Do check-out free stores spell end of British supermarket?

Tesco, the UK’s largest retailer, recently joined Amazon in offering a cashless, till-less experience.

London, United Kingdom – When Tom Cornall heard about the checkout-free Tesco shop opening near his office in London last month, he wanted to test it out.

“I tried to trick it,” he told Al Jazeera, after visiting the store the day it launched. “I picked up some stuff that I wasn’t going to buy, walked around for a bit, put it all back, and the system – the cameras and the sensors – they picked that all up, so they knew not to charge me for it … It was quite cool.”

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBrexit or pandemic? What’s behind the UK petrol crunch

As UK cracks down on protests, surveillance tech market grows

Don’t panic buy, Britain tells consumers

The scenes in GetGo, Tesco’s first and only such store, on High Holborn, central London, may appear futuristic, but they are a growing reality today.

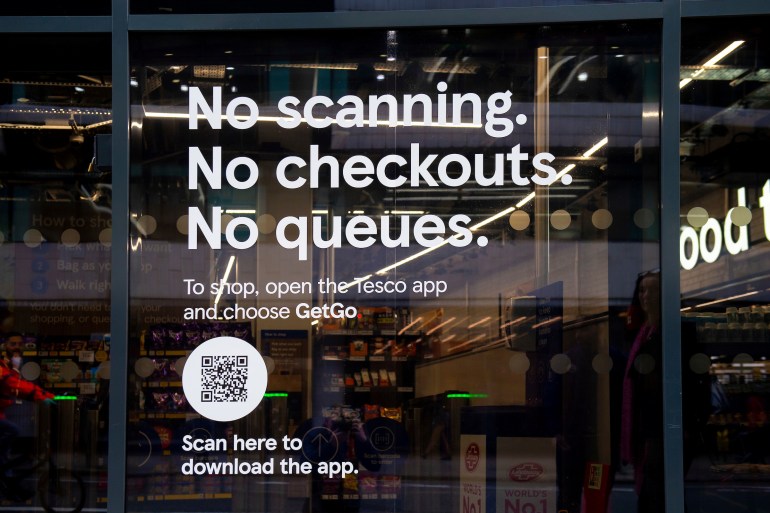

Download an app, scan a QR code to enter the store, walk through aisles full of sensors and cameras and you have now bought your groceries. No cash, card, or human interaction is necessary.

These are automated stores, without cashiers, checkouts or queues of the traditional kind. They look like any other small grocery supermarket, aside from the many cameras.

Tech behemoth Amazon has dozens, under the name Amazon Go in the United States, and six in the UK.

China and South Korea are no strangers to cashier-less stores and parts of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden have them too.

Now that Tesco, the UK’s biggest food retailer, has hopped on board, with rival retailers in the country such as Aldi, Morrisons and Sainsbury’s eyeing trials, could this be the end of the traditional British grocery shopping experience?

Not quite, say industry insiders.

“These are just trials at the moment,” Richard Lim, chief executive of the analyst group Retail Economics, told Al Jazeera, adding that retailers are building up a wealth of data to see just how aggressively they should roll out check-out free stores.

And they are unlikely to work everywhere, said Clare Bailey, independent retail expert at Retail Champion.

“It’s good for city centres where it’s quick in and out – you’re not bothered about talking to somebody,” she told Al Jazeera. “But in a big superstore or small market, you might prefer the human interaction.”

She said while new to customers, the technology has been in the works for the last 20 years.

“[The technology has] improved from where it was 20 years ago obviously … but it’s something that could have been done a long time ago. It is only now that businesses and retailers have decided that enough shoppers are willing to accept this kind of technology.”

The shift marks a dramatic change from the usual shopping experience.

The first British supermarkets opened in the mid-20th century, offering people the liberty to choose their own goods from shelves, rather than rely on counter service. Later, customers were able to scan their items, place them in a trolley and check out at a normal till.

More recently, self-checkouts have become ubiquitous, where people manage the entire process themselves, but are assisted by staff when needed.

During the pandemic, many have opted for click and collect or home delivery.

For Joshua Allerton, who owns Alleway’s, a small vegan confectionery in Birmingham, England, the latest “grab and go” model means better business all round.

Consumers have greater choices – they can enjoy the convenience of checkout-free stores, he explained, “but when they come into our shop, they’re going want that personalised experience that you won’t get at these [automated stores]”.

At his throwback shop, which is set in a redbrick building and sells everything from chocolate to popcorn, people often require assistance from a human – whether veteran vegans looking for new products, or people curious about veganism starting from scratch.

But Allerton said he has visited an Amazon Go in London, and as a consumer, found it extremely convenient.

Trigo, the Israeli startup providing the technology for Tesco’s GetGo, alongside many more globally, predicts a surge of its use, especially after the pandemic.

“Despite the convenience of click and delivery, people still prefer the tactile experience of touching and smelling their groceries,” a Trigo spokesman told Al Jazeera. “The health crisis has created intense pressure to implement technologies that will do away with lines and crowding.”

Tom Rebbeck, who recently visited Tesco’s checkout-free store, described it as rather mundane, but expects it will be a regular convenience soon.

Besides a few small differences, it was like being at any other Tesco shop, he said.

“It’s a bit like an Uber,” he told Al Jazeera, referring to the ride-hailing app. “You know, the first time you get out of an Uber, you kind of want to pay the driver and then you realise you don’t have to pay and then you get so used to it.”

“If you [go to these stores] five times, the idea of going to a normal store and queueing is gonna seem quite painful.”

While UK grocers are unlikely to go fully automated any time soon, there are concerns about the effect automation will have on the workforce.

In 2019, the UK’s Office of National Statistics (ONS) said supermarket cashier jobs are most at risk, with 65 percent likely to be replaced with automation.

But Lim said the industry is used to change, having experienced large reductions in the labour force in the last five to 10 years as national wages rose, which pushed up costs for many companies.

Bailey said the shift will usher in a movement of jobs, rather than job losses – with more people required to have specialised skills to install the cameras or programme the sensors.

Customer-facing roles, she said, will still exist, but in a different way, to help customers with any technological errors.

Data privacy concerns, analysts said, are unlikely to be a big issue.

Loyalty cards and schemes by grocers have been collecting the public’s data for years, said Bailey.

“There is a huge potential reputational damage that comes up,” Lim added, referring to data privacy breaches. “I don’t think that retailers will move into this … naively.”