For 20 years, this AIDS relief plan enjoyed broad US support. What changed?

Credited with saving 25 million lives, the AIDS programme PEPFAR now faces an uncertain future in a divided US Congress.

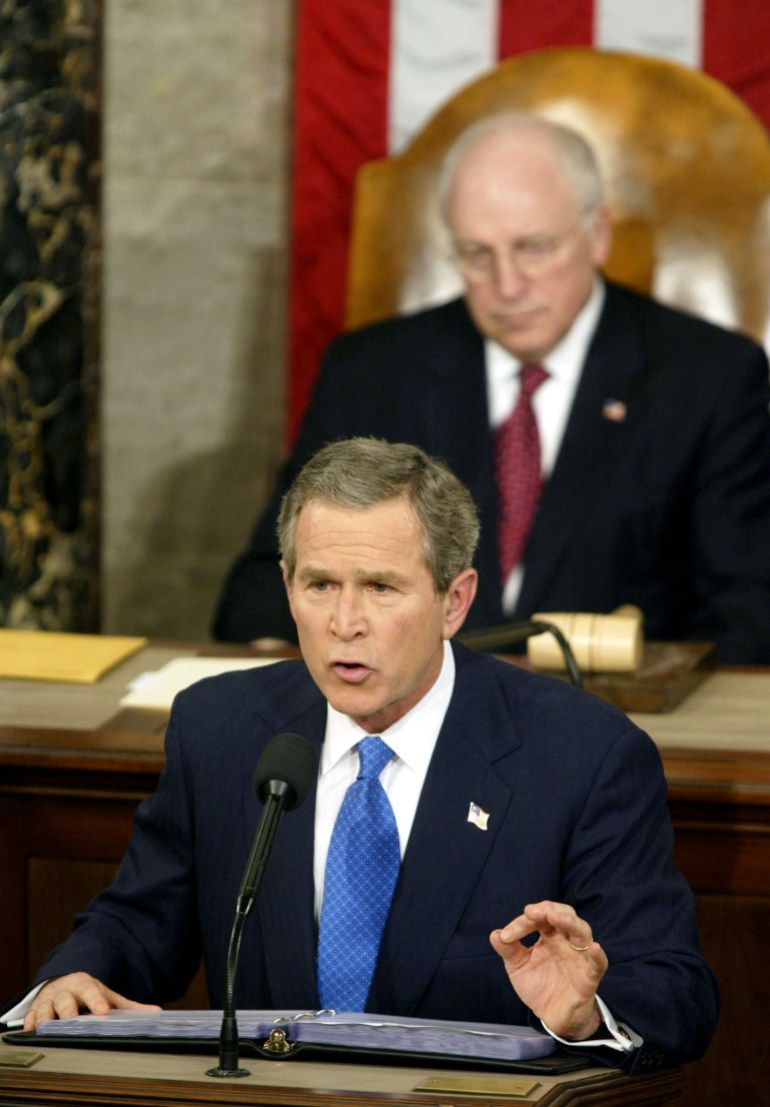

Washington, DC – The announcement caught many by surprise. It was 2003, and then-President George W Bush was standing before the United States Congress, laying out his goals for the upcoming year.

Budget cuts were high among them. “We must work together to fund only our most important priorities,” Bush, a Republican, told the packed chamber.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsThe forgotten: Living with HIV in war-ravaged Yemen

American leaked records of 14,200 HIV patients, says Singapore

But then he dropped a bombshell: He called on Congress to approve $10bn in new spending to combat AIDS in Africa.

“Ladies and gentlemen, seldom has history offered a greater opportunity to do so much for so many,” he told the lawmakers, who rose to applaud the proposal.

That proposal ultimately became the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, widely known as PEPFAR, one of the largest and most ambitious international health programmes in US history.

For the last 20 years, PEPFAR has received broad bipartisan support. Every five years, it has been renewed without incident — until now.

On September 30, Congress missed the deadline to reauthorise PEPFAR, throwing its future in jeopardy.

Lawmakers and healthcare advocates fear misinformation and dysfunction in the Republican Party may further imperil PEPFAR’s life-saving mission, as Congress stares down its next budget deadline on November 17.

“We cannot play politics with assistance so vital for public health and human rights,” Representative Ilhan Omar, a Democrat, told Al Jazeera.

Concerns over abortion

While Bush initially imagined PEPFAR would provide anti-retroviral drugs for at least 2 million people, the US State Department estimates 20 million have received treatment since the programme’s inception.

Overall, the administration of President Joe Biden said PEPFAR saved 25 million lives worldwide.

PEPFAR can continue operating at its current funding levels without congressional reauthorisation, at least over the short term. But without approval, advocates warn the programme is vulnerable to being scaled back or cut entirely.

Already, Republicans are targeting the programme with funding holds, based on the allegation that its money could be used for abortion services.

“Regrettably, it has been reimagined, hijacked by the Biden administration to empower pro-abortion international non-governmental organisations,” one Republican representative, Chris Smith, told the House of Representatives in September.

PEPFAR’s proponents deny that allegation. “PEPFAR is legally prohibited from funding abortion services,” Keifer Buckingham, an advocacy director at the Open Society Foundations, told Al Jazeera.

She pointed to laws like the 1973 Helms Amendment, which restricts foreign assistance funds from being used for “abortion as family planning”.

An emboldened party

But critics say the Republican Party has been emboldened by the 2022 decision to overturn Roe v Wade, the Supreme Court case that guaranteed the federal right to abortion.

Since the decision was handed down, Republicans have tried to further roll back abortion access, in some cases stymying routine or unrelated legislation.

Senator Tommy Tuberville, for example, has refused to approve key military appointments — a standard congressional procedure — over concerns about a Pentagon policy that allows travel reimbursement for reproductive healthcare, including abortion.

In the case of PEPFAR, Republican critics have voiced concern that the Biden administration’s strategy documents mention coordinating with organisations that promote “reproductive health and rights”, though abortion itself is not explicitly mentioned.

Republicans have also denounced a separate 2021 decision to rescind the so-called Mexico City Policy, which barred federal funding from going to any organisations that even advised patients about abortion.

But PEPFAR’s proponents believe these concerns are misguided.

The current situation is “rather an unfortunate consequence of the far-right’s crusade against abortion rights and LGBTQI+ people here in the United States and around the world”, Buckingham said.

“A small minority of outside groups are spreading lies and harmful rhetoric to score political points.”

A retreat from the world stage

Vinay P Saldanha, the director of the US liaison office for the United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS), fears PEPFAR’s uncertain future signals broader questions about US leadership on the world stage.

“If PEPFAR is not reauthorised by the US Congress in coming months, it will send an alarming signal to America’s allies and partners around the globe that America is at risk of stepping back from its global leadership on HIV and health,” he told Al Jazeera.

Analysts attribute the change in policy to a shift within the Republican Party, from Bush’s era to the present.

Whereas Bush had a hawkish approach to foreign policy, leading two overseas wars, today’s Republicans are increasingly turning away from many international issues, according to Stephen Zunes, a professor of politics and foreign policy at the University of San Francisco.

“There is a kind of isolationist trend that has emerged within the Republican Party that wants to disengage from the rest of the world,” Zunes told Al Jazeera. “There has been a trend of trying to withdraw from engagements, even in something as benign as public health. It’s pretty bizarre.”

Zunes described PEPFAR as a bright spot in the legacy of the Bush administration, which has come to be remembered primarily for its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“They did a lot of awful things in their years in office, but this saved countless lives,” he explained. “It made a huge difference. And again, it had overwhelming bipartisan support at the time.”

PEPFAR’s newfound divisiveness, he added, suggests a larger transformation.

“It just is an indication of how far to the right the Republicans have gone,” Zunes said. “The impact on human lives from this is going to be profound, as much as any war. And I think it’s illustrative of how extreme the Republican Party has become.”

Healthcare goals in jeopardy

That shift further rightward in the Republican Party has translated into other policy hurdles and delays.

Earlier this year, in the House of Representatives where Republicans hold a narrow majority, a handful of hardline party members held up budget legislation and stalled the election of a House Speaker, a role that is vital to the day-to-day business of the chamber.

But advocates have cautioned that if progress on PEPFAR is not made soon, the uncertainty could affect key international healthcare goals.

Medications exist to prevent the transmission of AIDS, and groups like the UN and the World Health Organization have set 2030 as the deadline for ending the AIDS epidemic.

But in an October report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, senior fellow Katherine E Bliss indicated that the goal could fall out of reach without the support of PEPFAR.

“If PEPFAR is not reauthorized or if the United States cuts funding along with other flows of funding for HIV, this can create a gap in service provision for people living with HIV or at risk for HIV,” Bliss said.

“Then there’s a good chance that we could see a resurgence of the virus.”

For Representative Omar, who chairs the US Africa Policy Working Group, the benefits of renewing PEPFAR are clear.

“We’ve seen with our own eyes how PEPFAR has been instrumental in saving millions of lives in Africa by providing critical support in the fight against HIV/AIDs,” she told Al Jazeera.

Its loss, she added, “would be felt across Africa and around the world”.