What’s behind pro-Russian attitudes in eastern Ukraine?

Observers say a ‘special kind of paternalism’ runs through the Russian-speaking regions full of coal mines, steel factories and chemical plants.

Kyiv, Ukraine – Seven weeks after Kreminna’s pro-Kremlin mayor was found dead with gunshot wounds, Russian forces seized the Ukrainian town on Tuesday as part of a renewed eastern offensive.

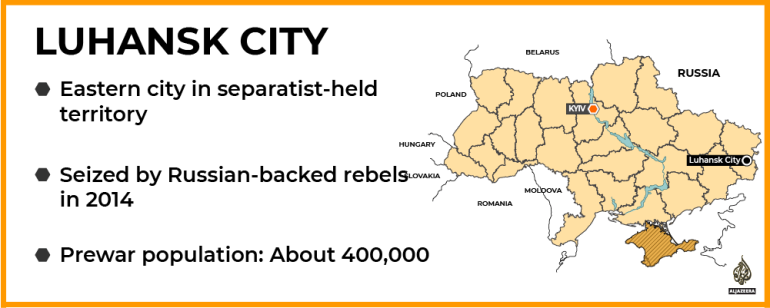

Volodymyr Struk, a truck driver-turned brewery owner, was a lawmaker with the Party of Regions, Ukraine’s largest pro-Russian force, from 2012 until 2014, in the southeastern region of Luhansk.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia likely to attack Kyiv again if Donbas falls: Zelenskyy

‘Battle for Donbas begins’ with explosions along all front lines

What does the ‘Battle for Donbas’ mean for the Ukraine war?

After separatists turned part of the area into a Moscow-backed “People’s Republic”, Struk moved there from Kreminna, a Ukraine-controlled town of 18,000 two hours northwest of Luhansk.

Ukrainian prosecutors charged Struk with separatism, but he returned to Kreminna – and was elected its mayor last November with nearly 52 percent of the vote.

While facing two arrest warrants, the balding 57-year-old proudly wore a banned pro-Moscow symbol – a black-and-orange ribbon.

Days before his death, Struk had said the Russian invaders were welcome in Kreminna. Then unknown men in camouflage abducted him from his house and, on March 1, his body was found.

“The entire state apparatus of Ukraine – the SBU [intelligence service], the Interior Ministry, prosecutors, courts – could not do anything with the openly separatist Struk for eight years because he had a lot of money. Most likely support from the Russian Federation,” Anton Herashchenko, an aide to the interior minister, wrote on Telegram on March 2.

He was “executed by unknown patriots as a traitor”, Herashchenko said of the killing – and attached a photo of Struk’s remains to his post.

Who are the pro-Russian Ukrainians in the east?

Between 2014, when the pro-Russian separatist uprising began and February 24, 2022, when Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, more than 13,000 people were killed in the conflict between the two nations.

Millions were displaced, and the rebel-held “people’s republics” of Donetsk and Luhansk, became totalitarian quasi-states, where hundreds have been jailed and tortured for pro-Ukrainian sympathies.

A stone’s throw away from the rebels, there are Ukrainian adherents of the “Russian world”, the Kremlin’s theory that denies the very existence of Ukraine – and prescribes its “liberation” through subjugation to Moscow.

According to observers, there is a predominant mentality in the rustbelt, the Russian-speaking regions of coal mines, steel factories and chemical plants, a “special kind of paternalism that emerged from the region’s industrial core,” Kyiv-based analyst Aleksey Kushch told Al Jazeera.

Its residents were used to Soviet-era benefits such as free healthcare and education, and now feel abandoned by the cash-strapped central government.

He said “centrist” Ukrainian parties are not able to address the population’s needs and “oligarchic” forces such as the Party of Regions and its political scions filled the niche.

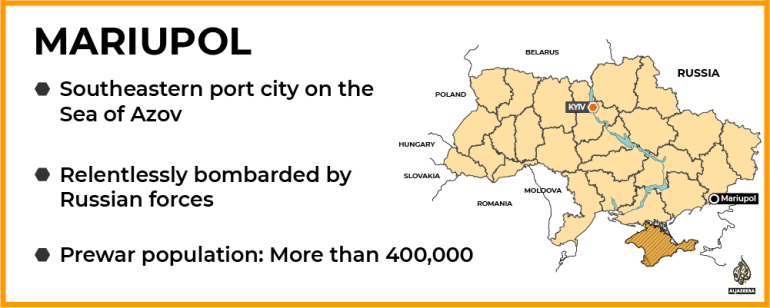

“Our electorate is pro-Russian,” Sergey Vaganov, a 63-year-old retired photographer from Mariupol, told Al Jazeera. “No major Ukrainian party even tried to work here, honestly. No one was fighting for the voters.”

Mariupol, the southernmost city of the Donetsk region, was briefly occupied by separatists in 2014 and became the region’s de-facto administrative capital when Ukraine regained control, but failed to win hearts and minds.

Given widespread apathy, turnout is generally low throughout Ukraine, and elderly, Soviet-born Ukrainians are among the most diligent voters; their ballots propelled Struk to the mayor’s seat.

Nostalgic about their Communist-era youth, they consume Russian television broadcasts and the Russian border is just hours away from almost anywhere in Donbas – where many have relatives and friends on the other side.

Ihor Saldyha, a 38-year-old resident of Kharkiv, which lies 40km (25 miles) from the Russian border, said some of the elderly people he meets on the streets of the besieged city remain pro-Russian.

Only Russian bombardment changes their mind, he says.

“When someone gets an incoming [shell] in his house, in his back yard – they all of a sudden begin to understand things,” he told Al Jazeera.

A community activist from Donetsk agrees.

“Putin did really enlighten some with his bombings. The least hopeless ones,” Nadia Gordiuk from the southeastern town of New York, which is near the separatist areas, told Al Jazeera.

Meanwhile, in some of Ukraine’s eastern towns and villages, years of “brainwashing” made many youngsters vehemently anti-Ukrainian, a displaced woman from Donetsk said.

“An entire generation that hates Ukraine with every cell of their body grew up there in the past eight years,” Oksana Afenkina, who fled for Kyiv in 2020 after receiving death threats, told Al Jazeera.

Sometimes, the actions of Ukrainian servicemen catalyse pro-Russian sympathies.

In 2014, during the conflict’s hottest phase, Ukrainian forces entered the village of Georgievka outside Luhansk – and found that Andrey Lubyanoi was the only man of fighting age there.

Others had fled to Russia or joined the separatists, but the 44-year-old construction worker had nowhere to go and stayed in the village to look after his three young daughters.

The Ukrainian servicemen tortured him and shot a bullet through his legs after he refused to confess, he told this reporter in 2016, having mistaken him for a rebel spy.

“No big deal, my legs healed,” he said with a look of desperate optimism.

The servicemen also threw a grenade in his basement, turning sacks of potatoes, slabs of smoked meat and dozens of jars of pickles into a pungent mess – and dooming his family to a winter of malnutrition, he claimed.

He said he detested the idea of living under Kyiv but could not take his family to Russia, because one of his daughters had no identification documents.

The latest Russian invasion has made life for pro-Russians on Ukrainian soil more complex.

Apart from Kreminna, four more town mayors in Ukrainian-controlled parts of Luhansk became turncoats, regional governor Serhiy Haidai said on April 3.

“After our victory, we will see how the laws on collaborating with the enemy will work on these people,” he said in televised remarks.

But for now, during the renewed eastern Russian offensive that has been dubbed The Battle of Donbas, they can leak information on the whereabouts of Ukrainian servicemen, military and fuel storage, as well as urge others to collaborate.

They also parrot the Kremlin’s accusations against the pro-Western government of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, of an attempted “genocide” of Russian-speaking Ukrainians.

“I was shocked by the genocide towards us on the part of the Ukrainian Nazism,” Serhiy Khortiv, a mayor of the town of Rubizhne said in a YouTube-posted video in early April.

“You are fascists, Europe and America spawned you, and you dance and sing for their money on our blood,” he said, addressing the government.

Later, the General Prosecutor’s Office said Khortiv faced up to 10 years in jail for “entering into a criminal conspiracy” with separatists and Russia.