‘Truth telling’: The stories of Australia’s Stolen Generations

New books reveal the traumatic experiences of Indigenous children taken from their homes in official Australian policy.

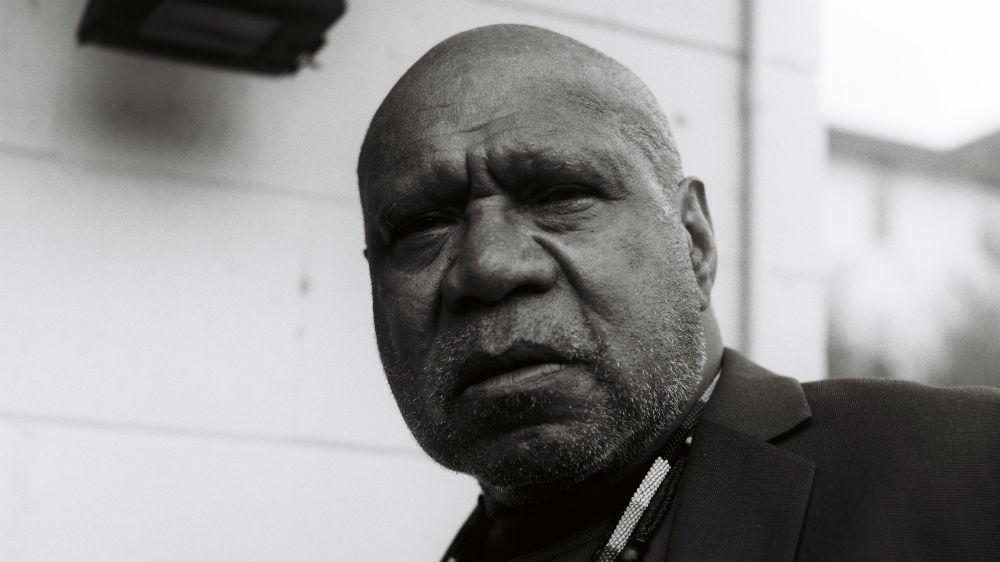

Melbourne, Australia – When Archie Roach speaks, his eyes close, deep in thought, as if taking on the countenance of an ancient, blind seer.

Reflecting on his life takes considerable courage; removed from his family as a child as part of Australia’s Stolen Generations, Roach would experience alcoholism, homelessness and even a suicide attempt before sobering up and becoming the internationally-recognised singer-songwriter most know him as today.

Keep reading

list of 3 items‘Australia thought we would die out’

Crisis of Aboriginal women in prison in Australia

His life story is now recounted in a new autobiography, Tell Me Why, which – like his music and lyrics – is written with passion, beauty and a hint of sadness.

“[Many people] hear about Stolen Generations but don’t realise the journey that one makes, or takes, to find their way back – if they do at all,” Roach said.

“I wanted to write about that, and what I’ve learned through the years.”

Now 64, Roach’s love of music came from his adoptive father, a Scottish migrant who would sing the traditional songs of his homeland around the dinner table.

|

|

After being removed as part of Australia’s policy to assimilate Indigenous children into white families, Roach was adopted into what he describes as a stable home.

It was during high school that he would receive a letter from his then unbeknownst older Indigenous sister that would set Roach on a remarkable journey to find his biological family.

After considerable time spent drinking heavily and living on the streets – including a few short stints in prison – Roach would eventually reconnect with his Aboriginal family.

Deep-seated trauma

Yet the trauma of his removal, and the impact it had had on his community, was deeply felt.

He would begin to write songs about his, and his family’s, experiences, and in 1991, rose to prominence with the song Took the Children Away.

Tell Me Why describes in considerable detail, the effect of his removal and separation would have, including on his own children and grandchildren.

“I explain to [my grandchildren] about being taken away and it’s very confusing for them at first. And they get older and they think about it and it actually upsets them when you talk about it now. Because they are hurt, because their own grandfather was taken away from their family.

“They can’t understand why that would have happened in the first place. And that’s the question they ask too – ‘why did they do that?’ [And I have to say] ‘I don’t know. They probably thought we’d be better off.'”

Along with the emotional trauma, Roach said the removals had severe cultural implications.

“You couldn’t speak [Indigenous] language – they’d lock you up. You couldn’t practise cultural practices – they’d lock you up or withhold rations.

“So we grew up and we weren’t able to teach our children and grandchildren language, dance and things like that.”

Roach said he was fortunate to eventually find his biological family, but acknowledged that there were many Indigenous children who did not.

He said he hopes that readers understand “that this happened, in this country. Not just to me but thousands of other children. And some of them never made it back. And some of us did, and were fortunate.”

An apology

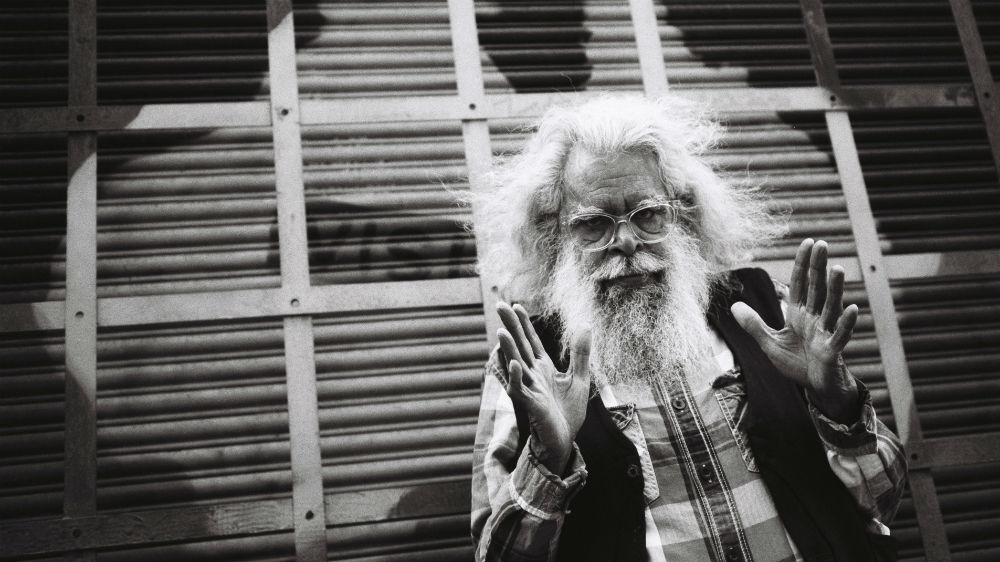

Jack Charles is another survivor of the Stolen Generations with a story to tell.

Well known as a stage and screen actor throughout Australia, his new autobiography Born Again Blakfella documents his journey through homelessness, prison and heroin addiction to emerge in his 70s as a critically acclaimed performer and spokesman for the Stolen Generations.

“I’ve always been told ‘you should write your book’,” Charles said. “It took me a while to decide to do it, and it had to come at a time when I had time to myself.”

Like Roach, Charles was also removed as a child by government authorities. Yet, while Roach was adopted into a loving family, Charles was placed into a strictly religious institution where he, along with many other Indigenous and non-Indigenous “orphans”, would be sexually and physically abused.

As a teenager, he discovered a love of the theatre, and while on one hand, he would rise to prominence as an actor, he would simultaneously remain homeless due to heroin addiction, often relying on burglaries to survive and spending time in prison.

Now 76, Charles is no longer a drug user; instead, he is a sprightly man ready to make amends, and points out that in his recent one-man play – Jack Charles vs the Crown, he even makes an emphatic apology to the victims of his burglaries.

“I apologise to all those I’ve stolen from, to all those I’ve disappointed, all those whose trust I’ve abused.”

He then added with a laugh: “Mr Rudd gave his apology, I’ve given mine!”

With this, he references former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations on February 13, 2008.

A turning point in Indigenous relations at the time, Rudd’s apology brought the issue of the tens of thousands of Indigenous children taken from their families to national prominence.

Yet Charles said Australia still has a long way to go with regard to Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations.

“We all thought [the apology] was a great idea, but Australia is uniquely and still peculiarly racist against the First Nations peoples. If they weren’t, we would not be in the dire straits that we are in still at this time in Australian history.”

Indigenous Australians are still vastly disadvantaged in every social indicator, including education, health, employment and housing, and the imprisonment rates far outweigh those of non-Indigenous Australians.

Many of these social problems stem from the intergenerational trauma of past policies such as Indigenous child removals.

Professor Steve Larkin, chair of the Healing Foundation, described the impacts of the Stolen Generations as a group of people “severely traumatised”.

‘Truth telling’

The Healing Foundation is an organisation set up to provide support and assistance to members and survivors of the Stolen Generations and their descendants, as a consequence of the institutionalisation and intergenerational trauma.

He said Kevin Rudd’s apology created an impetus “for greater understanding of the particular needs of the Stolen Generations” and also brought the issue into the public domain.

Yet he also recognises the importance of “truth-telling”; that books such as Archie Roach’s and Jack Charles will provide Australians a better understanding of a history that is often ignored.

Larkin said “truth telling” was necessary for Aboriginal communities to heal, and so that “children and future generations [will] understand the true history so they can better understand and appreciate why Indigenous people are in this situation of disadvantage now”.

“That might then lead to a far different, more positive basis from which Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians could work together.”

Archie Roach’s book Tell Me Why, and Jack Charles’ Born Again Blakfella both are significant contributions to “truth telling”.

In fact, Charles even described himself as a man “compelled to tell the truth in history” and has also spoken in Parliament about the impacts of being part of the Stolen Generations and survivor of sexual abuse.

When asked what impact he hoped his new book might have, he said simply: “Just to get to understand just one Aboriginal person’s journey – my journey.”

Equally understated, Roach had a similar sentiment, and said, “What I’d like people to get is that [the removal of Indigenous children] is something that shouldn’t have happened in the first place.

“Nobody should have to go through something like that.”