‘Little hope left’: Lebanon’s paralysis and a collapsing state

International community fails to speed up government formation in Lebanon, even with the economy in meltdown.

Beirut, Lebanon – Lebanon has been without a fully functional government for almost 10 months, with President Michel Aoun and returning Prime Minister-designate Saad Hariri unable to agree on a cabinet.

Disagreements focus on the number of ministers and how they will be allocated based on sectarian and political representation. The two have been unable to settle their differences, having met 18 times since Hariri’s appointment in October.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFrance warns Lebanon’s leaders against ‘collective suicide’

Turkey’s Karpowership shuts down power to Lebanon

Lebanon’s FM asks to quit after ISIL comments anger Gulf states

Hariri and his political party, the Future Movement, insist they are pushing for a technocratic government that focuses on reforms.

“They [Aoun and allies] want a government that they can control and have veto power,” MP Mohamad Hajjar of the Future Movement told Al Jazeera. “Hariri’s government of experts has sectarian balance and representation of Muslims and Christians, but they want a government based on quotas.”

Meanwhile, Aoun and his Free Patriotic Movement Party say they do not want veto power but a more representative government.

“It has become evident that prime minister-designate is unable to form a government capable of salvation,” Aoun said in a letter to parliament his office delivered last week. “He is making it [Lebanon] a captive as he traps the people and government and takes them as hostages driven into the abyss.”

The president’s office was unavailable to comment to Al Jazeera.

Political paralysis is not an uncommon event in Lebanon, a country with a delicate sectarian power-sharing system. It was once without a president for almost two and a half years until Aoun came to power in late 2016. But things are far more different than they were back then.

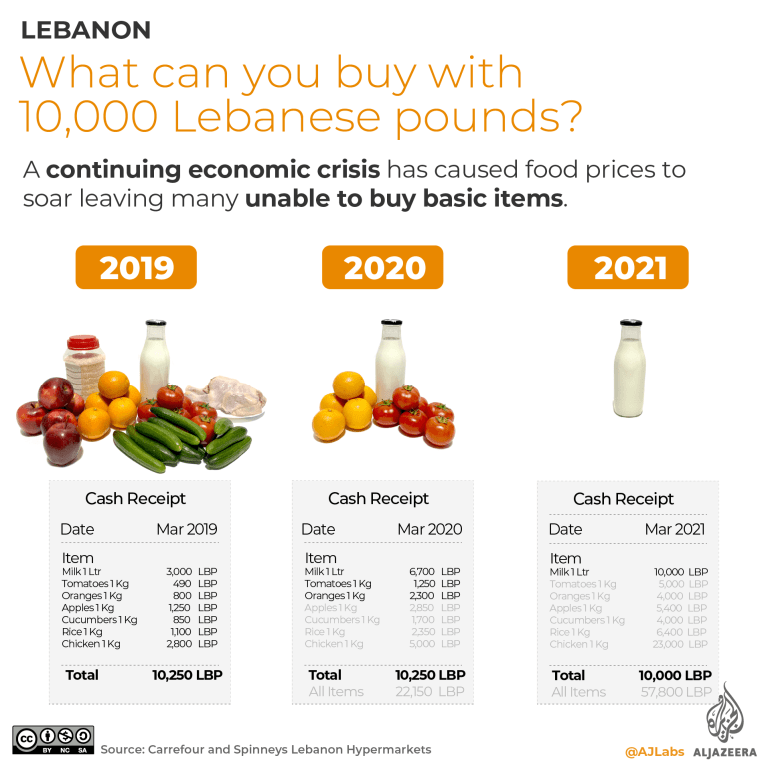

Lebanon today is reeling from a crushing economic crisis that pushed more than half its population into poverty. On top of having to cope with a local currency that has lost more than 85 percent of its value in just over a year, people also struggle to afford basic food items that have become 400 percent more expensive.

In 2020 alone, Lebanon witnessed the freefall of its currency, the COVID-19 pandemic further pulverising its economy. In August, the devastating Beirut Port explosion killed more than 200 people, wounded about 6,000 others, and flattened many of the capital’s neighbourhoods.

‘Very little hope is left’

With the country running on its last financial reserves, the international community promised support for Lebanon on the condition that it forms a government and enacts economic and structural reforms.

Over the past three years, states and international organisations have promised to provide Lebanon with billions of dollars in loans and aid to fix its poor infrastructure, rebuild the destroyed Beirut Port, and an International Monetary Fund programme to bail the country out of its economic woes.

The Office of the United Nations Special Coordinator for Lebanon told Al Jazeera in a statement the country’s rulers need to “put the interest of the country above political and personal agendas” to help steer it towards recovery.

“The biggest impact of this crisis is on the Lebanese people who are paying a high price,” the UN office said. “Very little hope is left for the population.”

Despite all this, Lebanon’s rulers have not budged. Aoun has implied that Hariri ought to resign several times, and some officials close to Hariri have hinted that the option is on the table.

“It’s a possibility but not a decision,” Hajjar said. “At the moment, he’s chosen to take the responsibility and commitment to a government.”

French ‘fiasco’

While the international community’s repeated statements and meetings with Lebanese officials have led to nothing, Lebanon’s former colonisers tried to be more proactive.

French President Emmanuel Macron jetted to Beirut several days after the port explosion in early August and offered humanitarian aid but conditioned it on structural reforms. Macron and other world leaders raised about $300m in humanitarian aid for the country.

Macron returned in late August, pushing for government formation and reforms before any assistance was doled out to rebuild the port and help its battered economy. He distributed a draft economic road map, often dubbed the “French initiative”, which included reforms such as restructuring the electricity sector, implementing a forensic audit of the central bank’s accounts, and a resumption of negotiations with the International Monetary Fund.

Lebanese authorities promised to commit to this plan. Macron and the devastating blast seemed to be a turning point, but it was not. By late September, France’s president accused the country’s leaders of “collective betrayal”, and gave them six weeks to implement the French initiative. That did not happen and even France’s travel restrictions imposed on Lebanese officials accused of obstructing government formation failed to work.

Joseph Bahout, director of the American University of Beirut’s Issam Fares Institute and a former consultant with the French foreign ministry, described the French initiative as “a failure, not a fiasco”.

“It left too much leeway to the Lebanese to spoil it,” Bahout told Al Jazeera, explaining that Macron initially called for a government of independent technocrats, later backtracking to settle with a government with wide political consensus.

“Not enough sticks, too many carrots,” said Bahout.

Many of Macron’s demands resonated with those of an angry population that tried to overthrow Lebanon’s ruling class in late 2019.

“When he [Macron] sat with Lebanese leaders, he started stripping conditions: ‘Early elections? We can keep that out. International inquiry on the port explosion? We won’t insist on it,’” Bahout explained.

‘System is dead’

Even at one of the most critical times in its short history, tiny, cash-strapped Lebanon’s rulers are ignoring the international community’s billions pledged in financial assistance, while continuing their political squabble.

But that just might be the nature of the country’s sectarian power-sharing system, which Lebanese American University professor of political science Bassel Salloukh said has “reached a dead end”.

“It’s ‘zombie power-sharing’; the system is dead but keeps going without the possibility of any reforms,” Salloukh told Al Jazeera. “No one wants to actually own up to the collapse or the kind of policies you need to undertake to respond to IMF and World Bank demands.”

It may just be political suicide for Lebanon’s ruling parties that dominated the political and economic landscape over the past few decades, which notably includes public-sector hiring and private contracting in exchange for political loyalty.

“The sectarian system is not made to reform itself, only to reproduce itself,” Salloukh explained. “Any decision to reform economically would torpedo the economy that has been built over the past 30 years.”