Poverty, stigma behind bodies floating in India’s Ganges River

Villagers along the river say cremation expenses rose during the pandemic, forcing many to immerse or bury the bodies in sand.

Lucknow, India – Virendra Kumar, a resident of Ajrayal Kheda village in Unnao district, about 520 kilometres (323 miles) from India’s capital New Delhi, says he had to bury the body of his dead son on the banks of the Ganges River instead of cremating him.

“My son Arun Kumar was 18 and was suffering from epilepsy since he was 10. He was sick and denied admission by a private hospital when he suffered a seizure,” the 54-year-old father told Al Jazeera, sitting outside his shanty hut in the village.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAs COVID overwhelms India’s hospitals, housing societies step in

India’s economy showed momentum in Q1 prior to COVID surge

Why is WhatsApp suing the Indian government?

“So we were getting him treated with a local doctor and the cost of treatment even locally was about 2,000 Indian rupees ($28) a month. Yet he breathed his last on May 9 at home.”

Kumar says with a family income of less than $100 a month, he did not have any money left to meet his son’s cremation expenses.

“Our main source of income is agriculture and all the savings were used in the marriage of my daughter. We are in debt as well,” he said. “We are Dalits, so you know how poor we are.”

The Dalit community, formerly referred to as the “untouchables”, is at the bottom of India’s complex caste hierarchy and has faced systemic marginalisation and oppression for centuries.

“My religion has the custom of burning the dead body and not burying it but it was my poor economic situation due to which I had to perform the burial. The funeral would have required at least 15,000 rupees ($200) but I did not have that money,” Kumar told Al Jazeera.

“I could not even do my son’s “Terahvi” (customary community lunch on 13th day of death) and only invited a couple of people from the neighbourhood. It’s eating me from inside.”

Kumar says he could not borrow any money from his friends because “everyone is under some financial stress due to the coronavirus lockdown”.

Hundreds of dead bodies were seen floating in the Ganges in the northern Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar after a ferocious second wave of the coronavirus pandemic hit India in April.

Mass burial sites were also found along the riverbank in Unnao and Prayagraj districts of Uttar Pradesh, as photos of semi-buried bodies, most of them wrapped in traditional saffron cloth, emerged on social media.

Cost of cremations up during COVID-19

At Bithoor near the main city of Kanpur in Uttar Pradesh, a holy site along the Ganges River where cremations are held, priest Rakesh Kumar Upadhyay tells Al Jazeera the cost of cremations has shot up during the pandemic.

He says there has been a sudden surge in the demand for firewood and other items required for Hindu cremation rituals.

“Earlier the price of four quintal of firewood was 2,500 rupees ($35) but now the prices have doubled,” he says.

“On an average, a family has to spend 5,500 rupees ($75) for firewood. Then other materials such as shroud, sugar, incense sticks cost 1,500 rupees ($20) more. The cost of bringing the dead body either in an ambulance or a tractor is minimum 1,000 rupees ($14). So the cremation now costs an average of 8,000 rupees ($110), while in the month of March it was just 5,000 rupees ($69),” the priest added.

As images of floating and buried bodies in the Ganges triggered outrage, several districts capped the cost of ambulance services, firewood, and in some areas, even the cost of cremating people who had died from COVID-19.

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath ordered the state officials to hold cremations “with utmost dignity”.

“No one should be allowed to dispose of bodies in rivers due to religious traditions,” he said, adding that a fine could be imposed to prevent the dumping of dead bodies in the rivers.

But there are other cremations costs too, according to Upadhyay.

“The other costs involved in cremation are the fee of the priest, the fee of the person who sets the pyre but these have not been fixed by the government and people pay according to their paying capacity.”

Upadhyay says poor people had to resort to either burying or submerging the dead bodies in the river due to the cost.

“From Kanpur in central Uttar Pradesh to Ghazipur in eastern Uttar Pradesh, a lot of dead bodies have been buried on the banks of Ganges,” he says.

“Digging a grave in sand takes nothing but labour of an hour.”

Denied firewood for husband’s cremation

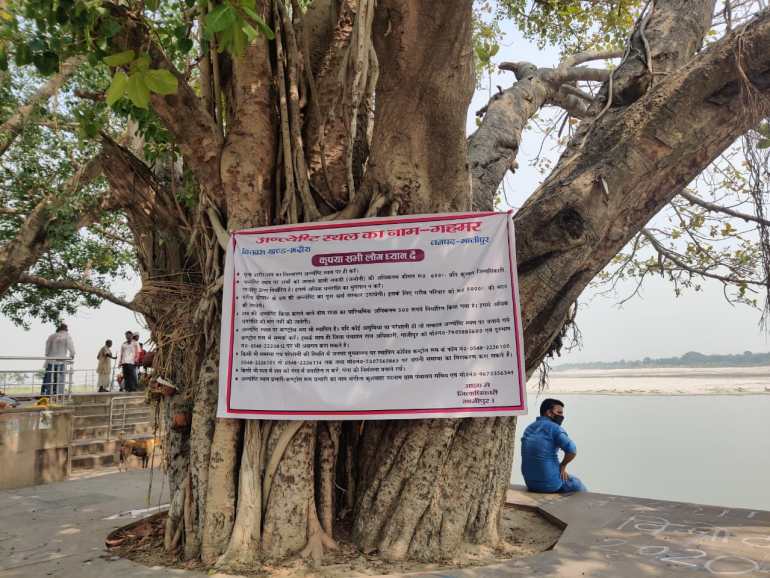

On the Narva Ghat (river bank) on the Ganges in Ghazipur district’s Gahmar village, a banner hangs on a banyan tree.

“No one will immerse dead bodies in the river and the price of firewood has been capped at 650 rupees per quintal ($9). The administration would bear the cost of cremation in case the family is financially weak,” it says.

In the district which shares its border with Bihar state, 32-year-old Kavita Devi is mourning the death of her husband who died of “COVID-19-like complications” on April 24.

“We had to immerse my husband’s dead body in the Ganges because we were denied firewood,” the mother of three told Al Jazeera.

“We were already in financial crisis because all the money was spent on the funeral of my brother-in-law who passed away a day before.”

Kavita said her younger brother-in-law, father-in-law and other relatives decided to take the body to the riverbank and submerge it in the river. Her husband was a mason by profession and the sole bread earner for the family of five.

Durga Chaurasia, the former village council head at Gahmar, says more than two dozen people died in the village after falling sick.

“A lot of people immersed the dead bodies in the river because of their poor financial condition,” he told Al Jazeera.

‘Villagers opposed cremation’

Soni Kumar, a resident of Raniganj in Bihar state’s Araria district, says she had to bury the bodies of her parents in the field after the villagers opposed the cremation of her parents due to the fear of catching COVID-19.

Soni, 18, lost her father on May 3 and her mother four days later.

“We had take some loans for the treatment of my father because of which we had to discontinue the treatment of my mother,” she told Al Jazeera over the telephone.

“The sad part is no one from the village helped us in the cremation and they strictly opposed the burning of the bodies.”

Soni says she was able to dig the graves with the help of a distant cousin and perform the burials because the villagers feared burning the bodies would spread the virus.

“We have received some compensation from the government. This will of course help in paying the debt but my parents are now gone. We could not give them dignity even in death. This is painful.”