Polls close in Hungary as Orban seeks a fourth term

Opposition parties unite to challenge Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who is hoping to extend his 12-year term.

Polls have closed in Hungary’s national election that will determine whether incumbent Prime Minister Viktor Orban will extend his 12 years in power by winning another term.

The contest has been the closest in years as the six main opposition parties came together and picked up a single candidate, Peter Marki-Zay, with the common goal of bringing down Orban and his Fidesz party.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsThousands in Hungary rally to support gov’t before elections

Russia’s war in Ukraine dominates Hungary’s election campaign

A 49-year-old marketing expert and the mayor of the city of Hodmezovasarhely in southeast Hungary, Marki-Zay was a surprise choice to emerge out of the opposition primaries. A conservative independent politician, he is a practising Catholic and the father of seven children.

He fought his campaign predominantly on the streets as billboards, most of the media, state television and radio are all under the control of the right-wing prime minister, who is accused of dividing the country, moving towards autocracy and getting too close to Russia.

“Instead of protecting the nation [Orban] has always been attacking the opposition for 12 years,” Marki-Zay told Al Jazeera. “He has been waging a war on everybody; homosexuals, the LGBTQ community, Roma, migrants, the left, Brussels.”

“He has been serving [Russian President Vladimir] Putin’s interests,” he added.

A proponent of what he calls “illiberal democracy”, Orban has taken many of Hungary’s democratic institutions under his control, and depicted himself as a defender of European Christendom against Muslim migrants and what he calls progressivism and the “LGBTQ lobby”.

In his frequent battles with the European Union, of which Hungary is a member, he has portrayed the 27-member bloc as an oppressive regime reminiscent of the Soviet occupiers that dominated Hungary for more than 40 years in the 20th century, and has bucked attempts to draw some of his policies into line with EU rules.

While the opposition called for Hungary to support its embattled neighbour and act in lockstep with its EU and NATO partners, Orban, a longtime supporter of Russian President Vladimir Putin, is portraying himself as an apostle of peace, who can keep Hungary out of the war and Hungarians safe.

“This is not our war we cannot gain anything, but we can lose everything,” he told a cheering crowd during a rally. “We have to stay out of it,” Orban said.

After the initial shock about the war next door, the peace rhetoric seems to be working for the voters. For a short time, polls had Fidesz and the opposition alliance neck and neck, but ahead of the vote the governing party pulled ahead.

It is likely that the huge power of Orban’s political machine will decide the result.

‘Decisive moment’

Electoral fraud is not out of the question, through fake proofs of residency, vote-buying, and manipulating the votes of ethnic Hungarians from abroad.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) has sent a full team of 200 people to monitor the election, a highly unusual move in an EU member country.

An interim report of the OSCE already indicated serious deficiencies. The report raised concerns that “the official functions of the government [are] being mixed with campaign activities or being misused as a campaign tool”.

There was a threat of “tactical migration of voters to closely contested constituencies”, according to the OSCE.

The OSCE had already categorised the two previous elections in Hungary in 2014 and 2018 as “free, but not fair”.

“Even if we win, this election is not free,” Marki-Zay, the opposition candidate, said.

OSCE election observers are touring the constituencies and monitoring the process, but had not reported any major irregularities by early afternoon.

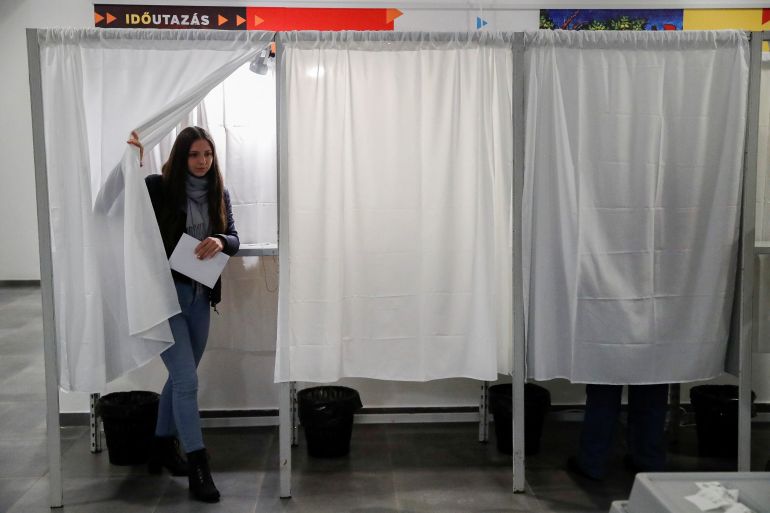

Voters waited patiently in line on Sunday in some of the constituencies in Budapest to cast their ballots.

Middle-aged Maria, emerging onto a busy crossroads in the capital’s 14th district after casting her vote, told Al Jazeera the election is “a decisive moment”.

Gergely, 30, said 12 years were quite enough of Fidesz, but admitted he is not very optimistic about an opposition victory.

Ferenc Horvath, a 51-year-old bank worker, says he is sticking with Fidesz. He’s largely uninterested, he claims, in the party’s culture war, but is very happy with economic policies that offer his family generous benefits and tax breaks.

Orban and Marki-Zay voted in the morning hours. The prime minister repeated his message that Hungary has to stay out of the war in Ukraine and warned that the opposition would drag Hungary into the conflict.

Marki-Zay urged voters to take the election as a chance for a real change.

Tim Gosling contributed reporting from Budapest, Hungary.