Haiti: Many questions, few answers one month after Moise killing

Haiti has asked the UN to launch an international investigation into President Jovenel Moise’s assassination on July 7.

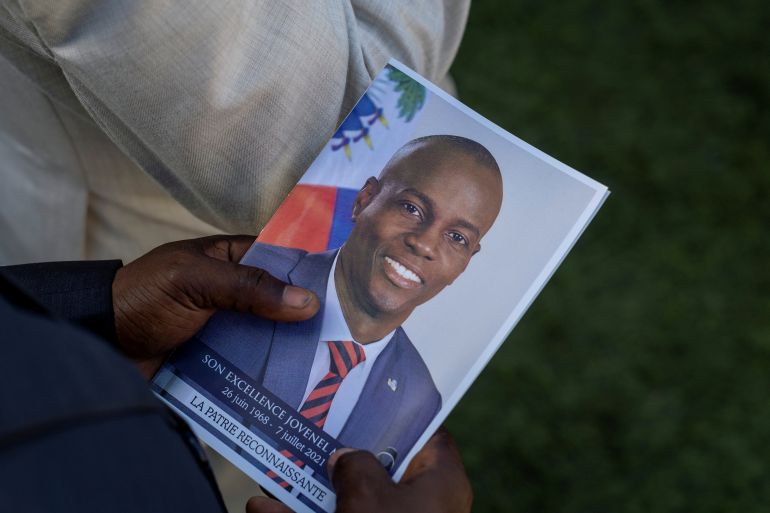

The assassination of Haitian President Jovenel Moise in the early hours of July 7 sent shockwaves across the world, fuelling fears of worsening political instability and gang violence in the Caribbean nation.

But one month after a crew of armed mercenaries stormed Moise’s home in the capital, Port-au-Prince, myriad questions remain unanswered about what took place – and about what path forward Haiti should chart.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIn Pictures: Haiti prepares to bury its slain president

Haiti arrests top security chief in Moise murder investigation

Haiti PM vows to work to hold elections ‘as quickly as possible’

“The country is still asking for answers,” Laurent Lamothe, who served as Haitian prime minister from 2012 to 2014, told Al Jazeera in an interview on Saturday.

“The country is still in shock. People are very upset. The information is slow to trickle in and everybody is asking the same question: Where are the masterminds, those who are responsible for financially paying for this horrendous operation?”

Haitian authorities say they have arrested 44 people in connection with the killing, including 12 Haitian police officers, 18 Colombians who were allegedly part of the mercenary team and two Americans of Haitian descent.

The head of Moise’s security detail is among those arrested in connection with the plot, but Jean Laguel Civil’s lawyer has said his client’s arrest was politically motivated.

On Thursday, the Haitian government requested help from the United Nations to conduct an international investigation, saying that Haiti considered the attack an international crime due to the alleged role of foreigners in planning, financing and carrying it out.

“I hope that the UN is going to respond favourably because that’s the least that the UN can do for Haiti and the Caribbean,” Lamothe said, “remembering that Haiti is the first Black republic in the world and we deserve all the international cooperation to find out who killed the president.”

Meanwhile, the Haitian justice system has struggled to find a judge willing to probe the killing.

“It is a sensitive, political dossier. Before agreeing to investigate it, a judge thinks about his own safety and that of his family,” one judge told the AFP news agency on condition of anonymity this week. “For this reason, investigating magistrates are not too enthusiastic about accepting it.”

Several magistrates have told the dean of the Court of First Instance in Port-au-Prince that they are not interested in working on the assassination.

Senior magistrate Bernard Saint-Vil said he would announce on Thursday the name of the investigating magistrate chosen to take on the case, but in the end, he could not because no judge wanted the job.

What next?

Questions also continue to swirl about what comes next for Haiti, where residents recently expressed fears that Moise’s killing “shows that no one is exempt” from the violence that surged during the president’s tenure.

The presidency of Moise, who took office in 2017, was marred by corruption allegations as well as mass protests after he refused to step down in February of this year despite opposition leaders, rights advocates and legal experts arguing that his term had expired.

The Haitian president had been governing by decree since January 2020 after parliamentary terms were left to expire, while several key government institutions were not functioning.

Moise also oversaw surging gang violence in Port-au-Prince that left countless dead, displaced thousands, and spurred accusations from rights groups that “the silence of the state authorities proves their total disinterest in the massive and systematic violations” of peoples’ rights.

Amid a lack of clarity and competing claims over who would take control after Moise’s killing, Haiti last month appointed a new interim prime minister, Ariel Henry. Henry has promised to hold elections “as quickly as possible” to get the country out of its political crisis.

But leading Haitian civil society leaders have questioned whether holding a vote later this year – a key demand from the UN and the United States, among other international actors – is possible amid the widespread insecurity.