US eyes ‘aspirational’ refugee resettlement goal

The Biden administration says it is working to rebuild the refugee resettlement system, which was gutted under Trump.

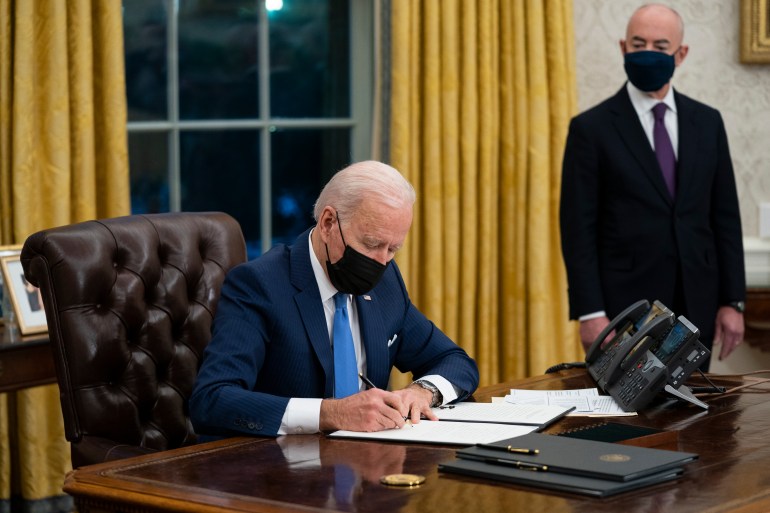

Washington, DC – Making good on a campaign promise, President Joe Biden last week formally announced that the United States would allow up to 125,000 refugees into the country this fiscal year – doubling last year’s limit.

But whether the US will be able to meet this new raised cap is uncertain, resettlement agencies say, amid persistent backlogs, reduced capacity and restrictions on refugee eligibility imposed by the previous Trump administration.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsUS Democrats’ bid to reform immigration laws blocked in Senate

Biden administration faces ‘critical moment’ on migration

“It will be a real challenge to reach 125,000,” said Melanie Nezer, senior vice president for public affairs for HIAS, one of nine refugee resettlement agencies in the US.

Only 11,411 refugees were resettled in the US during the 2021 fiscal year, according to the State Department – far fewer than the 62,500 cap the Biden administration set in May.

It also marked the lowest refugee resettlement figure since the programme was created in 1980. Under previous administrations, the US settled on average 95,000 refugees per year, refugee agencies say.

The Biden administration said it is working to rebuild the system, which was severely diminished under former President Donald Trump, who made reducing immigration one of his top goals. Trump set a refugee resettlement cap of 15,000 for the 2020 fiscal year – an historic low.

Officials also blamed the coronavirus pandemic, saying it restricted travel, as well as the ability to safely interview resettlement applicants.

“We are working expeditiously to rebuild processing capacity next fiscal year and are planning a robust resumption of interviews using a combination of in-person and video circuit rides,” a Department of State spokesperson told Al Jazeera in an email.

“We remain constrained by COVID, but we have adjusted and we expect to see arrival numbers continue to reflect our increased efforts.”

‘Depleted pipeline’

Experts have pointed to additional screenings introduced in 2017 by the Trump administration, dubbed “extreme vetting”, that forced applicants to provide extra documentation and included social media screenings, as part of the reason for delays in processing applications.

“The previous administration, in addition to setting consecutive historic low caps, also through measures such as ‘extreme vetting’ dramatically slowed down the process itself,” said JC Hendrickson, senior director of refugee and asylum policy and advocacy at the International Rescue Committee (IRC), another resettlement agency.

“What the Biden administration was confronted with when they took office was a depleted pipeline – they weren’t refugees moving through the process at a rate that made it feasible to hit a higher goal,” Hendrickson said.

According to the New York-based International Refugee Assistance Project, the measures had a harsh effect in particular on Muslim refugees, whose applications were stuck for months or even years in the security checks portion of the process. Muslim applicants also were disproportionately subject to “discretionary denials”, which blocked them from being resettled.

Krish O’Mara Vignarajah, president and CEO of Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, another resettlement agency, said more than 100 offices across the entire resettlement network closed down under the Trump administration. The organisation is now working with the Department of State to reopen them and has rehired staff that were furloughed.

“Despite the decimated refugee resettlement infrastructure that the Biden administration inherited, responsibility now sits with the new administration,” O’Mara Vignarajah said.

The total number of refugees admitted to the US every year, as well as the number of slots set aside for refugees from five regions of the world, is determined by the president, in consultation with Congress.

Under the 2022 allocation, 40,000 slots would go to people from Africa; 35,000 to the Near East and South Asia; 15,000 to Latin America and the Caribbean; 15,000 to East Asia; 10,000 to Central Asia, and 10,000 are set aside for emergency situations.

In its report to Congress, the Biden administration said individuals from Central America, Afghans with links to the US, LGBTQI+ refugees, Uighurs, dissidents from Myanmar and Hong Kong activists were priorities for resettlement. The administration is requesting $1.7bn for refugee resettlement in 2022, according to the report, up from $966m last year.

Discretionary criteria

But despite committing to resettling more refugees this year – the Biden administration’s cap is 15,000 more than the one set by the Obama administration in 2016 – as well as making an effort to resettle especially vulnerable groups, critics have said that the Biden administration has struggled to put together a coherent immigration policy overall.

In April, Biden signed an order that kept Trump’s 15,000-slot limit on refugee resettlement, arguing it “remains justified by humanitarian concerns and is otherwise in the national interest”. He raised the limit a month later after an intense backlash from refugee advocates and some Democratic officials.

Last month, amid a 20-year high in the number of migrants arriving at the US’s southern border with Mexico, nearly 15,000 Haitians gathered under a bridge in south Texas hoping to claim asylum. The US responded by emptying the camp and expelling more than 7,000 to Haiti, a nation reeling from poverty, gang violence and political instability.

The swift deportations were made possible by Title 42, a Trump-era health order that cited the need to protect the nation from the spread of the coronavirus to effectively block asylum at the border. Despite repeated calls from immigration advocates to reverse the measure, which they argued is unlawful and puts people in danger, the Biden administration has kept Title 42 in place and has continued to expel the vast majority of those arriving at the border.

Asylum seekers arriving at the border and refugees abroad arrive in the US under separate programmes. But observers say the treatment of migrants at the US-Mexico border differs greatly from the treatment Afghans who fled amid the fall of Kabul to the Taliban received in August – and runs counter to an overall commitment to resettle more refugees in the US.

“At the border, they are trying to deter people and prevent them from applying for asylum, claiming that due to COVID and due to resource constraints we can’t accept them into our system,” said Theresa Cardinal Brown, managing director of immigration and cross-border policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, a think-tank in Washington, DC.

“And yet we admitted 50,000-60,000 Afghans who had not been tested for COVID and surged resources to bring them in and process them into the United States,” Cardinal Brown told Al Jazeera. “So clearly, there is capacity in the system somewhere, but they are choosing to allocate it into some places and not others.”

Ultimately, Cardinal Brown said the 125,000-refugee cap is “aspirational”, meant to demonstrate the administration’s commitment towards refugees and to increase resettlement funding.

‘A real opportunity’

For her part, Nezer at HIAS said the fact that Afghan migrants are already on US army bases awaiting processing highlights the urgency of having innovative, efficient systems in place and could “jump-start” the refugee resettlement programme.

Many of the 53,000 Afghans who have been moved to eight US military bases were flown in on emergency flights amid the US’s hurried withdrawal from Afghanistan. They came into the US on “humanitarian parole”, a discretionary criteria the US uses in emergency situations. Another 18,000 are currently on US military bases overseas.

Congress in September approved $6.3bn in emergency assistance to help resettle Afghans, who have also been made eligible for some of the same benefits as refugees, such as housing assistance and help with finding jobs.

“It’s a real opportunity,” said Nezer, adding that also critical is leaders’ messaging around what refugee resettlement is and why it is important.

“We would like to see President Biden and others in the administration really articulate the case for refugee resettlement: saving lives, building communities, enriching our own communities with people from all over the world who are resilient and work hard.”