Can Russia return to the world stage, as other aggressor nations?

Analysts say while Putin may be viewed as reprehensible now amid Ukraine’s war, casting him aside looks unlikely because of Russia’s strategic power.

The war in Ukraine has turned Russian President Vladimir Putin into a pariah – at least in the West.

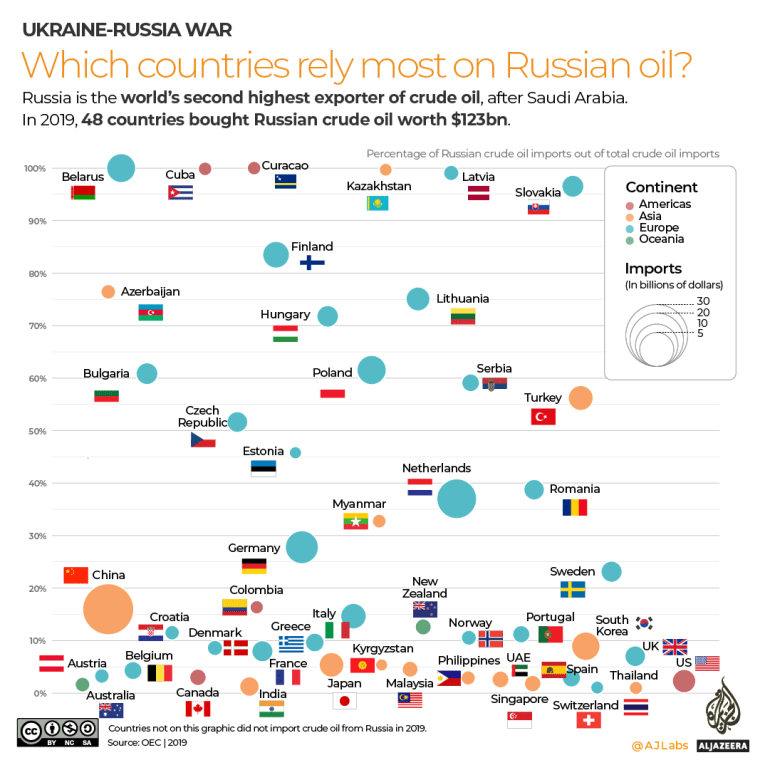

The United States is trying to remove Moscow from the Group of 20 (G20) block of nations and continues to penalise Russia with sanctions along with its European partners, which are simultaneously rushing to wean themselves from Russian oil.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsWill Ukraine be the next Chechnya?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine: List of key events, day 34

There are also loud and growing calls to try Putin at international courts for war crimes.

But at the same time, Russia remains a member of the United Nations Security Council, making it a veto power and pivotal to future voting issues, while powerful countries on the global stage, such as China and India, have not moved from Putin’s side.

Given the atrocities Putin is accused of committing, it seems almost inconceivable that he could ever again find himself in good standing in the West.

However, history teaches that more often than not, leaders who start wars are not always cast aside.

“There have certainly been leaders who have launched illegal aggressive wars with high civilian casualties but have nevertheless been accepted in some circles internationally, such as [US] President George W Bush and Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon,” Stephen Zunes, professor of politics and international studies at the University of San Francisco, told Al Jazeera.

“However, with no major country supporting Russia’s aggression, it is hard to imagine that Putin will not continue to be isolated in the international community.”

Explaining why Russia was at particular risk of longer-term isolation, he said: “The level of physical devastation and casualties thus far over a relatively short period is perhaps the worse in recent decades which, combined with the irredentist aims of the conquest, makes Russia’s war on Ukraine particularly reprehensible in the eyes of the international community.

“In addition, since Ukraine is a developed country with advanced communication capabilities, images of the destruction are being broadcast internationally to an unprecedented degree.”

But above all, the main reason Russia has drawn such sharp condemnation is because Ukrainians are predominantly white Christians living in an advanced democratic society, said Zunes, adding that Western empathy is higher now than it has been for Palestinians and Iraqis, and other recent victims of conflict.

Ukraine may prove to be the final straw for global powers, but there were hints before the invasion that Putin was “gradually withdrawing” from international cooperation, according to Erdi Ozturk, associate professor in politics and international relations at London Metropolitan University.

“[He is now] resorting to a new distinction between civilisations by synthesising nationalism with nostalgic visions of history, memory, and religion.

“It has been undoubtedly creating a jarring effect with Western powers, and it seems that it is very difficult for Putin to become a ‘respectful’ leader in the eyes of an international public.”

However, others believe that future cooperation with Russia is possible, if not necessary.

Graeme Gill, professor emeritus at the University of Sydney and president of the International Council for Central and East European Studies, told Al Jazeera: “At some stage, the West is going to have to shift from punishing Russia to working with Russia. Unfortunately, when this happens will be determined as much by domestic considerations.

“In addition, there will be differences within the West about when such moves should take place and what they should be, with the EU probably split on this.”

Gill argued that the war in Ukraine was no different than the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, the 2011 NATO bombing of Libya, the alliance’s bombing of Serbia in 1999, or the Saudi-led coalition’s current war in Yemen.

“There is a clear double standard operating and that cannot be hidden by all the rhetoric about international law and Russian crimes,” he said. “Terrible things are being done in Ukraine, and similar things have been done elsewhere, yet the international treatment is different. Perhaps this is a reason why the loud condemnation of Russia in the West is not generally echoed throughout much of the rest of the world, which has been content to condemn Russia in the UN, but has not made a major PR effort about it.”

Looking ahead, as criticism grows, reportedly even in the Kremlin, there is rising speculation over Putin’s future.

But while Russian dissidents continue to stress that the president and Russia are not synonymous and hope for a post-Putin future, “Putin will do everything to stay in power, and getting him out of office – either with the military, intelligence services or oligarchs – will not be that easy” said Erdi.

He added that Russia is an “enormous power” and has different levels of partnerships with both China and Europe.

“It will [be] difficult to completely cut off Russia from the international stage, especially for just one man, namely Putin.”