What next for Tanzania’s opposition after election wipeout?

Observers say a comeback for opposition parties seems a long way off, relies on reformation of existing political system.

It has been more than a month since a widely disputed presidential election in Tanzania that incumbent John Magufuli won in a landslide, and the country’s opposition parties are still reeling from the wipeout.

Along with Magufuli’s re-election, the massive victory secured by the governing Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) in the legislative polls also held on October 28 has all but eradicated opposition representation in Parliament, creating a de facto one-party government.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsTanzania’s Magufuli sworn in for second term after disputed vote

What is behind Tanzania’s authoritarian turn?

This has crippled the opposition parties’ ability to influence lawmaking and leaves them without a major platform to voice their views, as Magufuli has banned political activities outside campaign season.

With little clarity about the next steps forward, many observers agree the opposition’s future does not look promising.

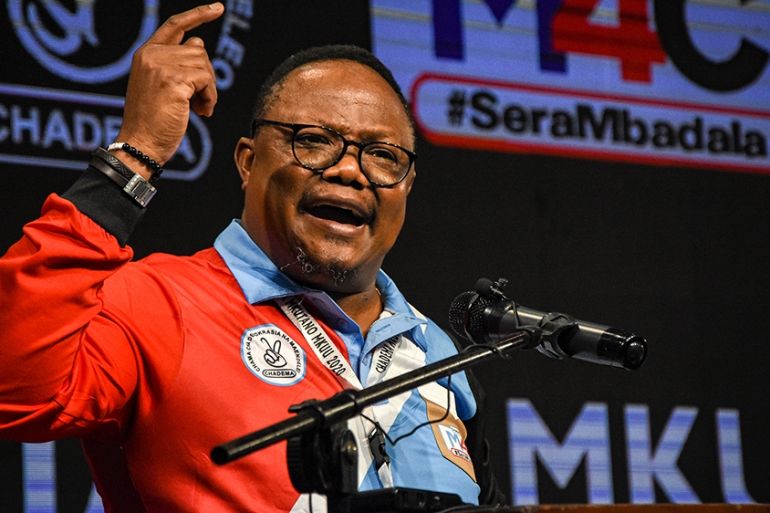

Both main opposition parties, Chadema and the Alliance for Change and Transparency-Wazalendo (ACT-Wazalendo), have alleged irregularities and rejected the results, but with few obvious options available, some party members have turned to litigation to try and make their grievances heard.

ACT- Wazalendo chairman Maalim Seif Sharif Hamad is leading a group of applicants in a case at the Arusha-based African Court on Human and People’s Rights that accuses the government of electoral misconduct.

Meanwhile, a loose alliance of activists and opposition figures is working to collect and verify evidence of election violence in both Zanzibar and on mainland Tanzania in order to file cases in the domestic courts and seek justice for the alleged victims of abuse.

Yet at the back of these cross-party efforts, rebellion has rocked the unity of Chadema after its top female politicians opted to join Parliament as special seat MPs, against the party’s standing.

In the days after the election, former Chadema presidential candidate Tundu Lissu sought diplomatic protection at the German ambassador’s residence and later left for Belgium, the country where he spent nearly three years after surviving an assassination attempt in 2017 in an unsolved case.

Lissu – who got 13 percent at the polls, compared to almost 85 percent for Magufuli, according to officials results – has pledged to continue rallying the international community to push for structural changes in Tanzania to ensure a level playing field for all political parties.

Political analyst Rashid Abdallah described the 52-year-old opposition leader’s departure as “a big blow to Chadema, especially if Lissu decides he can’t come back to the country for many years.”

“The party will have a hard time finding an influential figure like Lissu,” Abdallah said. “Perhaps they ought to start grooming one now because at the moment, they hardly have a politician that people could rally behind like they did with Lissu.”

Meanwhile in the Zanzibar archipelago, ACT-Wazalendo leaders have declared their intention to join CCM and form a Government of National Unity (GNU), despite their previous declaration that the CCM government in power is illegitimate.

GNU is a constitutional provision that invites representatives from losing parties to join the government if their share of the vote surpassed a 10 percent threshold.

The decision has attracted sharp criticism on social media from their supporters and those of other parties, with some accusing ACT-Wazalendo’s leaders of betraying the victims of election violence by putting their personal political interests first.

Opposition members have alleged that at least a dozen people were killed and many wounded in election-related violence, adding that dozens of opposition supporters were still being held in police custody and the whereabouts of others remained unknown.

The violence is likely to have left many feeling intimidated, while the alleged rigging appears to have also disappointed and demotivated many opposition supporters in a country where CCM – along with its predecessor, the Tanganyika African National Union party – has uninterruptedly been in power since independence in 1961. Indeed, only 50 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot on election day, pointing perhaps to a wider sense of disillusionment or futility with the exercise.

The election results spell financial trouble for the opposition, too. Parties are allocated funds based on the proportion of seats they hold in Parliament.

In recent years, many of the opposition’s key sources of income have dried up, and now subsidies will slow to a trickle as well.

Still, the uncertainty facing Tanzania’s opposition is unlikely to trouble the country’s leadership.

At a public rally in northwestern Tanzania in 2018, Magufuli had told the crowd that entertaining pluralism politics would only delay his development plans, saying that development does not belong to any political party.

This July, at the opening of the new building for the National Electoral Commission, Magufuli joked that if the opposition simply endorsed him as president, the money saved on the election could be spent on developing the country.

Against this background, observers say a comeback for the opposition parties seems a long way off – and some even suggest their fate depends more on the authorities than themselves.

“The return of the opposition largely depends on whether the government decides to create a fair playing field,” said Abdallah. “Otherwise, the only time that the opposition could get back onto the scene is close to the next election in 2025, just like how the authorities only allowed the opposition to conduct their political activities freely a few months before the last election.”

Abdallah went on to note that the opposition’s only seemingly realistic chance to rebound lies in the reformation of the existing political system.

“The problem is not the opposition. The problem is Tanzania’s political system, which is not friendly to the opposition. Therefore, if there isn’t any change in Tanzania’s political system, the opposition will never have a voice, as it has always been,” he said.

When the country was preparing to transition to multiparty politics three decades ago, a commission was formed to investigate and advise on the changes required to boost the chances of a successful transition.

The Nyalali Commission, as it became known, recommended repealing the constitution, curbing presidential powers and forming an independent electoral body, among other suggestions.

Some 30 years later, the president, who is a chairman of the governing party, still holds the right to form the electoral commission, while the constitution bars a losing party from challenging presidential results in any local court.

The regional election observer team Tanzania Election Watch has decried the relics of this political infrastructure, with observers pointing to the use of repressive laws and institutions in restricting the opposition’s full participation in politics.

For example, amendments made to the Political Parties Act in 2019 permit the politically appointed Registrar of Political Parties to regulate political activity and administer criminal penalties for breach of regulations.

Professor Abdallah Safari, former Chadema vice chairman, believes the opposition has no choice but to find ways to push for reform of the current political system if it is to have any meaningful participation in politics. He said the opposition’s “best option” is to fight for an independent electoral commission.

“The results of the just-ended elections have presented overwhelming evidence that it’s time now the opposition came together and fight for an independent electoral commission,” he said, calling this the opposition’s “best option”.