Daughters of murdered Indigenous woman push Canada for action

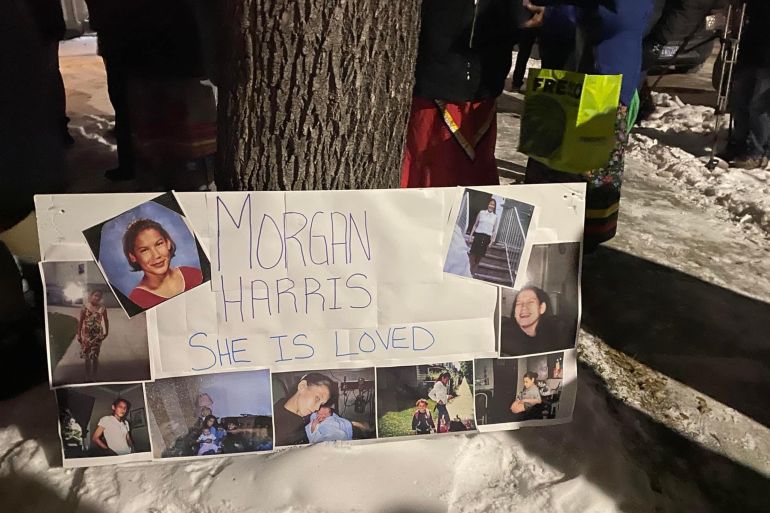

Morgan Harris is among the victims of an alleged serial killer accused of murdering Indigenous women in Winnipeg.

Two daughters of an Indigenous woman murdered in a recently announced killing spree are calling on officials in Canada to search for her remains in a local landfill after police said they can no longer continue.

Morgan Harris, 39, is one of four women believed to have been targeted by an alleged serial killer in Winnipeg, the capital city of the prairie province of Manitoba.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsIndigenous child compensation deal falls short: Canadian tribunal

Indigenous people seek leadership, respect in biodiversity battle

On December 1, Winnipeg Police Chief Danny Smyth charged Jeremy Skibicki, 35, with three counts of first-degree murder, including the death of Harris. Skibicki’s lawyer, Leonard Tailleur, said his client intends to plead not guilty on all counts.

Skibicki was previously arrested on another count of first-degree murder in May, after the partial remains of 24-year-old Rebecca Contois, a member of O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi (Crane River) First Nation, were discovered in a garbage bin.

More of Contois’s remains were uncovered at Winnipeg’s Brady Landfill. Police believe the remains of two more women, including Harris, might be buried at the Prairie Green Landfill.

But at a press conference on Tuesday, the police force’s head of forensics said it would no longer be feasible to search the landfill, because of how much time had passed and the amount of garbage that has been dumped. The site is routinely compacted via heavy machinery.

Harris’s daughters Cambria, 21, and Kera, 18, are among those denouncing the decision. They travelled from Winnipeg to the capital city of Ottawa this week to meet with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and demand that the police continue the search for their mother’s body.

“It’s dehumanising. They’re treating us like animals,” Cambria told Al Jazeera, as she grieved the loss of her mother. Manitoba Premier Heather Stefanson joined Winnipeg Mayor Scott Gillingham on Thursday to announce that the landfill has paused its operations while the city considers next steps.

Both Harris and another of Skibicki’s alleged victims, 26-year-old Mercedes Myran, are from the Long Plains First Nation. Their names, along with a fourth, unidentified victim, were announced at a December 1 press conference, when police revealed they believed Skibicki to be a serial killer.

Indigenous elders have given the fourth victim a ceremonial name – Mashkode Bizhiki’ikwe, or “Buffalo Woman” – to honour her life and spirit. All four murders are thought to have taken place between March and May of 2022.

Cambria and Kera remember their mother as a “strong and resilient woman”. Though she was only five feet (1.5m) tall, Harris had the courage to speak up for herself, her daughters told Al Jazeera.

“She had confidence, and people freaking loved her for it. She was not afraid to say what she wanted to say, and you can see it through us, like we’re literal embodiments of our mother,” said Cambria.

Harris was raised in foster care, an institution where Indigenous children are dramatically overrepresented. A 2021 Canadian census report found that 53.8 percent of children in foster care are Indigenous, though Indigenous youth accounted for less than 8 percent of the population aged 14 and under.

Harris ultimately became a mother to five children, the youngest of whom is just four years old. But as she succumbed to an addiction to prescription drugs, her children were taken out of her care. She started living on the streets of Winnipeg.

“She tried. She was in and out of treatment centres. She absolutely tried to survive,” Cambria said, explaining the “heartbreak” of watching her mother “get lost in the system and fall through the cracks of mental illness, addiction and homelessness”.

Cambria and Kera themselves were raised in foster care for most of their childhoods. They said that during their teenage years, they lived in group homes and children’s shelters in Winnipeg. Their younger siblings are still in foster care.

“But that doesn’t mean she wasn’t a great mother,” Cambria said of Harris. “She made the time to come out and see me, and I think that’s absolutely beautiful.”

Harris went missing in May. The family searched for her in the months that followed but turned up no leads. Cambria said she provided police with a blood sample in September which was then used to identify evidence linked to her mother.

The family was only told their mother was among the dead women when Skibicki was charged last week. Cambria believes that had the police acted sooner, they could have utilised the time to search the landfill. Still, she said, it’s not too late for them to continue the search.

“It might be like finding a needle in a haystack, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. We need to stop dumping garbage on top of them like they’re trash because they’re not. These women need a final resting place,” Cambria said. “And for them to just give up? I can barely get up. I can’t sleep, I can’t eat. I’m sick to my stomach.”

Her sister Kera has vowed to search the landfill herself if it comes down to it.

“I don’t care how long it takes,” Kera said. “These are women. These are people who need to be found. No human deserves to be left alone.”

Cindy Woodhouse, regional chief for the Assembly of First Nations, recently participated in a traditional blanketing ceremony for Harris’s daughters during a national chiefs’ gathering in Ottawa. She is among the advocates calling for Canada to declare a national state of emergency following the revelations about the killing spree.

“It’s an urgent national emergency, and we need systemic action to address the ongoing genocide against our women that leads directly to the loss of human life,” Woodhouse said.

To Woodhouse, the Winnipeg police chief’s decision not to search the landfill signals more violence towards Indigenous women.

“The message that the chief of police sends out to the greater community is that Indigenous women don’t matter. It’s like, ‘Oh, go throw them in the garbage and nobody will look for them,’” Woodhouse said. “Is that the message Winnipeg wants to send to this country?”

A national inquiry into Canada’s Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) has called the violence a genocide.

The inquiry’s report, released in 2019, concluded that “persistent and deliberate human and Indigenous rights violations and abuses are the root cause behind Canada’s staggering rates of violence” against Indigenous women, girls and two-spirit (2S) people, a term used by some in the Indigenous LGBTQ community.

“It’s beyond devastating,” said Nahanni Fontaine, an advocate and member of the legislative assembly for the New Democratic Party of Manitoba.

“It’s beyond enraging that we’re still sitting here talking about this. All I know is that our women, again – not only here in Manitoba or Winnipeg, but from coast to coast to coast – are in danger.”

The two-volume report calls for legal and social changes to resolve the crisis facing Indigenous women and girls. But Fontaine said that governments on all levels of Canada have failed to act.

“We have the blueprint of what has to be done. We have the 231 Calls to Justice,” Fontaine said, referencing the guidelines. “It’s all laid out.”

However, Fontaine believes a lack of political will is what ultimately allows the violence to continue.

“It isn’t a sexy political issue. If you’re looking at political parties and those that want to maintain power, there’s nothing sexy about it,” she said. “People know that it’s a lot of hard, gut-wrenching, uncomfortable work that also, incidentally, requires money. You just need the right people in positions of power to get it done.”

During a press conference on Tuesday, Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations Marc Miller said that federal, provincial and municipal governments have failed Indigenous women and girls, and continue to fail them.

“No one can stand in front of you with confidence to say that this won’t happen again, and I think that’s kind of shameful,” he said.

In an interview with Al Jazeera, Cambria said she feels like “a walking target” as an Indigenous person. But she and her sister Kera emphasised that their quest for justice won’t end in Ottawa.

“The fire has been lit, and no one is going to put it out,” said Cambria. “We’re going to war. Trust me: We’re not backing down.”