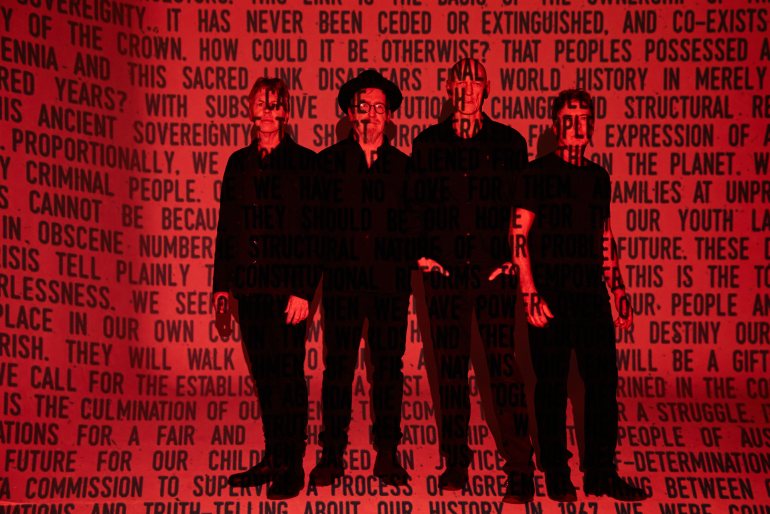

Midnight Oil project aims to put Indigenous voices centre stage

Veteran band working with Aboriginal performers to campaign for an Indigenous voice to Australia’s parliament.

Melbourne, Australia – Peter Garrett, the bald, two-metre-tall frontman of Australian rock band, Midnight Oil, has never had much difficulty attracting attention.

But now the outspoken former member of parliament is backed up by some of the strongest Indigenous voices in contemporary music on a new recording and tour – The Makarrata Project.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInspiring cultures: Bruce Lee’s Fist of Fury dubbed into Noongar

Thousands march in Australia for Indigenous recognition

Australian police under probe over arrest of Aboriginal teenager

The aim: to educate Australia about the Uluru Statement from the Heart, an advocacy campaign for a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous voice to Parliament.

“Music is the number one education in this country,” said Indigenous musician Bunna Lawrie who has joined Midnight Oil on the project. “Through music, young kids hear it and they learn a lot of things and they begin to understand.”

Indigenous and non-Indigenous musicians have been at the forefront of reconciliation for decades with Lawrie’s own band, Coloured Stone, getting together back in 1977 on Koonibba Mission in remote South Australia.

Using traditional instruments such as clap sticks and didgeridoo, along with electric guitars and drums, Indigenous bands such as Coloured Stone, No Fixed Address and the Warumpi Band caught the ears of mainstream city listeners in the mid-1980s.

“We love touring this beautiful country, it inspires me,” Lawrie told Al Jazeera. “It’s healing to be out here, when you’re singing songs to people. And it’s healing for the people who come to enjoy the music and to dance.”

The non-Indigenous, Sydney-based Midnight Oil would eventually tour remote Indigenous communities and collaborate with Indigenous bands, releasing Diesel and Dust, which became a global hit in 1987.

“So we’ve been doing this a long time, collaborations, since way back in the ’80s,” Lawrie said. “It’s a good relationship we build up as friends and musicians – non-Indigenous people and Aboriginal people in this country. That’s the way reconciliation should be, working together and working out things the right way.”

Voice to Parliament

Midnight Oil drummer Rob Hirst told Al Jazeera the Makarrata Project “develops many of the same themes originally explored” during the recording of Diesel and Dust and that the inclusion of an array of Indigenous artists has “lifted the songs to levels beyond anything we could have imagined”.

“Makarrata” is a complex Indigenous Yolgnu word which the text of the Uluru Statement refers to as “the coming together after a struggle”.

It is this concept that underpins the years-long advocacy campaign that seeks to embed a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous voice to Parliament, a campaign that Midnight Oil, Bunna Lawrie and other Indigenous artists are now encouraging Australians to support.

Pat Anderson – Co-Chair of the Referendum Council – told Al Jazeera that while a new idea, constitutionally enshrined Indigenous voice to Parliament was simply a continuation of centuries of Indigenous advocacy and struggle for justice.

“We have been trying to right the wrongs and get justice in our own country pretty much since those first ships arrived,” she said, referring to the arrival of the British and the start of colonisation in 1770. “It is the latest attempt for the country, for Australia, to accept us and acknowledge us and give us our rightful place in this country of ours.”

Yet the legal process to embed an Indigenous voice in federal parliament requires constitutional change which can only come via majority vote in a nationwide referendum.

As such, Anderson’s first challenge is to convince the government to hold a referendum, and then to encourage Australians to vote positively for an Indigenous voice to Parliament.

The Uluru Statement was delivered in 2017 after years of consultation by the Referendum Council. It puts forwards the aims of the Council, which includes the voice to Parliament, which would be an advisory committee separate from the government to advise Parliament on issues affecting Indigenous Australians.

“We want a constitutionally enshrined voice so we can speak with some power and have some authority and speak directly to the parliament about our needs and about everything that affects us,” she said.

“This type of consultation has never happened before in this country. And out of this process came the Uluru Statement from the Heart.”

Anderson said that it was necessary to enshrine such a voice to Parliament in the Constitution, so that it could not easily be legislated out of existence.

The Australian Federal Parliament has previously attempted to create a formal political process to represent Indigenous peoples by way of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC).

Being only legislatively, and not constitutionally, empowered, ATSIC was abolished in 2004 amid claims of corruption.

Precedent

Yet Australia does have a positive precedent for constitutional change in matters concerning Indigenous people.

In 1967, an overwhelming majority voted “yes” for constitutional amendments that would count Indigenous people as citizens of the country and allow the federal government to make laws that would affect Indigenous communities.

While the 1967 referendum set an encouraging precedent, getting Australians to vote positively for a permanent advisory voice to Parliament might prove challenging, especially when Malcolm Turnbull who was prime minister in 2017 when the idea was proposed, immediately shut down the discussion, labelling the plan a “third chamber” of government.

Anderson argued the prime minister’s description was “scandalous” and while Turnbull recanted on that later, “the damage was already done.”

“[Turnbull] refused the Australian people to even have a conversation,” said Anderson. “What arrogance is that?”

While the Uluru Statement has faced opposition from within the government, it has also drawn criticism from the Indigenous community.

Approximately 30 dissenters walked out of the final meeting in 2017, after which the Uluru Statement was released.

They criticised the consultation process and questioned why Indigenous people’s rights should come through a colonial constitution as opposed to a treaty.

An official statement released by the Aboriginal Embassy in Canberra stated, “The proposed Makarrata agreement-making is about domestic contracts, which will keep First Nations under a colonial constitution’s head of power.”

The statement also questioned the use of the term “Makarrata”, stating that “the deep meaning of Makarrata is misunderstood” and noting the use of the term had been “strongly rejected” during the National Aboriginal Conference (NAC) Treaty consultation process in the 1980s.

However, despite the criticism and the challenges, Anderson remains optimistic about the new initiative and said the support shown by the array of Indigenous and non-Indigenous musicians is “fantastic”.

Midnight Oil released the Makarrata Project “mini-album” in October 2020, the band’s first new music release in two decades, and plans to tour the project during March.

“[The music is] just so upbeat and so powerful and so energetic – how could you not be moved?” she asked.

For Bunna Lawrie, the recording and the shows present an opportunity for Australian audiences to hear directly from the voices of Indigenous people which he said is vital to reconciliation.

“Please come out and talk to us and listen to our stories,” he told Al Jazeera. “When you start talking to people it changes [things].”