Indigenous chief to Trudeau: Turn over residential school records

Experts say the 200 likely graves at Kamloops Indian Residential School are only the beginning.

Warning: The story below contains details of residential schools that may be upsetting. Canada’s Indian Residential School Survivors and Families Crisis Line is available 24 hours a day at 1-866-925-4419.

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation Chief Rosanne Casimir on Thursday called on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the Mission Oblates of Mary Immaculate to open their student attendance records “immediately and fully” so her community can identify the hundreds of children buried on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsImams in Canada express solidarity with Indigenous people

More than 600 graves found at Canadian Indigenous boarding school

‘Horrific’: Another discovery of Indigenous graves in Canada

Casimir said her community’s search has only just begun, and she asked the provincial and federal governments to contribute funding and resources to help her community continue the investigation, and protect children’s remains.

“To the Prime Minister of Canada Justin Trudeau, we’re still waiting for you to reach out to us to acknowledge the latest truths from the Kamloops Indian Residential School. I look forward to a fulsome conversation where we can finalise the details of the federal government providing the needed support as well as access to our student records,” said Casimir at a news conference in Kamloops, British Columbia.

From the late 1800s until 1996, Canada forced 150,000 Indigenous children to attend assimilation institutions called “residential schools”, where they were forbidden from practising their culture or speaking their language. Many were physically and sexually abused, and thousands are believed to have died.

In May, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc was the first in the country to release a preliminary discovery of 215 Indigenous children buried in unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School that were found using ground-penetrating radar.

In recent months, other First Nations have used the same technology to search residential school sites, bringing the total number of Indigenous graves to more than 1,000 — many of which were not included in historical records, or had headstones removed.

Searching for graves

On Thursday, experts said only two acres (0.8 hectares) of the 160-acre (65-hectare) residential school site have been searched with ground-penetrating radar. Sarah Beaulieu, the radar specialist who participated in the search, said she further analysed the probable grave sites and concluded that there are approximately 200 likely graves — not 215 as first reported.

“With ground-penetrating radar, we can never say definitively that they are human remains until you excavate,” she said. “They have multiple signatures that present like burials, but because of that we need to say that they are probable until one excavates.”

Beaulieu said survivors led the search because they knew there were graves at the site, adding that archaeologists found a juvenile tooth near the site in the late 1990s or early 2000s, and a tourist found a child’s rib bone in the same area in the 2000s.

She said it was likely the graves contained children’s remains. “The majority of the anomalies were between 0.7 and 0.8 metres (27.5 and 31.5 inches) below the surface, which is fairly shallow, and it fits with the knowledge keepers’ descriptions of children having to dig graves, for one. It also fits with when you have a juvenile burial, because they are smaller in length, they typically are not dug as deeply.”

Beaulieu said no graves have been excavated yet. It is not clear when or if an excavation will happen.

“We are here today because of Indian Residential School survivors and intergenerational survivors who were unrelenting in carrying those painful truths about missing children forward,” Casimir said. She said survivors witnessed abuse and were required to dig graves, and it is because they spoke their truth that her community can verify where children are buried.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a years-long process documenting survivors’ stories, confirmed 4,100 children who died in the institutions – from abuse, neglect, disease, fire, and from exposure after running away.

But the full scope of how many children died, and the causes of their deaths, is still unknown. According to the TRC, it was not until 1935 that the government adopted a formal policy on how to report and investigate deaths at the institutions. The commission found that, for half of the recorded deaths, the government did not include the cause of death.

More than 7,000 survivors of the institutions testified before the TRC. In its final report (PDF), the commission concluded the practice was cultural genocide, and that Canada had “set out to destroy the political and social institutions” of Indigenous people with a goal of seizing land.

According to the UN, the policy of forced assimilation institutions was popular all over the world — in Canada, the United States, Latin America, Australia, New Zealand, Asia, Russia, Scandinavia and East Africa — because it was cheaper than waging war against Indigenous people.

Survivors’ stories

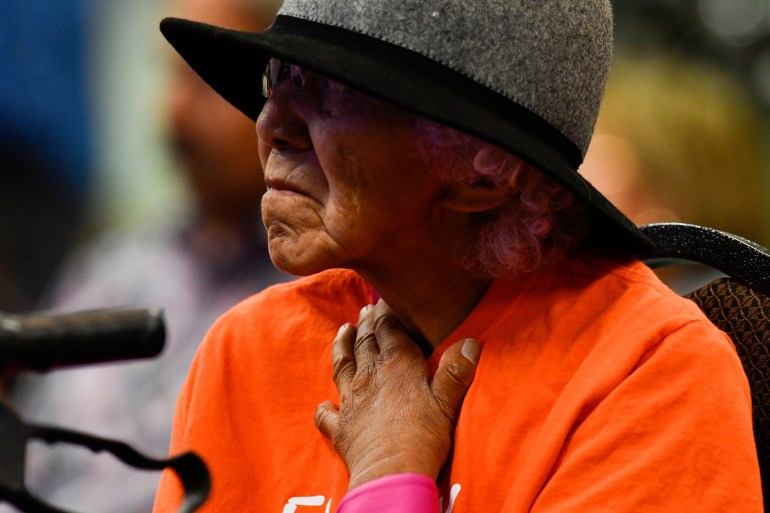

During the news conference, survivors of the Kamloops institution shared their stories.

Mona Jules said her 13-year-old sister became sick and passed away at the Kamloops institution, but her parents were not notified until after her death. “They wanted to know, why wasn’t she taken to a doctor, to the hospital? It was right across the bridge,” she said. “There were no answers.”

Jules said she and other children were beaten for speaking their Indigenous language. She is still fluent and has spent her life teaching it to anyone who wants to learn.

“I’ve spent years trying to revive what that school has snuffed out. And it’s working — we have many of our young people who speak it and they’re running language departments, having meetings in the language, speaking it to one another. I still work with them, when I can, and I’ll continue to do that for as long as I can.”