupees ($8.2bn), is illustrative of how government spending increasingly ends up benefitting corporates.

Of 18 insurers under the scheme, 13 are private companies, all subsidiaries of some of the biggest business conglomerates in India, including the Reliance Group, Tata Sons, Bajaj Group and Bharti Enterprises.

A cross-section of non-BJP ruled state governments have accused the central BJP government of playing politics with drought relief.

“There’s glaring disparity – in 2018-19, Maharashtra [where the BJP is in power] got an allocation of 4,700 crore rupees ($676m) for drought relief. But Karnataka, which is experiencing a most severe and extensive drought, only got 949 crore rupees ($136.5m). It is inhuman to play politics with drought relief,” Karnataka’s rural development minister and Congress party candidate for the Bangalore North parliamentary constituency, Krishna Byre Gowda, told Al Jazeera.

The BJP’s DV Sadananda Gowda, union minister for statistics and planning and former chief minister of Karnataka, refuted the charges.

“This is bundle of lies. The devolution of funds from the central government to Karnataka in the past five years was 2.4 lakh crores ($34.5bn), three times more than what the Congress gave.”

The problem of prices

Politicians often blame the rain for the farm crisis, but for farmers in the Mandya, Koppal and Kolar districts of Karnataka, the crux of the agricultural crisis is prices.

The prices farmers receive for their crops are seldom remunerative and, adding to the uncertainty in the farmers’ lives, they fluctuate.

Chikkathayamma, 42, whose husband Marigowda, 50, ended his life on his paddy field, says: “We’ve seen many droughts over the years, we know nature does as it pleases. But what my husband couldn’t bear is that he had to sell his paddy at a cost that wouldn’t even recover the cost of fertiliser and manure that year.”

After his death, she and her son switched to a cash crop, sugarcane, on their two-acre (0.8 hectare) farm. They sold their recent crop for 2,400 rupees ($69) per metric tonne.

It was 350 rupees ($5) below the government-set Fair and Remunerative Price (FRP), the minimum price that sugar factories are legally mandated to pay farmers. And even that payment was delayed by the factory by four months.

“By the time the payments arrived, interests had piled up on the loans we had taken for the crop. The FRP itself is lower than our input costs. And, we have sold for a price lower than the FRP,” explained Chikkathayamma.

![A farmer works in his fields in Koppal district's Gangavathi village in southern Indian state of Karnataka [Deepa Kurup/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/f0dc83c224c2479dace404269ac92152_18.jpeg)

The central government claims that the FRP it fixes is 77 percent higher than the cost farmers incur to raise their crop, a claim refuted by every sugarcane farmer interviewed. The government formally withdrew from the market when the sole public sector sugar factory in the district closed up shop in 2013.

During the cane crushing season in 2017 and 2018, farmers took to the streets in large numbers in Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra and Punjab.

The government has been more responsive to demands by sugar industry lobbies – many of them owned or controlled by politicians.

As sugar prices in the global market fell, India, the second largest sugar producer in the world, scrapped export duties on sugar. Earlier this year, the government also approved soft loans of up to 105 billion rupees ($1.5bn) for sugar mills.

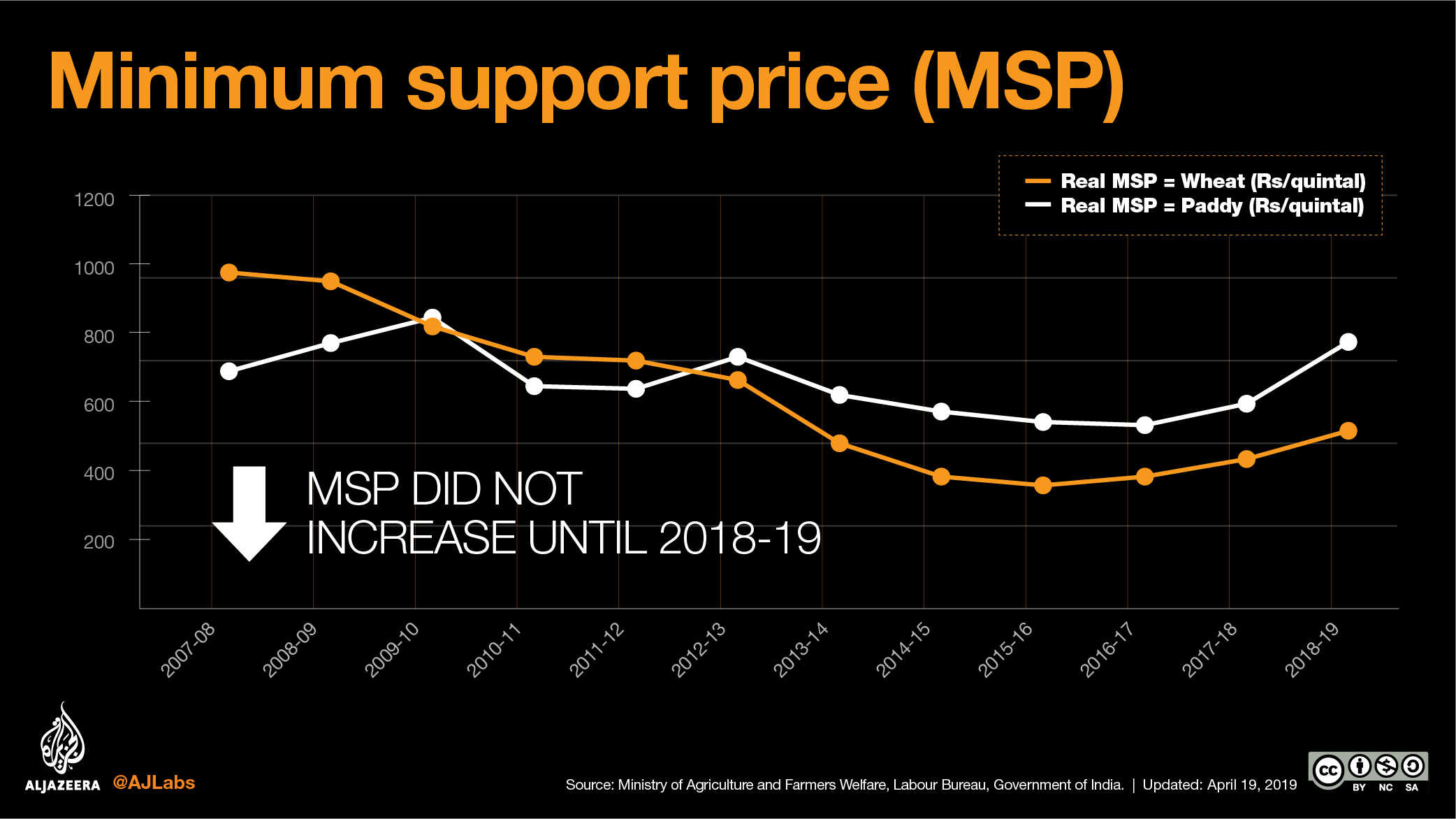

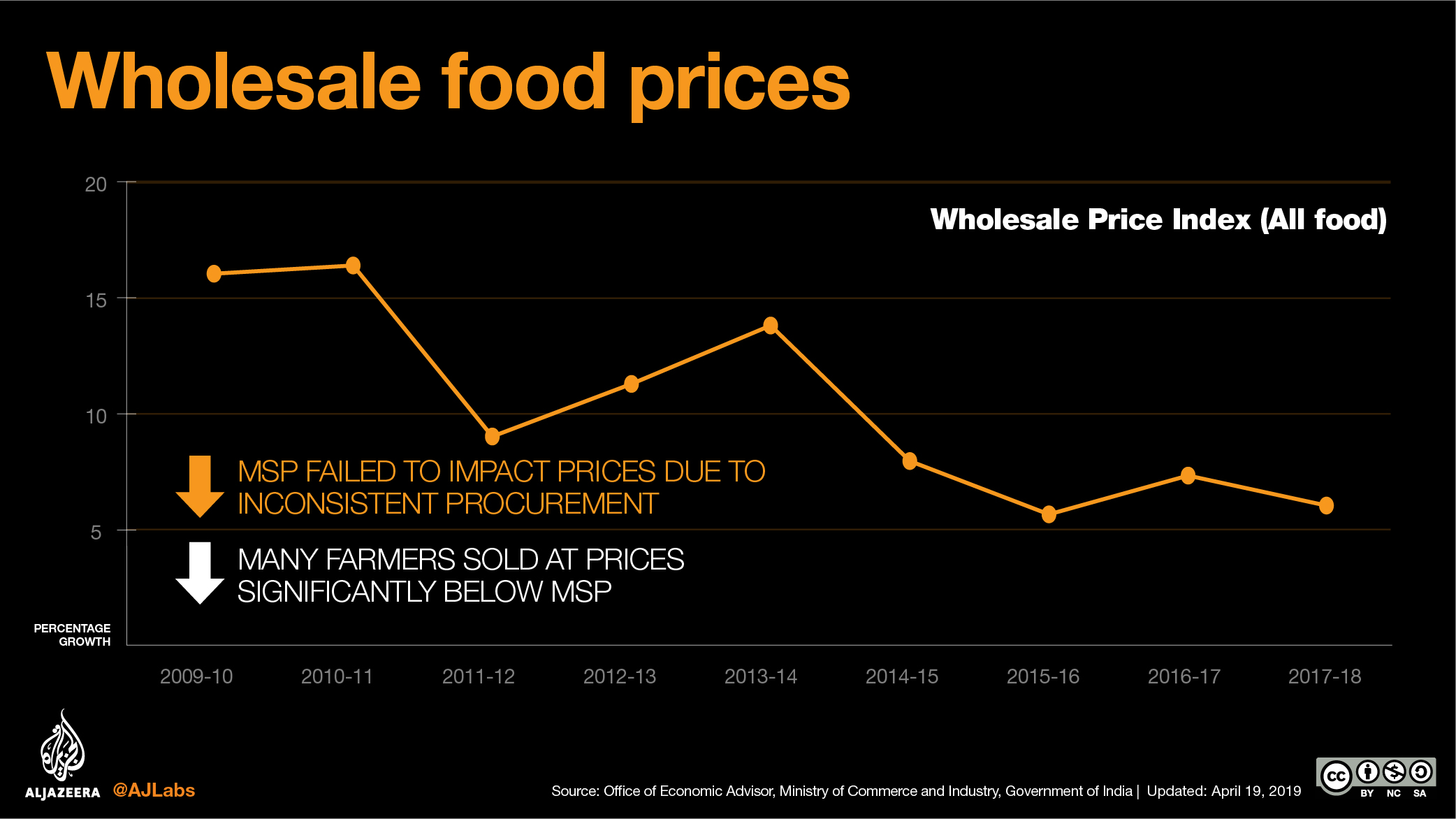

The BJP has been accused of reneging on its promise to farmers. The Minimum Support Price (MSP) – the price at which the government buys from the farmer – was stagnant for the first four years. The MSP is the government’s main instrument to ensure price stability by setting a floor price in the market.

This was official policy as the government told the Supreme Court in an affidavit in 2015, that “mechanical linkage between MSP and cost of cultivation may be counterproductive” and would “distort the market”.

It was not until 2018 that Modi announced what he termed an “historic” increase in MSPs, which he claimed fulfilled his poll promise to ensure 50 percent profits over farmers’ production costs.

But the increase was not just four years too late but also insubstantial as it calculated production costs without considering land rents. This left out large numbers of tenant farmers who cultivate hired land.

According to reports from many Indian states, the MSP failed to impact prices as government procurement was delayed and inadequate.

Paddy growers in the Mandya and Koppal districts of Karnataka say government procurement processes started only 45 days after harvest. Small farmers said they cannot afford to sell to the government as it delays payments, sometimes for months together.

So, they had no option but to sell their produce to private traders at a price at least one-third below MSP.

Liberalised trade policies have added to the crisis. In commodities such as wheat, pulses and milk products, indiscriminate imports have contributed to the uncertainty in prices.

In Volagerehalli, it is the sericulturists who are directly exposed to the caprices of the international market.

Sarasamma’s world turned upside when the government reduced the import duty on raw silk in 2015. In January 2016, her husband Nathappa sold his cocoons for 80 rupees ($1.15) per kg, a quarter of what he would usually make. “He took his own life within the week,” the 37-year-old widow recalls.

Demonetisation a body blow

The drought-hit countryside was limping back to normalcy in November 2016 when Modi delivered a monetary shock to the Indian economy.

Overnight, about 85 percent of the national currency was demonetised in a “note ban” that he said would crack down on unaccounted or “black” money and starve “terrorists” of cash.

Two years later, India’s agriculture ministry admitted to a parliamentary panel that demonetisation disrupted agricultural markets. Indeed, demonetisation couldn’t have been timed worse: farmers were either selling their monsoon crop (kharif) or purchasing seeds and inputs to sow their winter crops (rabi). Cash shortages stalled both activities.

The note ban effectively disrupted agricultural supply chains. The government backtracked from its assessment within a week with a fresh report hailing demonetisation for “formalising the agricultural sector”.

Government verdicts notwithstanding, every farmer interviewed had a tale of hardship to tell about the time cash was sucked out of the economy.

Prices fell steeply and farmers sold in panic at two-thirds the market price. But it was the hardest on small and marginal farmers, who borrow to raise money to purchase seeds and fertiliser. Moneylenders withdrew from the market fearing a crackdown by authorities.

Agricultural labour was also hit hard. It was harder to find work as farmers couldn’t pay workers.

When work dries up in the village, agricultural workers typically move to towns and cities to work in India’s booming construction industry, which employs around 50 million workers.

But demonetisation and the roll-out of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017 slowed down construction sector activities. This meant that this vital escape hatch was shut. In Koppal in north Karnataka, hundreds returned home to their villages.

“Work is hard to come by in the village as farmers are switching to machines, and fewer crops are cultivated,” Malaksaab, 37, a landless worker from Koppal’s Kushtagi, said.

“This was like rubbing salt in our wound … we couldn’t return [to construction work] for six months!”

The government also failed to scale up or ensure implementation of its flagship employment guarantee scheme, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS). The government delayed payments routinely. What could have been an important lifeline for the rural poor in the wake of such a wide collapse of livelihoods languished.

Farmers fought back

In recent years, the crisis in rural India has often spilled over onto its urban streets. Sporadic protests where farmers burn or destroy their produce to protest crashing prices have made for alarming visuals.

Incidences of riots due to agrarian distress increased fourfold from 628 in the previous year to 2,683 in 2015. This nearly doubled in 2016, the last year for which national crimes data is available.

But the protests also got more organised. Till 2017, farmers’ organisations held large marches and protests in federal state capitals. Demonetisation, and the ensuing intensification of the crisis in prices, shifted focus to the central government.

That year, around 150 farmers organisations formed the All India Kisan Sangharsh Coordination Committee, demanding remunerative prices and a waiver on outstanding loans. The wave of protests reached India’s capital New Delhi with four massive rallies in 2018.

These agrarian protests are also distinctive because they represent a wide social coalition.

“It is significant that our mobilisations drew participation that cut across diverse strata of rural society,” Vijoo Krishnan, joint secretary of the All India Kisan Sabha, a peasant organisation with over 16 million members, said.

“Landless agricultural workers, peasants, tenant farmers, Adivasis [scheduled tribes] and Dalits [scheduled castes] joined the protest in large numbers.”

The rural vote

The BJP’s electoral losses in three key states in 2018 were widely attributed to the rural vote. Since then, state governments cutting across party lines have announced loan waivers and cash transfer schemes for farmers.

In February this year, the BJP rolled out a national cash transfer scheme of Rs 6,000 ($86) a year for small and marginal farmers. The Congress manifesto promised a minimum income guarantee of the same amount every month to 50 million poor Indians.

National and regional political parties have released manifestos laden with promises to the farmer. The BJP also promised interest-free loans up to one lakh rupees ($1,445) and pensions for small and marginal farmers. Congress promised a nationwide waiver on outstanding farm loans and a separate budget for farmers.

Whether the rural voter will weigh these promises against a longer-term assessment of how political parties have handled the decade-long festering crisis remains to be seen.

For now, not all farmers in Volagerehalli are buying it.

“What about prices? How does money [cash transfers] ensure that the next time I sell my produce, I am not going to come back and kill myself? How do I know the next time you’re here, you’re not going to be talking to my family?” asks 32-year-old farmer, Umesh, visibly wounded from having lost yet another village-mate to what he calls an “endless man-made tragedy”.