Nagaenthran case puts Singapore’s death penalty in spotlight

Malaysian with intellectual disability remains on death row after positive COVID test, as campaign for a reprieve captures public attention.

Singapore – Nagaenthran Dharmalingam remains confined to a cell in Singapore’s Changi Prison, living on death row as he has been over the past 11 years.

This week was set to be his last, but an eleventh hour stay of execution and the discovery of a positive COVID-19 test, kept him alive — for now.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsSingapore urged to halt execution of mentally-impaired man

Singapore to investigate ‘unusual’ surge in COVID-19 cases

‘Hard choices’ for Singapore media after controversial law passed

His story has caused ripples in the tiny Southeast Asian city-state, intensifying the debate around the death penalty in a country famed for its no-nonsense approach to crime.

In 2009, aged 21, Nagaenthran was caught trying to enter Singapore with just under 43 grams of diamorphine (heroin) strapped to his thigh. A year later, he was sentenced to death.

Nagaenthran claimed he was coerced into carrying drugs, although he later said that he acted as a mule because he needed the money.

His legal team has argued that his low IQ of 69 indicates an intellectual disability, affecting his ability to make informed decisions.

The case has provoked widespread international condemnation from human rights groups to representatives from the European Union and British entrepreneur Richard Branson.

There was even a rare intervention from the Malaysian Prime Minister. Ismail Sabri Yaakob penned a letter to his Singaporean counterpart Lee Hsien Loong, seeking leniency, according to Malaysia’s state news agency Bernama.

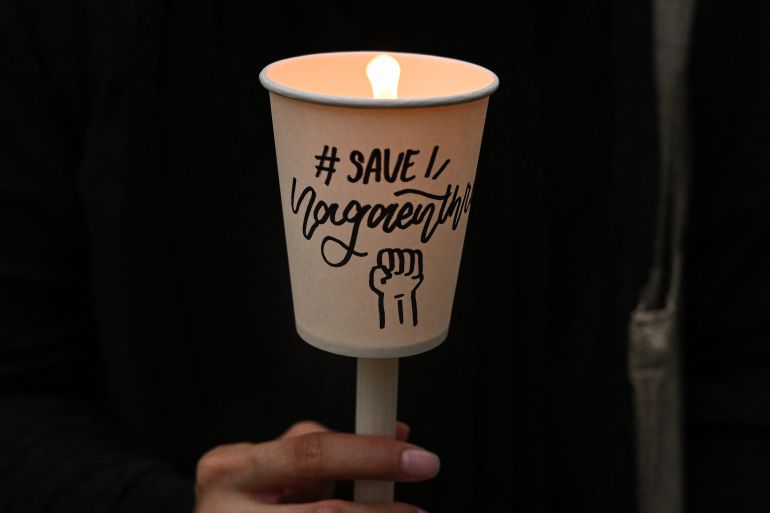

The plight of Nagaenthran has also generated rare criticism within the city-state itself. A petition started by a Singaporean to halt the execution has received more than 80,000 signatures.

Singapore has previously seen support for the death penalty. A 2019 survey by the Institute of Policy Studies of 2,000 residents found 70 percent agreed that execution was more of a deterrent against serious crime than a life sentence.

But this case has reignited the debate about Singapore’s death penalty.

“There are a few factors of Nagen’s case that catch people’s attention and garner sympathy,” said local activist Kirsten Han.

“The fact that he has an IQ of only 69 and other cognitive impairments, and yet has still been sentenced to death with his execution scheduled, is really alarming.”

‘Criminal mind’

Intricate details of Nagaenthran’s case have been shared and scrutinised online. In Singapore, outrage against death penalty cases is usually confined to fringe activist groups, but this story has gone mainstream.

High profile social media accounts shared photographs of the letter sent to Nagaenthran’s family in Malaysia by the Singapore Prison Service.

It briefly outlined when their son would be executed, before providing a stream of information about the logistics they need to sort in order to enter Singapore during the pandemic including quarantine procedures.

“I’ve met people who expressed shock by how cold the notice of execution to the family was. But that’s actually the standard way that such notices are delivered to families.

“The only difference with Nagen’s family is that the letter was longer because they had to include COVID regulations,” Han explained.

Singapore has a zero-tolerance attitude towards drugs, and anyone caught carrying more than 15 grams of diamorphine may face the death penalty.

There was, however, a slight relaxation of the rules in 2012. The Misuse of Drugs Act was amended, giving judges the opportunity to replace the death penalty with life imprisonment with caning in specific cases.

One of these technicalities would allow for an offender to avoid execution if they are mentally disabled. It was on this point that Nagaenthran’s appeal was launched in 2015 and failed.

Stephanie McLennan, Senior Asia Initiatives Manager at Human Rights Watch, told Al Jazeera that Nagaenthran received no “disability-specific accommodations” during his investigation and trial, a violation of international law.

But the defence of an intellectual disability has been disputed by the Singapore courts.

In a statement, Singapore’s Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) said: “He knew it was unlawful for him to be transporting the drugs, and he concealed the drugs to avoid it being found.

“Despite knowing the unlawfulness of his acts, he undertook the criminal endeavour so that he could pay off some part of a monetary debt. The Court of Appeal found that this was the working of a criminal mind.”

Little impact on criminal syndicates

If Nagaenthran is hanged, he will become the first person to be executed in Singapore since 2019.

Over the last eight years, 35 people have been killed by the state, according to Singapore government data. Twenty eight of them had been convicted of drug offences.

Singapore argues that its tough justice system makes it one of the safest places in the world.

Authorities say that drug traffickers are aware of the rules and given the risks faced, the quantity of illegal substances smuggled into the country is reduced.

Data from the MHA points to a 66 percent reduction in the average net weight of opium trafficked in the four-year period after the mandatory death penalty was introduced in 1990, for trafficking more than 1,200 grams of opium.

But the risk of death has not eliminated the illegal drug trade.

Last month, a Singaporean man failed in his appeal against a death sentence after he was caught smuggling one kilo (2.2 pounds) of cannabis into his homeland in 2018. And last year, another man was sentenced to death over Zoom for his role in a drug deal back in 2011.

The Singapore authorities may market the ultimate punishment as the ultimate deterrent, but anti-death penalty campaigners see things differently.

They argue that the death penalty punishes small players in a much larger game.

“Drug trafficking is still as prevalent in the region and Singapore is no different. Most of the executions witnessed over the years has largely been mules or trafficking in relatively minor quantities,” Dobby Chew, Executive Co-ordinator of the Anti-Death Penalty Asia Network told Al Jazeera.

“The syndicates behind the drug trade are still very much present and in operation even with multiple executions over the years.”

Campaigners are keen for Nagaenthran’s case to stay at the top of the news agenda, possibly acting as a catalyst for more support to abolish executions.

“First they tried to execute someone who is intellectually disabled. Now they are granting him some form of mercy and treating him for COVID-19,” said Chew.

“But for all we know, once he is cured, they’ll proceed with the execution. I think that the absurdity of the turn of events would force people to rethink what they know of the death penalty.”