Should the EU impose a travel ban on all Russians?

Al Jazeera speaks to analyst Natia Seskuria about the bloc’s dilemma over restrictions on Russian nationals.

After the Ukraine war began, the European Union was quick to restrict Russian nationals from entering.

But whether the 27-member union should totally ban Russian tourists is up for debate.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsLatvia says it will not welcome Russians fleeing mobilisation

Finland to bar Russians after Putin’s mobilisation order

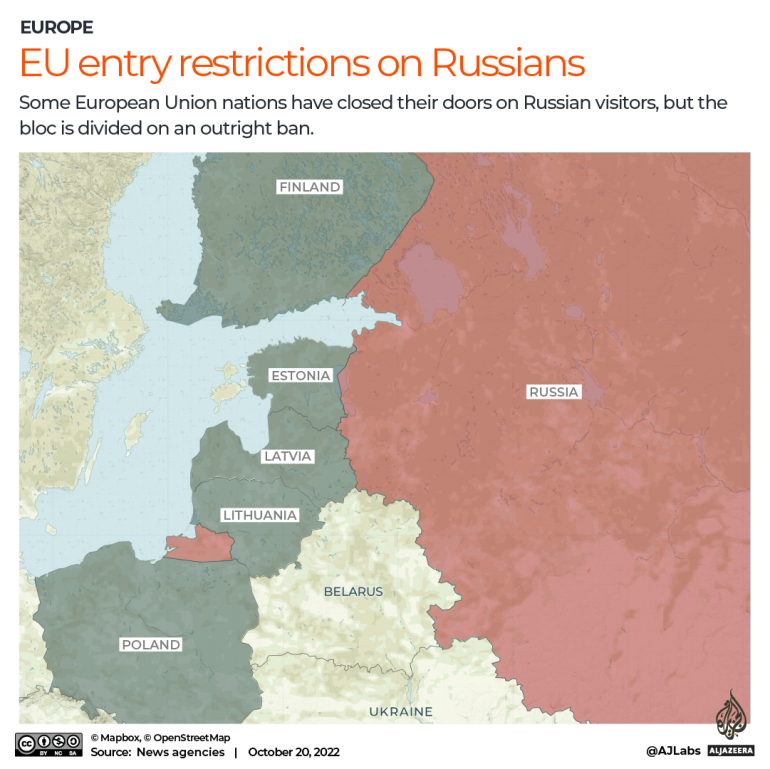

The bloc’s eastern members – including the Baltic states and Poland – are in favour of such a move, while EU powerhouses France and Germany have voiced opposition to the idea.

Al Jazeera spoke to Natia Seskuria, a Russia expert and associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI), a United Kingdom-based think-tank, about the moral and practical implications of restrictions.

Al Jazeera: You have called for the EU to impose a blanket ban on Russian tourists. Why?

Natia Seskuria: This is quite a radical decision, but the times we’re living in and what Ukrainians are experiencing right now are very extreme.

It’s very important that Russian citizens feel the burden and real consequences of this war.

I, of course, don’t think that a visa ban will force [Russian President Vladimir] Putin to stop the war – there are far greater leverages such as sanctions and they are being used right now in varying degrees by the West.

But this is one way to make ordinary citizens feel responsibility and make them acknowledge what their regime is doing against Ukrainians.

Al Jazeera: The alternative argument is that the EU’s borders should be open for Russians, particularly for those who face being forced into war …

Seskuria: The problem is that it is not necessarily the case that Russians who are fleeing the country are against the war.

There are people who support the war, but just don’t want to go and fight in it themselves and risk their lives.

If the EU’s borders stay open, they will receive a lot of people who are not only desperate to flee Russia’s extremely violent and authoritarian regime … but also a lot of Russians who have voted for Putin and who will be happy if he wins this war. This is obviously very problematic.

When it comes to humanitarian visas, the EU can work on that because there are journalists, civil society activists and others who have opposed the war from the beginning and want to escape but cannot because they don’t have the right to do so currently.

This is one gap that should be addressed properly [by the EU].

Al Jazeera: Russia is a vast country with a huge population. Who exactly do you think would be affected by an outright ban?

Seskuria: A lot of Russian citizens don’t even have a passport. Poverty in Russia is a huge problem and a lot of Russians have never travelled abroad.

So this outright tourist visa ban would target specific societal groups and those are the middle classes and upper classes.

[For many], the only option would be to travel towards Central Asia, which is relatively cheaper.

There is a certain segment that can be targeted by this ban … and it is those Russians who have been particularly hypocritical by spending a lot of time in Western European states while also still supporting the oppression and violence that Putin’s regime has exercised.

Al Jazeera: Powerful EU members France and Germany have warned against bans, saying the restrictions would feed into Moscow’s anti-Western narrative and risk estranging future generations of Russians. What’s the likelihood of a total travel ban?

Seskuria: I don’t think it’s going to happen, because this discussion has been ongoing since at least late summer. We have seen sentiments differ in different countries.

France and Germany especially have made it pretty clear that this will not be something they will support. So I think it’s going be up to individual member states to make decisions and introduce a [national-level] visa ban or not.

I’m not expecting the EU to announce a unified decision.

Al Jazeera: What might unfold in non-EU countries that border Russia, such as Georgia and Kazakhstan, which have welcomed floods of Russians fleeing the draft?

Seskuria: It’s an interesting situation because none of these countries has experienced such a huge flow of Russians before and a lot of their citizens are very frustrated by the influx.

There is a certain pressure on those governments to impose new visa regulations, because in Georgia, it is currently the case that anyone [with a Russian passport] can enter unless they have violated the law in occupied territories [held by Moscow] or bear pro-war symbols.

There isn’t any real limitation – they can stay for a year, and after that, if they cross the border for a day and come back, they are permitted to stay for another year. They can move almost indefinitely to the country.

Russia has used a pretext of protecting its citizens many times in the case of [taking military action in] Georgia and in Ukraine. A lot of people are worried that at some point, Putin might just claim that he has to “protect” his citizens in Georgia against the “Georgian oppressors” let’s say, and he can escalate tensions that are already there.

I’m not sure whether the [Georgian] government will impose any sort of restrictions because it also looks at that as maybe being perceived as some sort of provocative move, so they are taking a very much cautious stance.

Although I am not expecting any measures to be immediately enforced, there is certainly a lot of frustration within society. It is the same in Kazakhstan, where a lot of people are becoming worried about this huge influx of Russians.

And there are questions, for example, about what these Russians will be doing going forward, such as if and when they run out of money because obviously, it’s going to be hard for them, especially in Georgia, because Georgia is not a Russian-speaking country … to relocate, find jobs and settle down.

Al Jazeera: After the mobilisation order, some EU states closed the door on Russian tourists. How do you think the situation could evolve from here?

Seskuria: It’s definitely much more difficult now [for Russians] to find the loopholes and enter the EU [and the Schengen Area zone] because Finland, Poland and the Baltic states – the ones that have the land borders with Russia – have now adopted quite a tough position.

Some can, for example, travel to Turkey and then relocate to different countries using air connections, but that obviously incurs financial costs and a lot of people, I assume, would not be able to afford that.

So although there are still ways [for Russians to enter the EU] … with all of the restrictions, Russians understand they have less chance to find shelter in the bloc.

Overall, I think we will still see some numbers still arriving, but these will decrease. But at the same time, I don’t expect some unified policy to be adopted. I think it’s going to continue to be as fragmented as it is right now and it’s going to be up to individual countries to make further decisions.

This interview was lightly edited for brevity and clarity.