What’s in a photo? A lot for Lebanon as talks with Israel begin

Whether to take a commemorative photo is just one of the tricky protocol issues surrounding the maritime borders talks.

Beirut, Lebanon – Lebanon’s landmark border talks with Israel have raised a thorny issue: how to negotiate with a state you do not officially recognise and consider to be an enemy.

It’s a question that filters down to the very mundane, including the manner in which both delegations greet each other – and even whether they take a commemorative photograph.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAnalysis: The politics behind the Lebanon-Israel border talksAnalysis: The politics behind the ...

Lebanon’s COVID-19 surge: What went wrong?Lebanon’s COVID-19 surge: What went ...

To rebuild Lebanon and its economy, uproot corruptionTo rebuild Lebanon and its economy, ...

Lebanon and Israel are technically at war, with the latter fighting a bloody 2006 conflict with Hezbollah, the Iran-backed group.

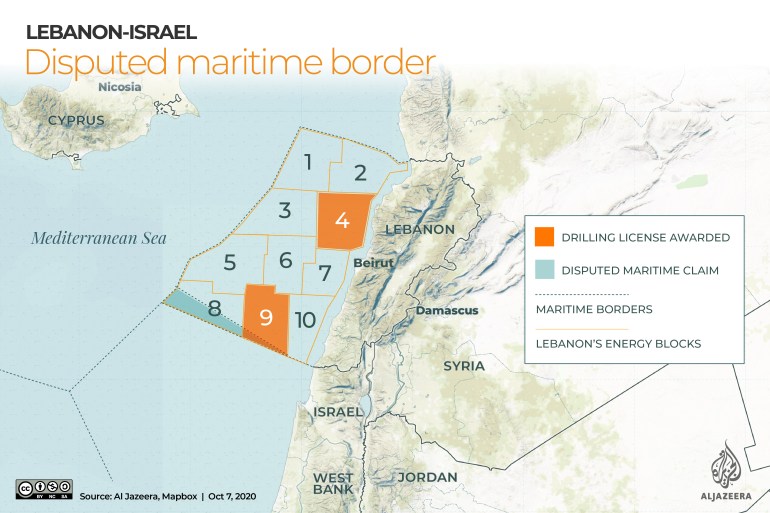

Open-ended, United States-mediated talks to demarcate the countries’ maritime border – a decade in the making – finally began on Wednesday at a United Nations base on Lebanon’s southern border.

Hezbollah and its main ally, the Amal Movement, said in a joint statement on Wednesday that Israel was trying to push Lebanon towards some form of normalisation with Israel, less than a month after landmark US-sponsored normalisation agreements between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.

Pro-Hezbollah newspaper Al-Akhbar said the two groups also rejected a “normalisation-style picture” in the form of a commemorative photograph.

Lebanese army spokespeople could not be reached for comment on whether a photo had indeed been taken. None has yet been published.

Such a photo would have large propaganda value for both Israel and the US, but would embarrass Lebanese parties that draw legitimacy from so-called “resistance” against Israel.

Laury Haytayan, Middle East and North Africa director of the Natural Resource Governance Institute, told Al Jazeera: “They can take the picture and send it to [US President Donald] Trump, and he says ‘I’m Mr. Peace and Stability, I can even make the Israelis and Lebanese sit round the table to negotiate normalised relations.’”

A Lebanese presidential source told Al Jazeera that President Michel Aoun had discussed Lebanon’s etiquette at the talks with the delegation and rejected any form of normalisation – but said they had decided to leave the issue of the photograph up to the UN.

At the negotiations, the two sides have gotten closer – if only physically.

Under a 1996 understanding that ended Israel’s two-week Operation Grapes of Wrath military campaign against Lebanon, the Lebanese and Israeli militaries coordinated on security issues from “two separate rooms, with someone mediating in between”, Elias Hanna, a retired Lebanese Army general, told Al Jazeera.

“Now it’s direct, in the sense that they’re in the same room, sitting close to each other,” he said.

Still, he said protocol would likely remain the same: “No picture or greeting, no gestures or wink – don’t even look, it’s forbidden” he said.

Brigadier General Bassam Yassine, the head of the Lebanese delegation, made no reference to Israel itself during Wednesday’s talks, instead referring to “other parties,” according to a transcript published by the Lebanese army.

The talks broke up after an hour, with Lebanese state media reporting a second round to be held on October 28.

But some in Lebanon are now saying that the country’s attitude should be subject to change, especially as it seeks to explore for oil and gas in the hydrocarbon-rich waters of the eastern Mediterranean.

As the talks were ongoing, Ziad Assouad, a member of President Michel Aoun’s party, said Lebanon’s dire economic situation meant that it should have no qualms about holding even direct negotiations with Israel – a notion that remains taboo.

“What’s the difference if I speak through another side or directly?” Assouad asked on a morning TV show.

“We can’t solve it via war and don’t have the economic power to do that, and I’m waiting for the oil to pay off [part of] our debt … So why do Lebanese want to live in this duality?”