Divisions over EU policy persist as top leaders visit Ukraine

While France’s Macron, Germany’s Scholz and Italy’s Draghi show solidarity, the bloc remains divided on how to confront Russia.

Brussels, Belgium – When the war in Ukraine began more than 100 days ago, Charles Michel, the leader of the European Council, emphasised that the European Union was ready to support Ukraine “not just in words, but with concrete and military action”.

Since then, the bloc has sent lethal aid worth 2 billion euros ($2.08bn), pledged more than 700 million euros ($728m) in humanitarian support, introduced temporary protection schemes for Ukrainian refugees, and begun discussions to coordinate “solidarity lanes” with the United Nations and other countries, to lift Russia’s blockade of Ukrainian grain.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFrench, German, Italian leaders in first Kyiv trip since war

EU signs gas deal with Israel, Egypt in bid to ditch Russia

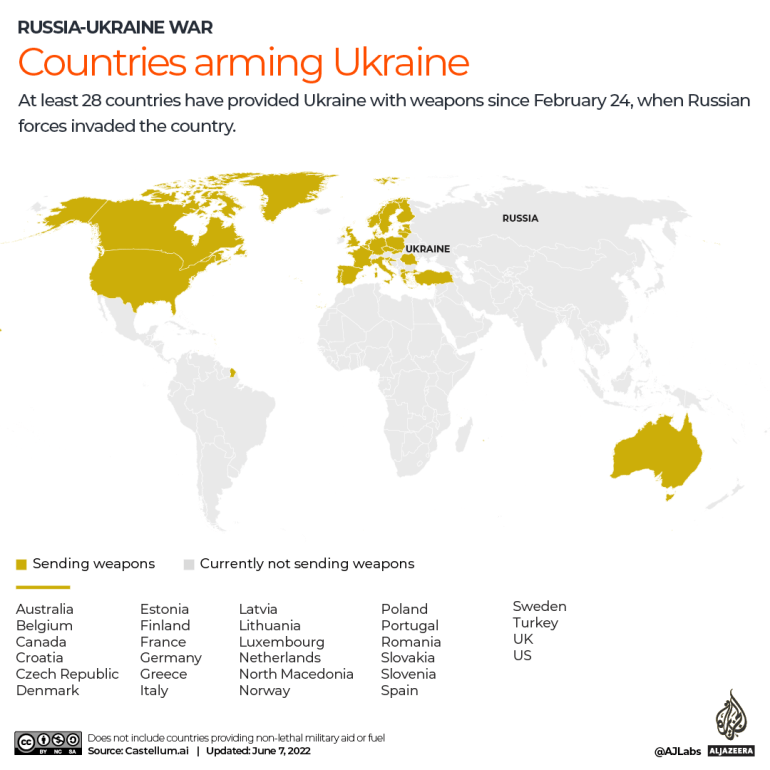

What weapons has Ukraine received from the US and allies?

EU leaders have also imposed six rounds of sanctions targeting the leadership in Moscow, oligarchs, banks and businesses, in order to cripple Russia’s economy and financial system.

And three of the most powerful European leaders – French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Italy’s Prime Minister Mario Draghi – are visiting Kyiv to meet top officials, including Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

The Ukrainian leader has welcomed the EU’s efforts and attempts to sanction Russia, while also criticising the bloc’s “unacceptable” delay in reaching a consensus on certain measures.

But Josep Borrell, the bloc’s foreign policy chief, told reporters in Brussels last month that unanimity in the EU involves accommodating the perspective of each member state.

The sixth sanctions package, in particular, saw Hungary out of step with many in the bloc, reluctant due to its reliance on Russian oil.

The EU ultimately agreed to cut 90 percent of oil imports from Russia, after striking a compromise deal with Hungary.

Harry Nedelcu, head of policy at Rasmussen Global and in charge of its Free Ukraine task force, told Al Jazeera the bloc’s response to the war should be analysed “one policy issue at a time”.

“With weapons delivery, for the first time in history, the EU has managed to mobilise quite quickly and help Ukraine. On the issue of sanctions, the bloc initially moved quickly but slowed down with decisions over important issues like weaning out Russian oil and gas because those decisions are bound to also hurt Europe,” he said.

He also highlighted that the onus of the looming food crisis required a global response.

Divisions over weapons and EU candidacy

But with Russian troops pounding Ukraine’s eastern cities, Zelenskyy has urged the West to send more anti-missile systems – which is another divisive issue, especially in Germany.

Germany’s Scholz has been repeatedly criticised for his cautious stance towards delivering heavy weapons to Ukraine.

Before Germany announced in April that it would deliver anti-aircraft systems to Ukraine, foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba in Kyiv told Italy’s La Repubblica: “There are countries from which we are awaiting deliveries and other countries for which we have grown tired of waiting. Germany belongs to the second group.”

Ukraine’s EU ambitions

Meanwhile, Ukraine remains keen to join the bloc as a member, but granting EU candidacy to Ukraine is also contentious in Brussels.

Macron has not ruled such a step out but warned it would be ineffective in the short term and involve a lengthy process.

He has instead pushed for a “European political community” that would be open to non-EU members like Ukraine and the United Kingdom, which wish to contribute to European security.

Jacob F Kirkegaard, senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund, told Al Jazeera that these divisions often centre on geographic, historic and economic links with both Russia and Ukraine.

“The Baltic countries, Poland, and others are very mistrustful of Russia. Many of them were also part of either the Soviet Union so they fundamentally believe that Russia can never be reasoned with and granting Ukraine EU candidacy should be dealt with urgently.

“Western Europe does not have the same historical experience with Russia and has been vocal about the length of the process,” he said. “Then there are the economic costs of the war, where the impact is being felt [more pointedly] southern Europe. So arguments and trade-offs are bound to happen,” he added.

Macron, Scholz, Draghi in Kyiv

Macron, Scholz and Draghi are in Kyiv ahead of a high-stakes EU leaders summit next week, which could determine the future of Ukraine’s EU membership status,

While it is not yet clear what the trio will discuss with Ukrainian officials, this visit comes after France and Germany have had some diplomatic snafus with Ukraine.

The French president’s call on the international community to “avoid humiliating Russia” over the war angered Ukraine while Scholz refused to visit Kyiv in the past after Ukraine snubbed German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier for his close relations with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Geopolitical analysts believe this visit could soothe past hiccups, and while German Marshall Fund’s Kirkegaard said the delivery of more weapons to Ukraine and the country’s EU candidacy status are at the heart of the trip, the European leaders also have a vested interest.

“It is also a strong political signal for their home countries and within the EU because Macron faces a second round of elections on Sunday, and he needs to portray his leadership as a president,” he said.

“Scholz is under a lot of pressure in Germany and the EU for his restrictive stance towards the war, so he cannot go to Kyiv and say nothing. [And] For Draghi, it’s always important for his country Italy to be viewed as an equal to France and Germany. So this is an important moment.”

Next week, EU leaders will gather in Brussels to announce their decisions on Ukraine’s EU candidacy.