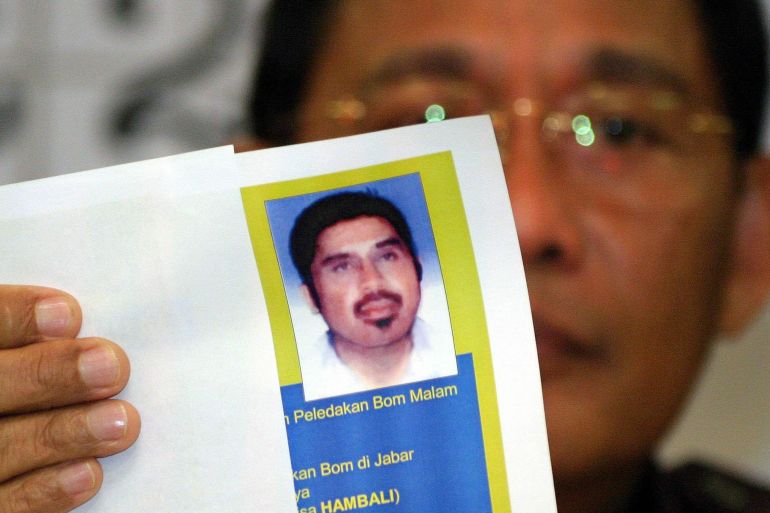

After 16 years in Guantanamo, will Hambali get a fair trial?

Indonesian faces a military commission over his alleged role in the Bali bombing and JW Marriott hotel attack 20 years ago.

Medan, Indonesia – Nasir Abbas, a former member of the Indonesian hardline group Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) describes fellow recruit Encep Nurjaman as “typically Javanese”.

Nurjaman, who is better known by his nom de guerre Hambali as well as by the alias Riduan Isamuddin, was “polite”, “soft” and “proper”, Abbas told Al Jazeera, remembering the time the two men were part of one of the most fearsome groups in Southeast Asia.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhy is Guantanamo Bay still open?

Judge says US held Afghan man unlawfully at Guantanamo Bay

Guantanamo Bay: ‘The legal equivalent of outer space’

Hambali and Abbas both trained in military combat together in Afghanistan in the 1990s, before joining JI which was labelled a terrorist organisation by the United States government after the group claimed a string of attacks across Indonesia in the early 2000s, including the Bali Bombing in 2002, which left more than 200 people dead.

“He was so eloquent and so clever. You couldn’t help but be left with a good impression of him,” said Abbas, who co-operated with the authorities following his arrest and now works on deradicalisation programmes for the Indonesian government.

The United States did not feel that way.

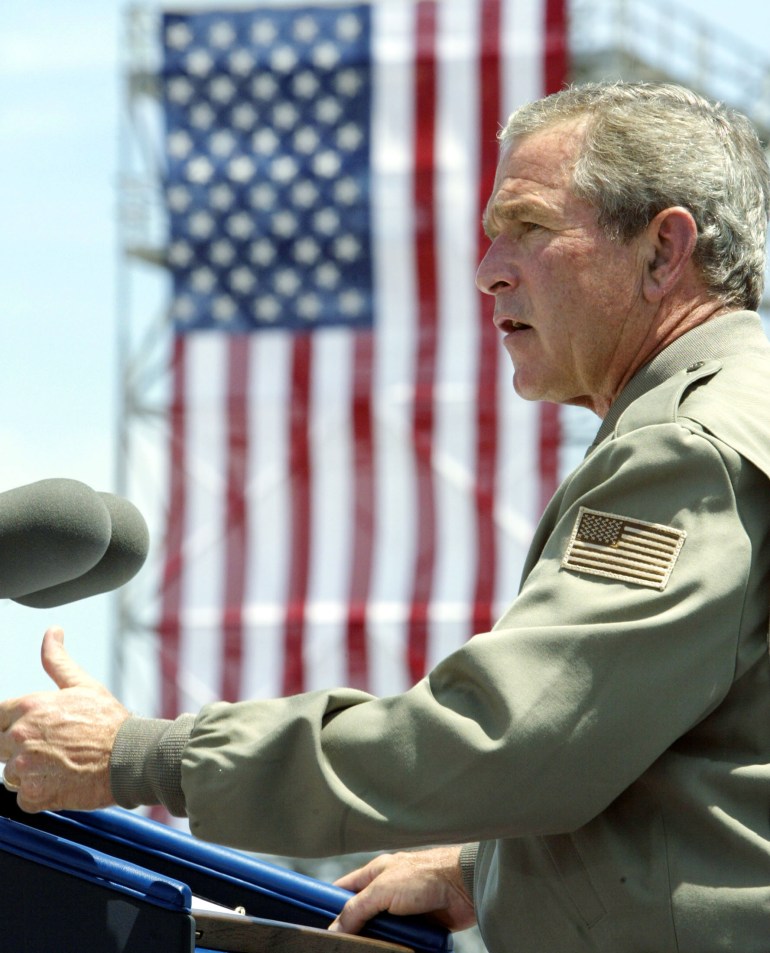

Hambali, who is now 57, has spent the last 16 years at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba, and was described by former US President George W Bush as “one of the world’s most lethal terrorists”.

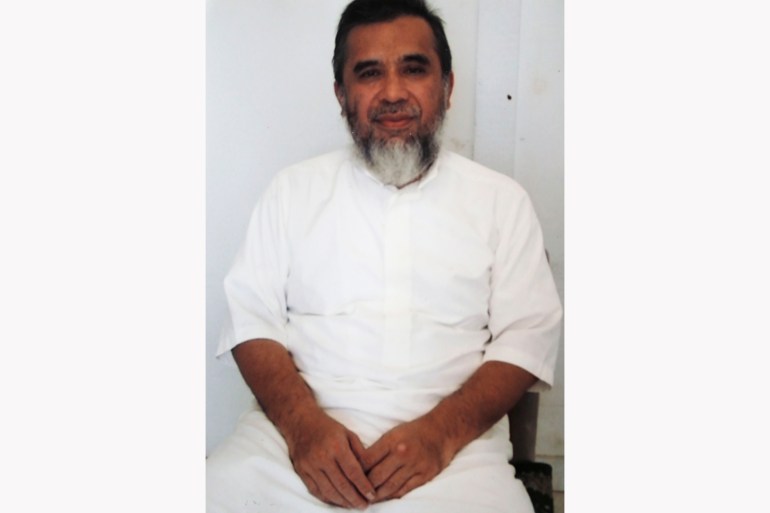

Twenty years since the first detainees were sent to Guantanamo, Hambali remains one of 39 men still held there.

Of 800 incarcerated in the facility since it was opened, only 12 have been charged with war crimes and have stood, or will stand, trial at the facility’s Camp Justice in front of a military commission. Hambali, who is charged with murder, terrorism and conspiracy, is one of them.

“The position of the United States Government is that the individuals who are in Guantanamo generally, but also when charged in the military commissions, are a category of what are called unlawful combatants,” said Michel Paradis, a human rights lawyer, national security law scholar and lecturer at Columbia Law School in New York.

“Hambali is a combatant in the war on terrorism in the government’s view and, as such, can be prosecuted for war crimes.”

In court documents seen by Al Jazeera, these war crimes relate to the 2002 Bali bombings, which targeted people enjoying a night out in the buzzing Kuta district of the island, and a 2003 attack on the JW Marriott Hotel in Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, in which 12 people were killed. Hundreds were injured in both Jakarta and Bali.

Hambali will stand trial with two Malaysians and alleged “accomplices” – Mohammed Nazir bin Lep and Mohammed Farik bin Amin – but some question whether they will be able to get a fair hearing.

“A recurring feature of the War on Terror has been the invocation of terrorism as an unprecedented and exceptional act. This is despite it being a recurring strategy used by a variety of groups, movements and governments throughout history,” Ian Wilson, a senior lecturer in politics and security studies at Australia’s Murdoch University, told Al Jazeera.

“This ‘exceptional’ nature has been used to rationalise measures that circumvent or negate existing legal and rights frameworks, including those inscribed in constitutions such as rights to due process and presumption of innocence. This ‘state of exception’ in response to the perceived risk and threat of terrorism has resulted in significant deterioration in the rule of law, and major swings towards illiberalism in democratic states.”

Wilson says Guantanamo Bay is an example of this approach – a place considered of “exceptional sovereignty” by Washington, but also somewhere portrayed as outside the formal legal jurisdiction of the United States.

Torture

Detainees such as Hambali, have not only been denied the legal rights and due process that would have been afforded them by the constitution in a trial on US soil, but also the rights in the Geneva Conventions given to those being tried for war crimes.

Hambali, through his lawyers, has alleged that he was brutally tortured following his arrest in Thailand in 2003, after which he says he was transferred to a secret detention camp run by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and tortured as part of the agency’s Rendition, Detention and Interrogation Program (RDI) which is sometimes referred to as the “torture programme”.

The policy was adopted in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks on the United States with then-President Bush agreeing that certain torture techniques could be justified if they were able to extract intelligence that would prevent other attacks against the country from happening. Under international law, torture is never justified.

According to Hambali’s lawyer, the Indonesian was stripped naked, deprived of food and sleep and made to stand in stress positions – such as kneeling on the floor with his hands above his head – for hours as part of the programme.

He was also allegedly subjected to “walling” – a torture technique where interrogators place a collar around a detainee’s neck and slam their head against a wall.

Other Guantanamo detainees have described being sexually assaulted and waterboarded while in detention.

The Senate Intelligence Committee investigated the CIA’s rendition programme amid persistent allegations of torture at Guantanamo and other so-called CIA black sites around the world.

Released in 2014, the report found that the torture techniques used – referred to euphemistically as “enhanced interrogation techniques” – were not only inhumane, but also ineffective in obtaining intelligence.

The majority of detainees, including Hambali, gave incorrect information to the authorities simply to make the torture stop, the report said.

“He had provided the false information in an attempt to reduce the pressure on himself…and to give an account that was consistent with what [Hambali] assessed the questioners wanted to hear,” the report said, citing a CIA cable.

‘Worst of both worlds’

During his time with Jemaah Islamiyah, which was affiliated with al-Qaeda, Hambali was most often described as a “money man”, according to Abbas.

His main role was collecting and distributing funds from the organisation’s many donors, among them al-Qaeda’s former leader, Osama Bin Laden, who is thought to have sent money for the Bali Bombing directly to Hambali.

However, in Abbas’ telling, Hambali agreed with Bin Laden that civilians could be targeted in terrorist attacks, something that was extremely controversial among other JI operatives, many of whom only considered military targets as fair game.

“We were trained in a military setting in Afghanistan with military knowledge and I was not comfortable with attacking civilian targets,” said Abbas.

“I wouldn’t allow it. No one involved in the Bali Bombing was brave enough to ask me for anything. They knew I would never agree to the killing of civilians. Those who did agree were misguided and I told them that.”

Three of the main perpetrators of the Bali Bombing were sentenced to death in Indonesia and executed, while a fourth perpetrator, Ali Imron, was given a life sentence after he apologised and expressed remorse.

Imron has always maintained that Hambali had no prior knowledge of the attack.

Twenty years since the bombings – the worst attack in Southeast Asia – Abbas says he feels that his former comrade should be returned to Indonesia to stand trial.

It is a view shared by Indonesian human rights lawyer Ranto Sibarani who says the Indonesian government should have tried to negotiate his repatriation.

“No matter how serious the accusations or charges against Hambali, he is still an Indonesian citizen who deserves protection according to the law,” Sibarani told Al Jazeera in August.

“That’s a big question that’s going to loom over the trial,” said Paradis. “Does the United States even have the authority to prosecute him? Terrorism is not a war crime.”

In 2009, the US departments of justice and defence described the military commissions as “fair, effective, and lawful”.

“Military commissions have been used by the United States to try those who have violated the law of war for more than two centuries,” it said in a press statement.

No date has been set for Hambali’s trial, but many are pessimistic about how the legal process will play out once the commission finally gets under way.

“The military trials are fatally flawed and the legal process has been thoroughly compromised by the CIA torture programme,” Quinton Temby, an assistant professor in public policy at Monash University, Indonesia, told Al Jazeera.

“It’s the worst of both worlds: the detainees won’t receive a fair trial and the families of victims won’t see the perpetrators held to account in open court.”