‘Feeling like prisoners’: The plight of Rohingya refugees today

Five years after crackdown by security forces led to mass exodus from Myanmar, Rohingya remain stuck in ‘cruel limbo’.

Five years ago, a violent campaign by security forces in Myanmar sparked a mass exodus of about 730,000 Rohingya, who – carrying their belongings on their backs and sometimes crowding onto makeshift bamboo and jerry-can rafts – fled in search of safety. Most headed to neighbouring Bangladesh.

The violence – which included reports of gang rape, mass killings, and forced expulsion – brought renewed international attention to decades of documented persecution against the mostly Muslim Rohingya, who are largely stateless after years of what rights monitors have called systematic marginalisation by Myanmar’s government.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsHas the world forgotten about the Rohingya?

Bangladesh charges 29 Rohingya over murdered activist Mohib Ullah

But as refugees, many Rohingya have found little reprieve as they mark the fifth anniversary on Thursday of what advocates call Rohingya Genocide Remembrance Day.

A United Nations report found that attacks on Rohingya were carried out with “genocidal intent”, and in March, the United States became the first government to formally declare that the attacks constituted genocide. Myanmar has denied that any violence committed by security forces amounted to genocide.

The community remains stuck in a “cruel limbo”, according to Norwegian Refugee Council chief Jan Egeland, as refugees contend with a backslide in rights and stagnating opportunities in Bangladesh, and grim prospects of a safe and dignified return to their home in Myanmar.

If Rohingya return to Myanmar, “there is no guarantee that the cycle of violence will not repeat again,” Nay San Lwin, the co-founder of the Free Rohingya Coalition, told Al Jazeera.

But in Bangladesh, he said, “the refugees are feeling like they are the prisoners”.

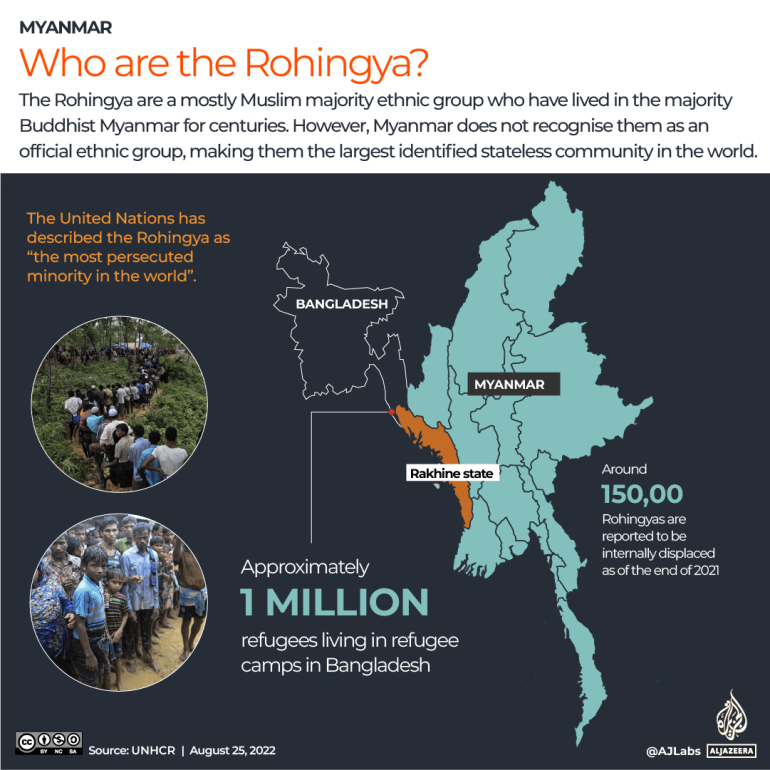

Who are the Rohingya?

-

The Rohingya are a predominantly Muslim ethnic group that trace their presence in modern-day Myanmar to the ninth century. They speak Rohingya or Ruaingga, a distinct dialect, and maintain a unique culture. They live mainly in Myanmar’s Rakhine state along the country’s western coast.

-

More than a million Rohingya have fled the country amid decades of government persecution, settling predominantly in Bangladesh, as well as India, Pakistan and Malaysia, among other countries.

-

While most Rohingya were considered equal citizens under a law passed following Myanmar’s independence from British rule in 1948, the military takeover of the government in 1962 led to the passage eight years later of the Emergency Registration Act, which limited the rights of communities viewed by the government as having foreign roots.

-

Documented persecution of the Rohingya escalated in the following years, as the military-led government sought to register all Rohingya, resulting in the first major violent crackdown on the community in 1978. During that period, about 200,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh

-

In 1982, Myanmar’s government passed a citizenship law, which defined full citizenship as based on ethnicity; specifically, being a member of one of the 135 ethnic groups the government said settled in Myanmar prior to the first Anglo-Burmese war in 1824.

-

Myanmar’s leadership has generally maintained that a distinct Rohingya ethnicity does not exist, and that members of the Rohingya community are descendants from India and Bangladesh who migrated during Britain’s colonial rule from 1824 to 1948. That position has been challenged by historians.

-

“The narrative of the Rohingya has been overtaken by fiction, with their place in Myanmar’s history expunged by a succession of military governments looking for scapegoats and aided by the country’s already strong sense of Buddhist nationalism,” wrote Gregory Poling, the director of the Center for Strategic Studies’ Southeast Asia programme, in 2014.

-

Tensions between Rohingya and other Muslim and Buddhist communities have led to further spates of state violence, most notably in the early 1990s, when about 250,000 Rohingya fled to Bangladesh, and between 2012 and 2014, when tens of thousands more left the country.

-

Meanwhile, rights groups have documented continual moves by Myanmar to render Rohingya residents stateless and marginalised, including, in 2015, the government invalidating long-held identification cards and replacing them with “national verification cards” that require, among other stipulations, that Rohingya prove three generations of residence in Myanmar and register as either “Bengali” or “Muslim”, but not Rohingya.

-

In Myanmar, rights monitors continue to record restrictions on Rohingya, which have included limits on movement, education, employment and childbearing. About 600,000 Rohingya currently remain in Myanmar, with more than 130,000 living in restrictive internal displacement camps inside the country.

What happened during the 2017 government crackdown and mass exodus?

-

The violence that preceded the largest Rohingya exodus in history began in October of 2016, following an attack claimed by a Rohingya-linked group on border police posts in Rakhine state. Myanmar said nine personnel were killed in the attacks.

-

In response, the government launched what Amnesty International called a “scorched-earth campaign” that included unlawful killings, multiple rapes and the burning of entire villages.

-

Tens of thousands of Rohingya fled to Bangladesh during the months-long crackdown, with a United Nations official saying Yangon was committing “ethnic cleansing”, defined by the UN as using force or intimidation to render an area ethnically homogenous.

-

The next wave of violence began on August 25, 2017, when Myanmar said 10 police officers had been killed in a series of coordinated attacks overnight claimed by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA). The rebel group has said the attacks were in response to abuses committed against Rohingya.

-

The resulting government crackdown, called a “clearance operation”, saw hundreds of Rohingya villages completely razed, Rohingya civilians murdered en masse, and women subjected to gang rape, according to a UN fact-finding mission report published a year later.

-

The report said the attacks were carried out with “genocidal intent” and that the country’s commander-in-chief and five generals should be prosecuted.

-

More than 700,000 Rohingya fled Myanmar in the following days, with some mothers recounting stories of babies ripped from their arms and thrown into fires by troops or nationalist groups. Witnesses and rights monitors also reported that Myanmar troops fired on those attempting to flee to the border with Bangladesh.

-

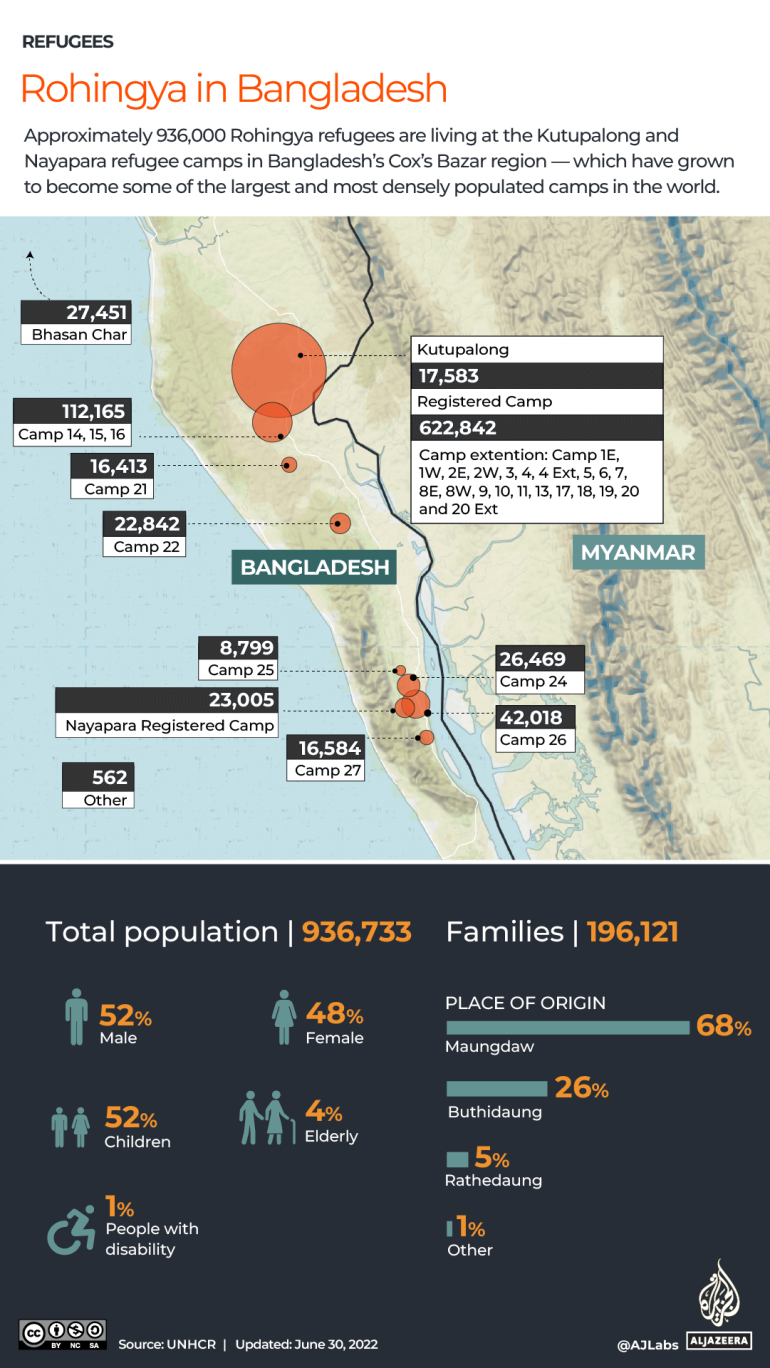

In southeastern Bangladesh, in just weeks, an array of refugee camps swelled from about 300,000 Rohingya residents to about one million, swiftly becoming the world’s largest refugee settlement.

-

The influx added significant stress to Bangladesh, where about a quarter of the population was already living in poverty, according to the World Bank. Inflation and cost of living prices have also soared across the country following the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, putting further pressure on Bangladesh’s population of about 165 million.

-

The prospect of a return to Myanmar has been made more complicated by the November 2021 military takeover of the country, which has effectively ended the country’s decade-long transition to partial civilian rule, although some analysts have argued the military repression may be softening the general public’s position towards Rohingya.

What has happened in Bangladesh?

-

According to Crisis Group’s Myanmar and Bangladesh analyst Thomas Kean, nearly all of the approximately 730,000 Rohingya refugees who fled to Bangladesh in the second half of 2017 remain in the refugee camps there, although there have been several instances of refugees attempting perilous sea journeys in hopes of finding a better situation.

-

To date, not a single refugee in Bangladesh has opted to return to Myanmar under a formal, and controversial, repatriation deal reached between the two countries in November 2017, just three months after the crackdown began, according to Kean. Subsequent attempts to convince the refugees to return in 2018 and 2019, also failed.

-

While Bangladesh has largely honoured the concept of non-refoulement, which prohibits the forcible return of refugees, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina told the UN human rights chief on August 17, 2022, that the “Rohingya are nationals of Myanmar and they have to be taken back”.

-

UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet told reporters at the time that conditions in Myanmar were “not right for returns”.

-

The government of Bangladesh has sought cooperation from China to move forward with repatriation efforts.

-

Bangladesh has also moved ahead with the controversial plan to move thousands of Rohingya refugees to the isolated and flood-prone Bhasan Char island.

-

Meanwhile, rights groups and residents have reported an increase in restrictions for Rohingya in the camps that severely “limit livelihoods, movement, and education”, according to Human Rights Watch.

-

Restrictions have included the destruction of thousands of shops in the camps in Bangladesh, where Rohingya refugees cannot legally work, and the closure of some private schools, the only form of education available beyond aid-agency provided primary schooling.

-

They have also included the construction of fences around camps and permission requirements to travel outside of one’s home camp.

-

“We cannot move freely,” Khin Maung, executive director of Rohingya Youth Association (RYA) and resident of the Kutupalong refugee camp, told Al Jazeera. “We are doing our best, but we cannot carry out our activity conveniently. We have no right to do our work freely, so we are not free at all.”

-

Meanwhile, residents have reported feeling increasingly caught between a spike in crime committed by gangs jockeying for control of the camps, and the resulting crackdown by police.

-

A series of arrests followed the killing of human rights activist and Rohingya leader Mohibullah in the Kutupalong refugee camp in September of 2021. Bangladesh blamed the killing on the ARSA.

Will there be justice?

-

For the Rohingya, anything approaching justice remains a far-off hope, although several international investigations are currently probing allegations of genocide committed by Myanmar.

-

The most prominent case has been one brought by The Gambia, a small West African country at the United Nations’ top court, the International Court of Justice, which alleges Myanmar committed genocidal acts “intended to destroy the Rohingya group in whole or in part”.

-

The case has already seen then-Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi testify in defence of the military in 2019, saying any perpetrators would be prosecuted pending an internal investigation, while denying possible crimes committed by security forces amounted to genocidal intent.

-

The Myanmar government’s investigation later said that some security forces intentionally killed or displaced civilians, amounting to “possible war crimes”, but said there was no evidence to support the genocide claims. Aung San Suu Kyi was deposed during the 2021 coup and is currently under house arrest.

-

Judges in the ICJ case have already adopted provisional measures that require Myanmar to prevent all genocidal acts against the Rohingya and to preserve evidence related to the case, while rejecting Myanmar’s opposition that The Gambia did not have standing to bring the case.

-

The ICJ case is not criminal, but a finding in The Gambia’s favour could “provide the impetus for greater international action towards justice for all victims of the Myanmar security forces’ crimes”, according to Elaine Pearson, the acting Asia director at Human Rights Watch.

-

The International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2019 also approved opening an investigation into the crackdown, arguing that it falls under ICC jurisdiction because, unlike Myanmar, Bangladesh is a signatory to the Rome Statute, which created the court.

-

Unlike the ICJ, the ICC can try individual perpetrators for international crimes. In February 2022, ICC prosecutor Karim Khan made his first investigative visit to Bangladesh.

-

The probe could be aided by a tranche of documents obtained by a non-profit war crimes investigative organisation, which appeared to show a coordinated plan by Myanmar military officials to attack and expel Rohingya and hide it from the world, as reported by Reuters news agency in early August.

-

Argentina’s justice system has also opened a war crimes investigation into the Rohingya, following a lawsuit filed by the UK-based Burmese Rohingya Organisation (BROUK). The decision falls under the legal concept of “universal jurisdiction”, which states that some crimes are so severe their prosecution is not confined to a single jurisdiction.

-

In March, the United States became the first government to declare the attacks on Rohingya constitute genocide, a largely symbolic move that could rally allies to take similar measures.