‘Obey the Party’: The CCP steps out of the shadows in Hong Kong

Once forced into a low-key existence, the Chinese Communist Party has become increasingly assertive in the former British colony,

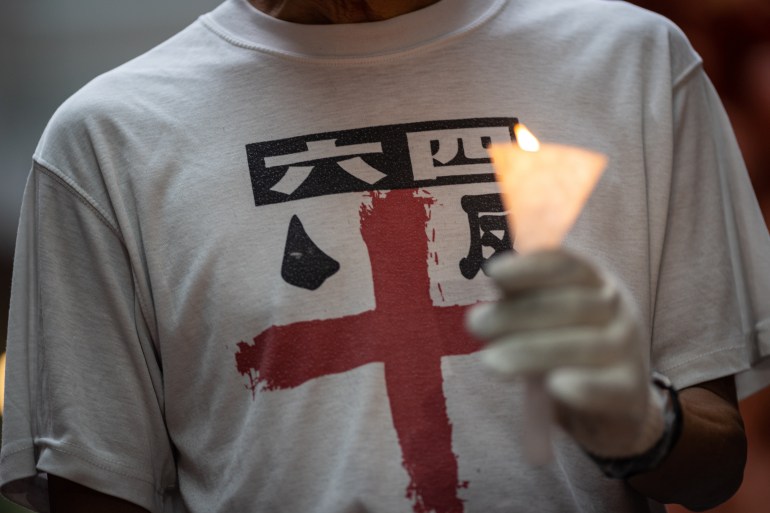

Hong Kong, China – It is the governing party that has remained an underground organisation even in part of its own territory, but as the Chinese Communist Party marks its centenary this week there are signs it is stepping out of the shadows in Hong Kong, the former British colony that became China’s most restive city.

What is more, the party – feared and loathed by many Hong Kong people – is demanding their love and absolute allegiance.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsHong Kong police arrest former Apple Daily journalist at airport

As China’s Communist Party turns 100, economic challenges loom

HK’s security chief promoted to No 2 job amid crackdown

“For the CCP, it’s paramount that the people in Hong Kong recognise China’s achievements under the party’s leadership,” said Bruce Lui, senior lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University and a veteran political commentator. “Anyone failing to do so falls short of loving the party and the nation.”

In early June, a formation of more than 350 people gathered in a Hong Kong public plaza to belt out the patriotic tune “No Communist Party, no new China” despite COVID-related restrictions on gatherings.

Then two weeks ago, a symposium on the party’s centennial at a heavily-guarded convention centre in the heart of the city was attended by the political elite, including chief executives past and present.

And on a weather radar at one of the territory’s highest points, the slogan “Obey the party” looms over the skyscrapers below.

Over the past few years, the CCP has been assuming an ever-higher profile in the former British colony and asserting its presence in a territory that was returned to Chinese rule in 1997.

For more than half of the last century, Hong Kong served as a sanctuary for generation after generation of mainland Chinese fleeing Communist rule.

First came the moneyed class, after the civil war ended in 1949 and the Communists took over from the nationalists who retreated to Taiwan. Industrialists from Shanghai and the nearby prosperous coastal cities as well as landowners and merchants moved south fearing the prospect of collectivisation.

The next to arrive were the intelligentsia, targets of political purges in the 1950s. Then came the exodus of common folks driven out by famines and the violence of the Cultural Revolution.

Between 1952 and 1965, at least 1.5 million sought refuge in Hong Kong from the party, accounting for nearly half of the population at the time.

For many, the dash for freedom is etched into family lore, along with the trauma of life under Communist rule.

But even during colonial times, the Communists were never far away from Hong Kong.

Communist supporters played a walk-on role in the mass strikes of 1922 and 1925 in the then-Crown colony. Agitators in the Communist-backed labour union instigated riots in 1967 in which 51 people died and 848 were injured.

Afterwards, colonial authorities resolved to weed out Communist groups by mandating government registration, thereby driving all of them underground – bar one.

Xinhua as party front

Xinhua News Agency, set up in the dying days of World War II as the party’s liaison office after Communist fighters played a critical role in defending rural parts of Japanese-occupied Hong Kong, was allowed to operate legally, according to the book “Underground Front, the Communist Party in Hong Kong” by Christine Loh, a former member of Hong Kong’s legislature.

Until the 1997 handover, Xinhua would act as the de facto Chinese mission and the party’s command centre in the city.

In 1987, however, three years after the Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed to return Hong Kong to Chinese rule, then-Xinhua director Xu Jiatun chose a party member who was working incognito as a school teacher to be his deputy. It came as a shock to Hong Kong society. Xu saw it as a much-needed reminder of political reality.

“Xu put it to me this way: ‘Now that Hong Kong is going to return to Chinese sovereignty, better let Hong Kong people get used to the fact that the CCP is in HK,’” said Ching Cheong, a longtime commentator on Chinese politics who at the time was a top editor at Wen Wei Po, one of the Hong Kong dailies controlled by the state media group.

Two years after the handover, the Liaison Office of the Central People’s Government officially replaced Xinhua. The Liaison Office was, Ching said, under Beijing’s strict orders to abide by the “one country, two systems” framework hammered out with the British and not to meddle in Hong Kong’s affairs.

However, in 2003, after half a million people took to the streets to oppose Beijing’s push for anti-sedition legislation – and prevailed – the liaison office found an excuse to get involved, albeit still by proxy.

Resources for electioneering for the territory’s two pro-Beijing political parties became more bountiful, funnelled through the liaison office as well as donated by local tycoons eager to curry favour with Beijing at a time when China’s economy was starting to take off.

About 10 years later, as China’s President Xi Jinping continues to consolidate his power, the party – which he leads as general secretary – is increasing its dominance over the mainland. In Hong Kong, the public for the most part treats the party’s creeping presence as an afterthought.

Over the past year, however, pronouncements by the liaison office have become more frequent, such as: “Patriots must govern Hong Kong. Anyone who opposes the party can’t be called as a patriot.”

At the symposium two weeks ago, it reminded delegates: “No Communist Party, no ‘one country, two systems’,” the framework meant to ensure the colonial status quo of civil liberties and rule of law for 50 years after the handover.

“The message that the party is supreme is clear,” Lui told Al Jazeera. “No more couching party leadership in terms both fuzzy such as ‘the central government’ and warm, like ‘the motherland’.”

At the handover, it was agreed Hong Kong’s chief executive would be chosen by a committee with the candidates first having to pass muster with Beijing. In the legislature, only half the seats would be directly elected, ensuring Beijing would be able to maintain control while providing Hong Kong people some political say.

But new electoral rules imposed by Beijing have drastically reduced the number of directly-elected seats and pro-democracy politicians have been disqualified under the National Security Law imposed last year. Most are in jail while others have fled into exile.

Speculation is growing that the party is eyeing new inroads into Hong Kong’s electoral politics.

Just when a mainland academic and party mouthpiece disparaged the territory’s pro-Beijing parties as “loyal losers” after the pro-democracy camp won the 2019 district council elections by a landslide, a new political group, the Bauhinia Party, emerged seemingly out of nowhere last December.

Founded by mainland Chinese immigrants, Bauhinia boasted a membership goal of 250,000, even though the main pro-Beijing party had managed to garner only 50,000 members in 30 years. The ambitious goal has fuelled suspicion that the party is a front for the Communists – seeking to plant members in the elected office while maintaining the façade of “one country, two systems”.

Ching, the commentator, estimates there could be at least 400,000 Communist Party members waiting in the wings in Hong Kong, although no one really knows who they are or whether they joined the party locally or on the mainland.

“Beijing has concluded that Hong Kong people running Hong Kong isn’t working,” Ching said. “So now the party wants to play a direct role.”