Killings of Colombia ex-FARC fighters persist amid peace process

Since FARC fighters disarmed in 2017 as part of the peace deal, a total of 253 have been killed, including four already in 2021.

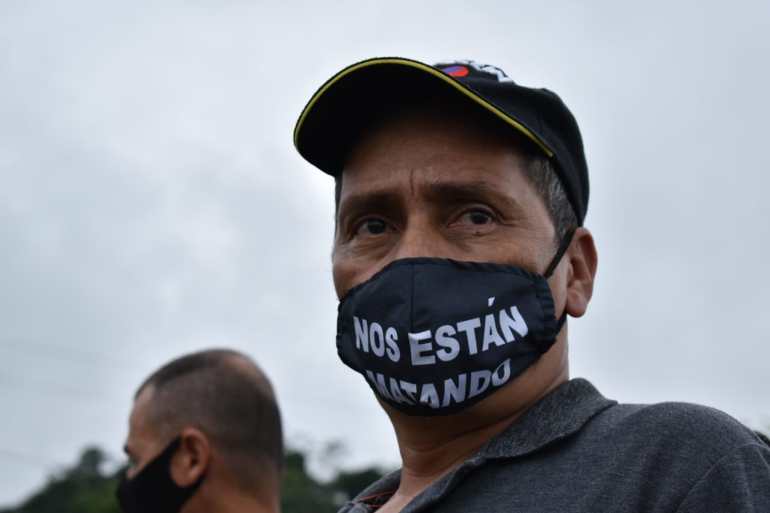

Since demobilising in 2017, former rebel fighter Manuel Antonio Gonzalez has faced numerous death threats and lost his son in a bloody murder.

Part of the now-defunct Marxist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebel group, who signed a peace deal with the government of Juan Manuel Santos in 2016, Gonzalez, 54, lives in worry, not only for his own life but for the thousands of other former fighters who signed up to the agreement alongside him.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInmates killed in Colombia riot shot intentionally: HRW

Four years after FARC peace deal, Colombia grapples with violence

‘The fight continues’: Colombia protests persist despite pandemic

The FARC, who have been accused of serious war crimes, handed more than 7,000 weapons to a UN peace mission in 2017, ending a five-decade-long conflict that left 260,000 dead.

Since the deal, 253 former fighters have been killed, according to numbers compiled by the Institute for Development and Peace Studies (INDEPAZ). It is unclear who the perpetrators are.

The current right-wing government of President Ivan Duque Marquez – which came to power in 2018 – has unsuccessfully fought to change the peace deal’s lenient punishments for former FARC fighters.

It blames dissident groups and drug gangs for the killings, while the ex-fighters blame state actors and paramilitary groups.

“They’ve killed four already this year, it’s very concerning,” said Gonzalez, who joined the rebel group in 1991, he says, out of necessity when paramilitary groups were taking control of the area where he lived.

Gonzalez is now based in Medellin and works as a coordinator for the FARC political party. He frequently travels to the various former rebel communities around the Antioquia region, where he says 27 have been killed.

“We always knew peace wasn’t going to come easy, that it’d be a struggle,” he told Al Jazeera. “When we signed up, we never imagined something like this would happen … that they’d start killing us.”

Gonzalez’s 31-year-old son, who was in the FARC alongside him, was killed in December 2019. His body was found on a roadside, riddled with bullets.

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) repeated its call for more attention to the security issues affecting former rebels and human rights activists being killed in rural areas in a report (PDF) released this month.

Who is responsible?

One of the biggest challenges is identifying those responsible for the killings.

Tatiana Pradas, researcher at Bogota-based think-tank Ideas for Peace Foundation (FIP), says when the FARC left rural areas four years ago, the government failed to take control and put security measures in place.

“There are many areas facing very complex security issues, with disputes between various armed groups, some of them well-known, like the ELN (National Liberation Army), others are dissident groups, and others which are much more informal with drug trafficking structures, and other groups that even operate without names, that perhaps don’t have any political ties, but more related to illegal activities,” she told Al Jazeera.

“It makes it really difficult to attribute a killing of an ex-combatant to just one specific group.”

A government official rejected claims there was little impunity for the killings of former FARC members saying 50.2 percent of the 291 cases being investigated have “suspected” perpetrators.

Emilio Archilla, the presidential adviser for stabilisation and consolidation, said prosecution delays are because the cases “are very complicated”.

He said the military is constantly fighting criminal elements the government claims is responsible for the deaths of the former fighters, but was unable to name specific groups.

Archila told Al Jazeera the government has continually provided security in the reintegration camps where former fighters live, “which guarantees that there are no killings inside them”, and that there are plans to increase protection at the camps.

However, there have been at least three isolated cases of former fighters being killed on the grounds of reintegration camps, according to FIP.

The camps differ nationwide in their security protocols. Some have police and army forces based on site or nearby, while others have less protection.

Vladimir Rodríguez Valencia, high counsellor for Victims’ Rights, Peace and Reconciliation in the Bogota district, said if there were more political will, the government could identify the perpetrators.

“There are territories in Colombia ruled through economic interests, with mafias that mainly use violence as a mechanism to take territorial control. If the lack of determination continues on the government’s behalf to reinforce peace in Colombia’s rural areas, threats and killings will continue,” he said.

Rodríguez says the judicial system, the public prosecutor’s office and the government need to move faster with their investigations.

“We can’t allow ourselves to move backwards on a deal that meant the demobilisation of the oldest guerrilla group on the continent by allowing the continued killings and threats against these men and women who left behind their weapons to commit themselves to a democracy.”

Isolation

At the Pondores reintegration camp in Colombia’s arid northern La Guajira region, close to the Venezuelan border, Ricardo Bolaños, 66, says former fighters in the region receive constant threats.

“The worry got so bad over the Christmas period that many left and went to other areas and for those of us who are here, we protect ourselves by not leaving here and staying isolated.”

Bolaños says safety concerns mean former fighters barely leave the reintegration camps at all at the moment.

“What we have been hearing has awoken a lot of fear and worry. Here on the coast, four comrades have been murdered. A woman and three men,” he told Al Jazeera.

One of the most recent killings was of two women aged 17 and 22 on January 1, while leaving a New Year’s Eve party in the Antioquia region.

They were sisters, and one had been in the armed group. Another three former FARC members have since been killed in different parts of Colombia.

And some former fighters who decided to live independently of communal reintegration camps also face threats. Álvaro Guazá, also known as Kunta Kinte, is one of them.

“Reintegrating has been very difficult. You could even say it’s been a failure … our people have been killed, displaced and threatened,” Guazá said, from an undisclosed location somewhere in Colombia’s western Valle del Cauca region. He declined to identify where he lives for his safety.

“The current government is going to keep treating us like guerrilla fighters and not like people in a reintegration process. They will keep seeing us as their enemies.”

In August 2019, some prominent demobilised FARC leaders announced a new era of the FARC and a return to weapons.

“We have to ask ourselves why did these ex-combatants go back to arms? They didn’t see any commitment on behalf of the government!” Guazá said.

Gimena Sánchez-Garzoli, a human rights advocate at the Washington Office on Latin America, says security for the demobilised fighters is not a priority for the Duque administration.

“It [the government] is more concerned about how it is appearing to the international community than what it has actually done, or how things are really faring inside the country in terms of peace,” she said.

But ex-fighters like Bolaños and Gonzalez are holding steadfast to their hopes for a more equal and peaceful Colombia.

“I’m still very optimistic in spite of everything right now. I’m going to keep moving forward with peace, because it’s what Colombia needs,” Gonzalez said.

“I think if there is a change in government … I’m not saying there needs to be a revolutionary president put in place, but just one that at least promises to move peace forward and one that is willing to reinitiate talks with other groups, so that there’s real peace, one with social justice.”