Red carpet rolled out in US bid to woo Pacific Islands from China

Washington is in heated competition with Beijing for influence among Pacific island nations.

![US Secretary of State Antony Blinken is escorted from his plane upon arrival in Nadi, Fiji, in 2022. The US hosted a two-day summit in Washington of Pacific island nations on September 28 and 29 [Kevin Lamarque/Pool via AP]](/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/AP22043128315807.jpg?resize=770%2C513&quality=80)

Washington rolled out the red carpet this week for the largest gathering of leaders of Pacific island nations ever hosted by the White House.

Leaders and representatives from 14 Pacific island states were invited to the summit on Wednesday and Thursday, and Australia and New Zealand attended as observers.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia says AUKUS pact threatens nuclear non-proliferation regime

French envoy to return to Australia amid AUKUS row

AUKUS row: French envoy accuses Australia of ‘intentional deceit’

The grouping had much to discuss: global warming and rising sea levels, economic investment and development assistance, natural disaster preparedness, maritime security, and the regional elephant in the room: China.

Both dominated and largely ignored by the United States as its “maritime back yard since World War Two”, as one writer put it, the Pacific Islands are now a chessboard of great power competition between the US and China.

And Washington is already some points down in its match with Beijing – in a game that the Pacific Islands themselves would prefer not play, experts say.

“We’re talking about a very big gap between what America wants in policy terms and what the Pacific wants,” Professor Gregory Fry, a leading expert on the region, said ahead of the summit.

While the US is focused on security owing to China’s growing presence in the region, the primary focus for the island nations is an immediate and existential threat – their ability to survive the effects of climate change.

“From the Pacific’s point of view, they want to see … action rather than just words and they are worried about America talking up the geopolitics side of things to the point where it creates more militarisation of the region,” Fry told Al Jazeera.

“The overall theme is the desire to link the Pacific into the Indo-Pacific strategy to contain China. And, in that respect, they’re not in sync at all with the Pacific Islands,” said Fry who is an honorary associate professor with the Department of Pacific Affairs at the Australian National University, and adjunct associate professor at the University of the South Pacific.

“They are interested in a strong, good relationship with America, but not embracing its Indo-Pacific strategy. That’s the key difference – they don’t want to see China as the enemy,” he said.

“A friend to all, but with limits … the limits are that the Pacific is in control,” he added.

Big dollar numbers

Reports from the first day of talks on Wednesday detailed what Washington was offering to the long list of invitees, which included the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Samoa, Tuvalu, Tonga, Fiji, the Cook Islands, French Polynesia and New Caledonia, as well as representatives from Vanuatu and Nauru.

A senior Biden administration official, who acknowledged that Washington had not paid the Pacific enough attention over the years, said “we will have big dollar numbers” for the invitees. The Washington Post put the figure at more than $860m to be invested in programmes that would aid the island nations.

An 11-point “statement of vision committing to joint endeavours” was also reported as having been endorsed by everyone in attendance.

Summit participants were also treated to a lunch hosted by US climate envoy John Kerry; meet and greets at the State Department, the US Congress, Coast Guard headquarters, and with business leaders.

Capturing the essence of the changed status of the Pacific islands a senior US official told AFP: “We’ve done meetings like this with the Pacific leaders before – they’ve normally been about an hour long in Hawaii or elsewhere.

“We’ve never done anything like this. This is unprecedented.”

China’s entry into the Pacific Islands region and the response that has evoked has also been less than ordinary.

The rush by the West to re-engage with Pacific island nations has been energetic in the past few years, and then became frenetic after China signed a security pact with the Solomon Islands earlier this year, intensifying fears of a Chinese military presence in the region.

![Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare attends a welcome ceremony with Chinese Premier Li Keqiang outside the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China October 9, 2019 [Thomas Peter/Reuters]](/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2019-10-09T022549Z_1473597141_RC13C2F21EC0_RTRMADP_3_CHINA-SOLOMONISLANDS.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C513)

The pact, which allows for Chinese security and naval deployments to the Solomon Islands, came after the nation of 700,000 people experienced political and social unrest in late 2021. The riots, which were linked to divisions within the country over how to deal with China, came to an end after the government requested Australian assistance under a longstanding security agreement.

Although the Solomons’ Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare said he does not intend to allow China to establish a military base, the US State Department said the pact with China “set a concerning precedent” as it opened the door for the deployment of Chinese forces to the region.

Pacific resets for the West

China’s focus on the region dates back at least to 2006 and the first China–Pacific Island Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Forum, which was held in Fiji and attended by China’s then-Premier Wen Jiabao.

In the decade after the forum, China pledged some $1.78bn in aid to eight countries in the region, according to reports, and China is now the region’s second largest trading partner with diplomatic ties with all countries bar four.

Countries like Australia and New Zealand, which have long been influential, appear to have only recently realised they needed to compete for relevance.

In 2017, Australia announced a “Pacific Step-up” as part of a white paper on foreign policy. The following year, New Zealand’s foreign minister unveiled a “Pacific Reset” which focused on principles for delivering shared prosperity. Even the United Kingdom, half a world away, got involved, announcing its “Pacific Uplift” in 2019.

The Australian and New Zealand policy documents cited China’s growing presence in the Pacific as motivating increased engagement, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa researcher Henryk Szadziewski noted in a report.

Then the US Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific, released in 2021, went further and addressed ways to keep the entirety of the Pacific Islands region in alignment with Washington – a policy that primarily focused on security and defence, Szadziewski wrote.

The same year the AUKUS security pact was signed between Australia, the UK and the US, which focuses on the Indo-Pacific and countering China.

There has been little attempt to disguise that the policy revamps by Western countries reflect increasing unease about China’s growing influence in the region, and the upgrading of relations with regional states has been framed as a means to both enhance security and protect an area traditionally seen as free and open to democratic nations.

While Washington and Canberra may see the Pacific Islands as the latest theatre of competition with China, the region itself is far more focused on the immediate threat of rising sea levels, and trying to avoid becoming entangled in the new power politics, Szadziewski notes.

The reason why the Pacific Islands are so strategic to the US and Australia is that their military planners do not want to concede locations that would allow the projection of sea and air power over their surrounding ocean territories.

Though China has growing economic and diplomatic heft in the region, that does not necessarily mean it will easily transform into a Chinese military presence, academics Terence Wesley-Smith and Graeme Smith say, in their book, The China Alternative.

But, “the idea” that China may leverage loans to secure access is widely accepted, and that view appears to be supported by examples of Beijing’s activities in indebted nations such as Sri Lanka, Djibouti, Cambodia and elsewhere, they add.

And yet, there are still no Chinese naval bases in the Pacific Islands region and no examples of China exerting the type of influence over regional politics that Western nations fear so much.

“It is difficult to identify examples where China caused Island leaders to take actions they otherwise would not have taken or that were contrary to their expressed interests.”

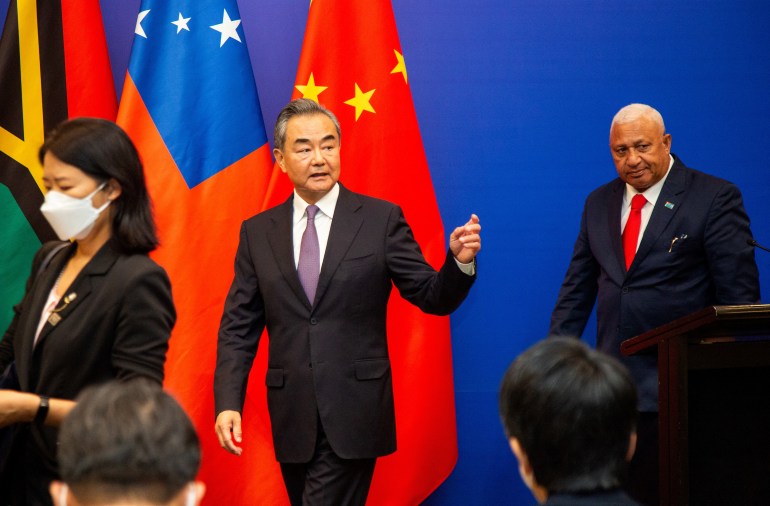

In fact, Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi and counterparts from 10 Pacific Island nations failed to reach an agreement in May 2021 on talks to establish a broad security and trade deal as the participants failed to reach a consensus on Beijing’s proposal.

Friends with benefits

Lamenting the West’s “second coming” in a region that Western nations had previously exploited as colonial powers and later used as sites for nuclear weapons testing, an opinion piece published last month in China’s English-language Global Times claimed Pacific island nations had been the target of “intimidation” not to align with China.

The behaviour of the US and its “deputy sheriff” Australia, towards the Solomon Islands, in particular, was “neo-colonialism and neo-imperialism in a new disguise”, wrote academic Chen Hong, director of the Australian Studies Centre, East China Normal University.

China, on the other hand, came to the region armed only with “respect, sincerity and transparency”, he said.

Is China just a friend to the Pacific Islands, or will it expect benefits down the road from the friendship?

That’s a question that requires an answer with an historical perspective, Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, associate professor at the Center for Pacific Islands Studies at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa told Al Jazeera.

“Historically, we see that as countries become powerful, they project themselves diplomatically. And that’s what China has been doing. And then they project themselves economically,” Kabutaulaka said.

“We’ve seen it with the US, with Great Britain, with European countries during the colonial days,” he said, adding that “it is not unlikely that in the future China will project itself militarily as well”.

“I don’t think they’re doing this just because they want to be friends to all,” he said of China.

“They’re doing this because they also know that they will be in a competition, not only economically, but also militarily in the future as a country that is emerging as powerful,” he said.

“I think they look at things in the longer term.”