Cambodia’s lifeline threatened as Mekong recedes to historic low

Dams, low rainfall and changing climate blamed for decline in river’s fortunes amid worries about crucial food supply.

Phnom Penh, Cambodia – As world leaders meet in New York from Monday to discuss the global challenge of climate change, thousands of kilometres away people in Cambodia are grappling with dramatic changes to the country’s ecosystem, including the lowest water levels in the crucially-important Mekong River ever recorded.

The United Nations Development Programme, which partners with the Cambodian government on climate, says the country is among the three most vulnerable areas in Asia.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsKenya flooding death toll climbs to 70 since March

At least 155 killed in Tanzania as heavy rains pound East Africa

Scientists say Oman, UAE deluge ‘most likely’ linked to climate change

“[Cambodia] is highly vulnerable due to a relatively low adaptive capacity,” said Nick Beresford, UNDP Cambodia’s Resident Representative.

“Agriculture is mostly rain-fed, and most infrastructures are not yet climate-resilient,” he added, warning that many households would probably be unable to withstand “climate-related shocks” like droughts or floods.

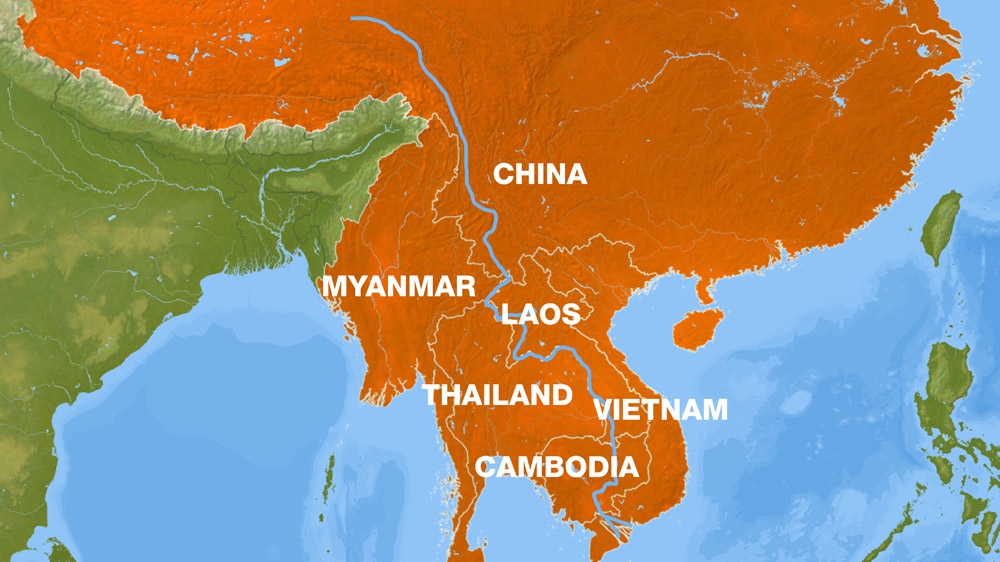

In July, the Mekong River Commission reported water levels below any on record for the Mekong River, which stretches for some 4,500 kilometres (2796 miles) from its source in China through Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia before emptying into the South China Sea in Vietnam.

The commission, an inter-governmental agency set up to help manage a river of crucial importance to millions, cited “very deficient rainfall” and numerous upstream dams for the lack of water in a situation it described as “unprecedented”.

Cambodia’s Tonle Sap lake is the largest freshwater lake in the region and provides Cambodia with 500,000 tonnes of fish, about 70 percent of the country’s total protein intake.

The lake is fed by a tributary of the Mekong which reverses course when the larger river floods. This year, the Tonle Sap reversal happened much later than usual.

Brian Eyler, author of Last Days of the Mighty Mekong and head of the Stimson Center’s Mekong Policy Project, has been following the water levels closely.

With more than 100 dams now operational on either the mainstream Mekong or its tributaries, Eyler warns that the dams are preventing fish migration and sediment flow that is vital for agriculture.

Eyler said the dams also reduce the intensity and duration of the Tonle Sap reversal.

“Climate change is now delivering shorter monsoon seasons – this too reduces the intensity and duration of the Tonle Sap River’s reversal,” he said, adding that rain falls less often, but falls more intensely, leading to droughts in some areas and flooding in others.

“Many fish died because of the shallow water, hot temperature, and toxic water resulting from lack of oxygen. Around 2.5 million people who depend on the lake’s once-abundant fisheries have been directly affected” – Tonle Sap Lake Waterkeeper Senglong Youk https://t.co/HVLi7PwRYE

— Waterkeeper Alliance (@Waterkeeper) August 31, 2019

Eyler warned that should the Tonle Sap not reverse, the ecosystem would be “irrevocably damaged” and the Cambodian diet “severely affected”.

Eyler praised the Cambodian government for exploring a shift towards solar power and an apparent reluctance to build new dams on the Mekong. However, he said the government should immediately be preparing alternative protein access through aquaculture and agriculture.

“Cambodia is likely ill-equipped to shoulder a major shock to its food supply, so a crisis delivered by a failure of the Tonle Sap River to reverse could be looming on the horizon. This could trigger major out-migration from Cambodia to neighbouring countries and challenge the capacity of the Cambodian government to maintain stability within the Kingdom,” he warned.

But the Tonle Sap is not the only danger Cambodia faces as the climate changes.

“Rising temperatures are expected to have an impact on worker’s health and productivity, particularly in agriculture, industry and construction sectors which are very exposed,” Beresford said, adding that agriculture will also be affected.

Beresford said Cambodia adopted a 10-year climate change plan in 2013, dedicating nearly $200m to the issue.

“Public funds have been primarily allocated in support of adaptation activities, with a focus on irrigation, climate-resilient roads, agriculture, access to clean water and sanitation,” Beresford said.

But Cambodian environmental activist Sun Mala, who was arrested in 2015 for protesting against sand-dredging, doubts the government’s commitment to the environment.

Politicians and politically-connected businessmen have frequently been linked to environmentally-damaging activities like sand-dredging and illegal logging.

“We can’t expect Cambodia to take action to stop deforestation or anything harmful to nature,” Mala said, explaining that powerful people benefit too much from the exploitation of resources.

Mala said Cambodia is also in an unfortunate position as a downstream country on the Mekong River.

“On the mainstream, China and Thailand build a lot of dams, so in the dry season they keep the water in the reservoir and in Cambodia we don’t have enough water to generate electricity,” Mala explained, referring to countrywide blackouts earlier this year.

Mala also said the government has not come up with an effective plan to replace lost jobs or protein sources.

“So far they just say when you cannot catch fish any more or grow agriculture on the river, just change and have a chicken or pig farm,” he said.

Buying a farm is simply not an option for many of the poorest people.

All along the Tonle Sap, communities live in floating homes, depending almost entirely on their catch for survival.

Many are ethnic Vietnamese who had their documents revoked during a government purge in 2017, leaving them stateless and unable to legally acquire land in Cambodia.

“When the water is high, when the water is low, they always fish,” said Mao, a resident of Kampong Chhnang where two such floating villages are located.

While many of the villagers have jobs common in any community – including mechanics and shop owners – Mao said the village as a whole is primarily dependent on fishing.

He said water levels were unusually low earlier this year, and the rain came much later than normal.

Although the water has risen substantially as of late, Mao said it was still lower than the same time last year.

“It used to go up to the top,” he said pointing to the riverbank which still had approximately five metres exposed.

Mala worries about future droughts on the Tonle Sap and the risk of starvation.

“In the future, it could be very dangerous,” he said.

Despite the bleakness of the situation, Mala tries to stay positive, taking solace in how many young people are becoming environmentally active.

“It’s hard to imagine but I hope that because of the peoples’ environmental movement we can stop the destruction of natural resources,” he said.