Joe Biden struggles to take action on US police reform

With Congress stalemated, the White House is stuck between reform advocates and police unions who are far apart on policies.

After more than a year in office, President Joe Biden has not yet delivered on long-promised police reforms in the United States, leaving Black civil rights advocates and community activists disappointed.

Biden’s campaign trail promise to deliver reforms came amid widespread protests in the summer of 2020 in the wake of the killings of Black Americans George Floyd and Breonna Taylor at the hands of mainly white police officers.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS: Former officer cleared in shooting during Breonna Taylor raid

Police will not be charged in ‘no-knock’ killing of Amir Locke

US police release name of officer who fatally shot Patrick Lyoya

“Watch what I do. Judge me based on what I do, what I say and to whom I say it,” Biden told a National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) town hall meeting in June 2020 as he sought the White House.

A month earlier, Floyd had been killed by a Minneapolis police officer kneeling on his neck while three other officers looked on, sparking worldwide demonstrations against police abuses. Biden, who was courting the Black vote, voiced support for the protesters and was elected president in November.

Since then, Black Lives Matter activists and other US civil rights groups have been asking the president to take several steps including holding officers who kill people accountable in court, establishing a national database of police killings and reimagining approaches to public safety.

The second anniversary of Floyd’s murder is May 25, an anniversary that might spur action.

Reform advocates further want to see an end to the militarisation of police through the transfer of government weapons and equipment, removal of police from schools and parks, and a reinvestment in communities of colour.

The White House had hoped that Congress would pass legislation that Biden could sign into law. An expansive bill bearing Floyd’s name addressed many of the reforms advocates were calling for.

Introduced in February 2021, soon after Biden took office and backed by Democrats, it passed a House vote on party lines, but has been blocked by Republicans in the Senate.

Late last year, White House policy director Susan Rice held a series of conference calls with civil rights and law enforcement organisations seeking input and sharing the administration’s thinking on issues.

In January, the White House signalled Biden would soon sign an executive order to push through police reforms, though changes he could make are limited without congressional backing.

The executive order has been shelved since then after police and Republican politicians objected strongly.

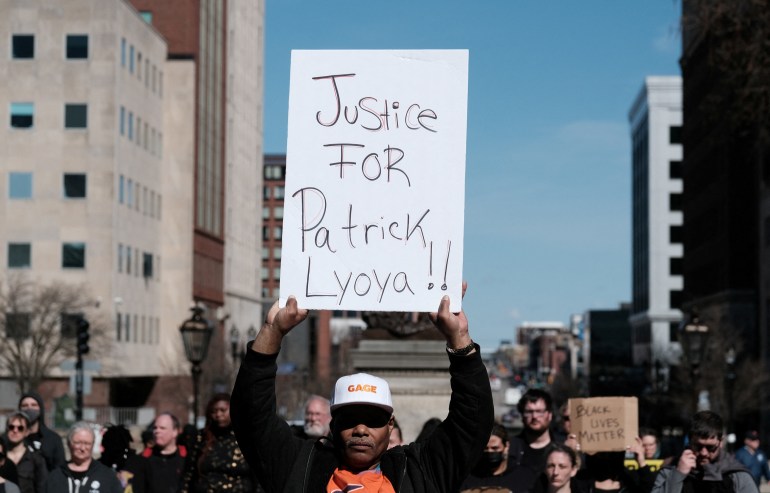

Recent killings by police of Patrick Lyoya in Michigan and Amir Locke in Minnesota, both Black men, have brought the issue back to the fore.

“The killing of Mr Lyoya underscores the continuing and urgent need to fundamentally rethink the approach to public safety in our country,” the NAACP said in a statement. Lyoya was shot in the back of the head by an officer after a traffic stop led to a foot chase and struggle.

Biden’s “intention is absolutely to sign a policing executive order”, then White House press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters on April 13, but offered no timeline.

Biden’s draft order, leaked in January and widely circulated, would have set national accreditation standards for police departments and opened a national database of “bad cops” – officers who had been tagged for misconduct, police and civil rights groups said.

Reform advocates applauded the move towards standard setting and data collection, but have continued to call for more far-reaching reforms like ending qualified immunity – which protects police officers from being sued -, increasing criminal prosecutions of police who abuse citizens’ rights and ending dangerous “no-knock” raids

“Although really good on a symbolic level and really good on certain very specific levels, it doesn’t achieve the kind of change that communities need,” Arthur Ago, director at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law said of the prospective executive order.

“The president’s power is very limited. He cannot implement some of the changes that people really want to see,” said Scott Roberts, senior director at Color of Change, an advocacy network.

Presidential limitations

Without Congress, Biden can not limit qualified immunity that in many instances shields police officers from civil lawsuits brought by victims of police misconduct.

Police groups have warned changing qualified immunity would have a chilling effect on aggressive policing.

Reform advocates also want a change in US law to allow more federal prosecutions of officers who kill or abuse people while violating their civil rights, like the four officers involved in Floyd’s death.

Biden can only encourage the Justice Department to explore civil rights prosecutions against police “more thoroughly”, Ago said.

Biden’s hands are also tied in ending so-called “no-knock” raids by state and local police like the one that killed Amir Locke in Minneapolis on February 2.

Locke, 22 years old, was asleep on a couch when armed police opened the door without knocking and then shot him in an early morning raid when they saw a gun in his hand. Locke, who was roused from sleep, had a permit to carry the weapon. Minnesota prosecutors decided not to charge the officer who fired at Locke.

“It did create a bad scenario. But under the existing law, probably nearly impossible to get a conviction,” said David Schultz, a professor of politics at Hamline University in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

Biden pivots

In his State of the Union address to Congress in March, Biden rejected calls to defund the police – a rallying cry of the 2020 protests – and instead called on lawmakers to provide more funding for police. That left reform advocates disappointed.

“I don’t think that the majority of the Democratic Party ever had their hearts in police reform,” said Melina Abdullah, a Black Lives Matter organiser in Los Angeles who participated in calls with Rice and civil rights groups in October.

“They were pressured into speaking in those terms by hundreds of thousands and even millions of folks being in the streets. But many of them are really beholden to these old models and to police associations themselves,” Abdullah told Al Jazeera.

Abdullah and others said they still are hopeful Biden will sign an executive order implementing reforms before May 25, the second anniversary of Floyd’s death, but expectations for what it will do are low.