Amid lockdown, South Africa’s waste pickers suffer most

Informal waste reclaimers banned from working in streets after being excluded from coronavirus response plan.

Johannesburg, South Africa – Beauty Ncube is surrounded by large bags of paper, plastic and tin cans. Sitting on a broken office chair, she picks at her cuticles. The makeshift disinfectant she has been using has dried her skin.

“Lockdown changed a lot of things for me,” she says. “I was providing for my kids with the little money I’m getting, but now, I’m starving.”

Keep reading

list of 3 items‘Unprecedented’: South Africa goes into coronavirus lockdown

South Africans brace for 21-day lockdown as virus cases rise

Ncube is a waste picker, or reclaimer, in Johannesburg, and one of the tens of thousands of informal workers across South Africa who earn a livelihood by recovering recyclable materials from municipal waste.

For the first time in her more than 20 years as a reclaimer, Ncube has been prohibited from working in the streets due to a three-week lockdown imposed by the government on March 27 to curb the spread of the coronavirus pandemic. The measure has confined South Africans to their homes and allowed only for certain work deemed essential services to continue. While waste management was declared an essential service, the informal recycling sector was not.

Ncube admits she is “scared of this disease” but would like to have continued working, under certain conditions, to support her two teenagers.

“They told us we must not work with the rubbish, because we’re going to affect other people,” she says, with a wry smile. The irony of the rich, predominantly white suburbs where she collects waste being a breeding ground for the virus is not lost on her.

“Maybe we’re going to get infected, also.”

Workers like Ncube do not earn a salary – instead, they get paid for what they collect, usually about 70 South African rand ($3.85) a day. A typical day starts before sunrise, with waste pickers walking to suburbs far away from where they live to search through refuse bags and rubbish bins. After separating the recyclable materials, they load them onto their trolleys and haul them to waste processing and recycling plants to sell them for a small fee.

According to a 2016 report by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, these reclaimers are responsible for the recycling of 80 to 90 percent of South Africa’s used packaging and paper. It is also estimated that this informal sector saves municipalities up to almost 750 million rand ($42m) annually in potential landfill costs by diverting recyclable materials out of the waste streams.

While there is no official data, some estimates put the number of waste pickers in South Africa between 60,000 and 90,000. But with unemployment at more than 29 percent, the actual figure could be much higher.

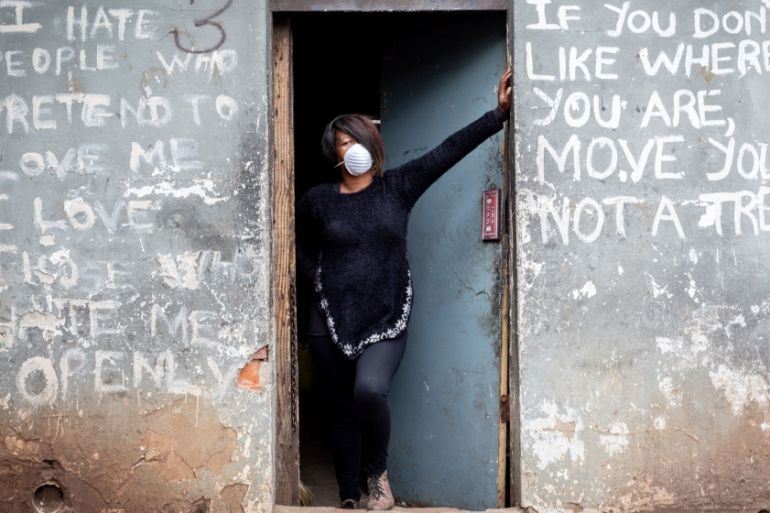

Ncube is one of some 250 waste pickers who live in an abandoned school in central Johannesburg. The community is aptly known as Bekezela, which means “to endure” or “to persevere” in isiZulu, one of South Africa’s 11 offical languages.

Over the years, Bekezela has withstood a number of violent eviction attempts, as well as pervasive prejudice and marginalisation. Ncube says she does not know why they are being treated this way – their work is important for their families, their society and their environment.

Still, the residents of Bekezela have managed to work as a collective and fight for their rights, creating bespoke recycling programmes for the community and the areas they operate in. They have also been able to secure a truck to assist with the transporting of materials, which has helped to significantly increase their daily haul.

All this has primarily happened under the banner of the African Reclaimers Organisation (ARO), an organisation founded by the community in 2018. Their long-term goal has been to eventually open their own recycling hub and plastic processing plant – but the coronavirus pandemic has brought their aspirations to a jarring halt.

“One day of no work burns the pockets, especially in a community that lives from hand-to-mouth,” says Luyanda Hlatshwayo, ARO founding member. “Twenty-one days is going to be difficult,” he sighs, shaking his head.

More than a week into the lockdown, he says the effects are already being felt by the community. Behind him, graffiti adorns the walls under the bridge. A spray-painted rhino is framed by: “I won’t give up.” Next to it is another mural proclaiming Bekezela as: “A place like home.”

Past the graffitied walls, the usually bustling streets are quiet except for the occasional police and military patrols enforcing the lockdown.

People have been donating food, but this, Hlatshwayo says, is not enough. “Who do we give the food to? How do we decide?” Two toddlers nearby clumsily chase a chicken. His people are starving. “This is the true coronavirus crisis – here, at the bottom of the food chain.”

According to the World Bank, more than a quarter of a century after the end of apartheid in 1994, South Africa is the most unequal country in the world. More than half of the country’s population still lives below the poverty line, while the majority of the country’s wealth is still in the hands of an elite minority.

Melanie Samson, a senior lecturer of Human Geography at Wits University in Johannesburg, says the effect of the exclusion of the informal recycling community amid the country’s coronavirus response is devastating.

“Reclaimers are faced with a deadly choice – stay at home and watch their children starve, or keep salvaging and risk contracting the virus. When they go out to work, they are also in danger of being beaten and arrested by police and security. But they don’t have any other options.”

She says only 10.8 percent of urban households in South Africa separate their waste. As reclaimers cannot collect, all of these potentially recyclable materials are being buried – making this a social and environmental crisis.

“Reclaimers are part of the essential waste management service,” argues Samson. “It does not make sense to exclude them.”

A supporter of ARO, Samson last year led a national stakeholder process to develop the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries Guidelines on Waste Pickers Integration for South Africa in 2019.

“Existing government policy on waste and recycling has not acknowledged reclaimers’ role in the sector. Recycling policy has been designed as if they don’t exist, but this will change with the Guideline,” she says.

Samson notes that the guideline includes agreements to respect reclaimers’ contributions and pay them, but adds that it has not yet come into effect.

Ncube and Hlatsawayo have the same requests. They want to continue working, but they require essential services permits to protect them from law enforcement. They also call for their labour to be acknowledged as essential and be remunerated for it. Municipalities should also provide them with masks and gloves, and their communities should be given sanitisers and washing stations, they say. Such requests are in line with demands from the Global Waste Pickers Alliance that brings together informal recyclers across the world.

On April 3, Barbara Creecy, South Africa’s minister in charge of environmental affairs, announced that her department had submitted a proposal to include waste pickers in the national Solidarity Response Fund, a scheme designed to support the most vulnerable during the coronavirus crisis.

The ministry on Wednesday also announced that it would begin the distribution of food parcels to waste pickers as part of the government’s coronavirus relief plan.

“As the collection of recyclables has not been included as an essential service, the consequence of this is that waste pickers are unable to work during the lockdown period. As a result, hundreds of waste pickers are currently experiencing situations of extreme hardship,” Creecy said.

Samson says such support is crucial to show the government’s growing commitment to reclaimers. But, she adds, the challenges that reclaimers are facing are not the result of coronavirus.

“They are the result of waste management policy that mimicked interventions in developed countries and ignored reclaimers. Reclaimer integration is crucial, so that reclaimers’ roles won’t be questioned in the future.”