What prompted India-Pakistan ceasefire pact along Kashmir border?

Politicians and experts reflect on reasons that made the two nations agree to a rare reaffirmation of a 2003 ceasefire along the disputed border.

New Delhi, India – For nearly two weeks now, a tense silence has prevailed over the skies of Jura, a small village less than a kilometre away from the Line of Control (LoC), the de facto border that divides Pakistan-administered and Indian-administered Kashmir.

The village, located in the region’s Neelum Valley, has long been in the firing line of hostilities between the two nuclear-armed neighbours, who have traded frequent small-arms, mortar and artillery fire across the LoC for years, resulting in dozens of casualties on both sides.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Repeat of what happened in Myanmar’: India detains 160 Rohingya

100 days and 248 deaths later, Indian farmers remain determined

Kashmiri man demanding son’s body charged under anti-terror law

Last month, there was a rare thaw in the otherwise frozen relations between the two countries as their armies announced a sudden and rare reaffirmation of a 2003 ceasefire agreement, pledging to bring a halt to violence that killed at least 74 people in 2020 alone.

Since then, residents of Jura say the guns have fallen silent, although they are not sure if they trust how long the newly established, fragile peace will last.

“Yes, [the firing] is finished for now, but we don’t know anything about the future,” said Faisal Siddiq, 16, whose home was badly damaged in a round of shelling last year.

“We don’t know anything at the moment, and we don’t have much trust [in the ceasefire].”

‘A good beginning’

Pakistan and India, however, say they are committed to the ceasefire, while analysts suggest it could be the start of a thaw in relations.

“In the interest of achieving mutually beneficial and sustainable peace along the borders, the two [Directors General of Military Operations of India and Pakistan] agreed to address each other’s core issues and concerns which have the propensity to disturb peace and lead to violence,” reads a joint statement issued by India and Pakistan on February 25.

Both India and Pakistan claim the disputed Himalayan territory of Kashmir in full, but administer separate portions of it, divided by the LoC.

In Indian-administered Kashmir, where the majority of Kashmiris reside, the development was welcomed by leaders across party and ideological lines.

“I think this is a good thing, at least there will be some peace on our borders,” said Farooq Abdullah, a senior politician in Indian-administered Kashmir and current member of India’s Parliament, calling the development “a good beginning”.

“People on both sides of the border are suffering, dying, people can’t cultivate their lands, homes are being destroyed.”

Abdullah hoped the India-Pakistan ceasefire deal would lead to a broader settlement of issues between the two countries, particularly on Kashmir.

Mehbooba Mufti, a patron of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) and former chief minister of Indian-administered Kashmir, also welcomed the announcement.

“It’s a welcome step because people on both sides of the border are the sufferers,” she told Al Jazeera, adding “some kind of a political initiative” should follow the move.

“If the SAARC [South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation] summit is [held] in Islamabad, I hope [Indian] Prime Minister [Narendra Modi] visits.”

Mufti said the original 2003 ceasefire agreement was followed by direct dialogue between the two countries, as well as an internal dialogue between the Indian government and Kashmiri separatists, a move she would like to see repeated.

“[T]hat is why that was a successful ceasefire and also it had a very positive impact on the situation inside Jammu and Kashmir – militancy came down because there was a dialogue between [then-Pakistani President Pervez] Musharraf and [then-Indian Prime Minister Atal Behari] Vajpayee,” she said.

2003 ceasefire agreement

The ceasefire was initially established in November 2003 in order to stabilise the situation at the de facto border between the two countries in disputed Kashmir.

While it was initially accompanied by a number of positive developments, including the resumption of bus and trade links between the two sides of Kashmir, it was frequently violated in the years to come.

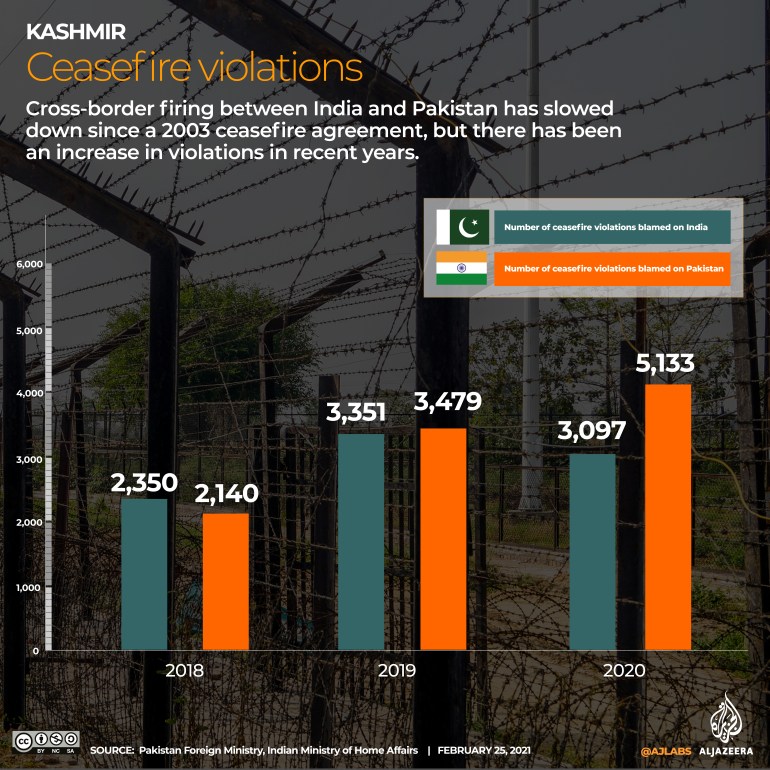

Since 2017, firings at the LoC by both the sides have intensified significantly, the data shows.

India’s government says Pakistan violated the ceasefire at least 5,133 times last year, killing 22 civilians and 24 security personnel.

Pakistan, on its part, says India violated the ceasefire at least 3,097 times in 2020, killing 28 civilians and wounding 257 others.

Relations between the two countries have deteriorated sharply since February 2019, when India blamed Pakistan-based armed groups of carrying out an attack in the Indian-administered Kashmir town of Pulwama that killed more than 40 Indian security forces.

Pakistan has denied the allegations.

When India carried out retaliatory air attacks a few days later, Pakistani jets also scrambled to carry out similar raids near military installations in Indian-administered Kashmir.

Tensions cooled after the pilot of an Indian fighter jet shot down by Pakistan in the aerial skirmish was returned two days later.

But there have been no direct talks between the two sides since, with both nations frequently accusing the other of supporting armed groups.

Relations soured further in August 2019 when India revoked a special constitutional status granted to Indian-administered Kashmir, a move Pakistan said was in contravention of United Nations Security Council resolutions on the decades-long dispute.

What prompted the rare move?

Given the virtually frozen relations, what prompted the sudden thaw that led to a reaffirmation of the ceasefire?

For Tirumallai Cunnuvakum Anandanpillai Raghavan, a former Indian High Commissioner to Pakistan, the thaw is the result of a natural cycle in relations between the two countries.

“In my view, the reason why this step was taken is that both countries derive that prolonged instability is not in either’s interest,” Raghavan told Al Jazeera. “I don’t see the role of any extraneous factor in this directly.”

Pakistan’s official stance on the issue seems to echo this view, with Pakistani Foreign Ministry spokesman Zahid Hafeez Chaudhri saying the move was taken to de-escalate the violence.

“The agreement will help save Kashmiri lives and alleviate the suffering of the Kashmiris living along the LoC,” he said at a weekly press briefing last week.

“We have […] maintained that escalation along the LoC is a threat to regional peace and security. The recent development is very much in line with Pakistan’s consistent position.”

Chaudhri said Pakistan had “never shied away from talks and has always called for peaceful resolution of all outstanding disputes, including the internationally recognised dispute of Jammu and Kashmir”.

A Pakistani national security official, meanwhile, said the reaffirmation of the ceasefire was a positive development but warned the gains were fragile.

“It is surely a positive development because ceasefire violations by India were resulting in the loss of civilian life and property,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity given the sensitivity of the subject.

“We hope that this stays for the sake of the people along both sides of the LoC.”

The official said Pakistan remained committed to its existing position on the Kashmir dispute. “Our security perspective in the region is one of economic security,” he said.

Mufti, the political leader in Indian-administered Kashmir, however, believes the “global situation” may have had a role to play.

“There is a new [presidential] administration in [the United States of] America now,” she said. “They want to do things in a different way than what [former President Donald] Trump wanted.

“Also, India wants to be a player in the global world and I think, somewhere the Kashmir issue is kind of holding it down. I think the ceasefire is the bare minimum that they could agree with Pakistan.”

Washington, DC-based regional analyst Michael Kugelman, however, concedes that while the development benefits the US, it may not have been directly affected by US President Joe Biden’s new administration.

“I don’t anticipate that pressure from the Biden administration was a factor, given that the negotiations leading to the accord began well before the administration took office,” he says. “That said, let’s be clear: Washington benefits in a big way from this ceasefire.

“Pakistan will now be less distracted by India and will be better placed to help Washington with the peace process in Afghanistan. And India will be better placed to focus its attention on the China threat that drives US-India partnership. So while Washington may not have been a factor in this story, it certainly is advantageous by the outcome.”

New Delhi-based defence analyst Ajai Shukla sees the announcement as a consequence of “Pakistan choosing a moment of Indian vulnerability against China, to make an offer that would convince India of Pakistan’s bona fides”.

“Islamabad hopes that the timing of its offer persuades New Delhi of Pakistan’s genuine desire for a workable arrangement in Kashmir,” he said.

Raghavan, meanwhile, stressed that the agreement was “a limited one”, aimed only at “maintaining the 2003 ceasefire, reinforcing it and reasserting it”.

“Now, what are the next steps that will follow, it is too early to say because relations have gone through such a bad period,” he said. “One has to be mindful and not be excessively optimistic or excessively pessimistic.”

With additional reporting by Al Jazeera’s Asad Hashim in Islamabad, Pakistan.