Tourism dreams and violence woes after Tunisia’s Djerba attack

Kais Saied’s government is working hard to minimise the recent attack on the Ghriba Synagogue, hoping to save tourism.

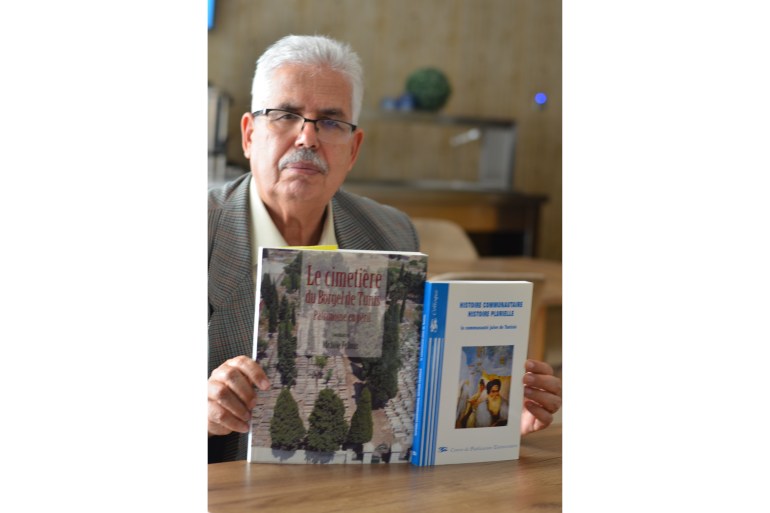

Tunis, Tunisia – Tunisian academic Habib Kazdaghli was on a bus outside the Ghriba Synagogue when the attack happened earlier this month.

Neither he nor any of his students on the coach knew what was happening. “We thought it was a fight between the policemen at first,” he told a translator later. “We didn’t know how many people were involved. We just lay on the floor of the bus in silence, for over an hour and waited.”

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsMedia rights retreat in Tunisia as gov’t tightens freedoms

Who are some of the key opposition figures targeted in Tunisia?

A Muslim by birth, Kazdaghli has been travelling to the Ghriba Synagogue on the island of Djerba every year to join with the Jewish community in celebrating the festival of Lag Ba’omer.

“We just waited there, wondering if the gunman would come on the bus. I was hoping that none of the students would contact their parents or friends from the bus, because the gunman might hear. We just waited. We didn’t know anything.”

He paused, reflecting for a moment. “So much of this is about memory. All of us experience and repress memories. Something like this, especially for Tunisian Jews, just brings it all back,” he said.

Tunisia’s Jews have been present within the country for more than 2,000 years, mixing with Indigenous Berbers, Carthaginians, Romans and Arabs. From exile within Tunisia to persecution during the country’s Nazi occupation, few of these years have been free from incident.

Nevertheless, as the story of this latest attack spread through Tunisian media, the government’s determination to frame it as a criminal assault upon the tourism industry, rather than an anti-Semitic attack on one of the region’s most vulnerable communities, became increasingly apparent.

The facts as we know them are: Shortly after 8pm, National Guardsman Wissam Khazri, after having slain another officer and stolen his weapon and ammunition, arrived at the Synagogue, after having travelled more than half an hour overland by quad bike to reach it. Once there, the interior ministry said, he opened fire apparently indiscriminately, killing two pilgrims, cousins Avial and Ben Haddad, and two police officers, as well as wounding several more.

Two minutes later, he was shot dead by officers.

However, over the next 24 hours, the government pursued a course of minimising the anti-Semitic nature of the attack, while emphasising the minimal disruption caused to the country’s tourism industry, of which the island of Djerba contributes a significant amount.

The problem, Kazdagli said, was not that the government was unused to responding to crises, it was rather that they didn’t know how to respond to this crisis. “That the attack targeted Jewish people and that it took place at El Ghriba” left them paralysed, he said. “They don’t know how to explain it. They don’t know how to make it make sense to people,” he told a translator.

Addressing the country a day later, President Kais Saied characterised the attack as “criminal”, rather than “terrorist”, in nature, a term he deploys with relative ease against his opponents and critics. There was no mention of the gunman’s anti-Semitism or his specific targeting of the Jewish community. In a brief news conference a couple of days later, the interior minister informed journalists of the attacker’s name and that the ministry regarded the attack as premeditated. Little more was added.

The truth, according to observers such as Hamza Meddeb of the Carnegie Middle East Centre, is that, despite reports of four arrests since the shooting, the reality, including the race of those targeted, is simply too messy.

“I can understand why they don’t want to call this a terrorist incident,” he said. “It raises too many questions. Let’s not forget the attacker was a police officer, we know nothing of this guy’s background. Had he been radicalised? If so, by who? How extensive was his network? If they say he’s an anti-Semite, how extensive are those sentiments within the police? More significantly, how extensive are those sentiments across society? That’s an uncomfortable question.

“It’s much easier to simply dismiss the attack as a criminal act and move on,” he said.

Currently, across Tunisia, the gaps in supermarket shelves are one of the best indicators of the variety of staple household goods the government subsidises. With every year that passes, the burdens upon the Tunisian economy grow heavier as the national currency, the dinar, shrinks further. Critically, healthy tourism revenues, and the hard currency they bring, might go some way to giving the president and his ministers room to manoeuvre in their negotiations over a potential bailout by the International Monetary Fund.

Against this grim backdrop, tourism, one of the few bright economic bright spots in Tunisia’s endless night, held out at least the seed of optimism. In a normal year, according to Tunisian economist, Raddhi Meddeb, tourism would contribute some 7 percent to Tunisia’s gross domestic product (GDP). Factoring in the ancillary industries, from farming to catering, that number doubles to 14 percent. Receipts so far, up 60 percent on the same period last year, already point to a promising summer.

“In terms of tourism, Tunisia generally competes in terms of price. Factor in the financial crisis taking place within Europe at the moment, as well as the instability in [competitor] Turkey and you’re looking at Tunisia becoming one of the key destinations for European tourists this summer,” Meddeb said.

However, all of this stands to be derailed by talk of a violent attack against a community considered so vulnerable that a large portion of the Tunisian security services is deployed every year to guard them.

“We know that for what we call, sun and sand tourists, safety is a significant feature,” Grzegorz Kapuscinski, a senior academic in tourism management at Oxford Brookes University, said.

“And it’s not really about just one attack, but the frequency of incidents and the collective awareness of them,” Kapuscinski said. “So yes, I can understand why the Tunisian government has chosen to handle it this way. With that said, I’m not sure it will work. I think full transparency is always the best idea.”

However, hoping that the world would simply forget about it and move on is looking less likely.

A further stumbling block for Tunisian efforts is an investigation launched in France with which Ben Haddad shared nationality, (Avial Haddad also carried an Israeli passport) which may not take as much heed of Tunisian sensitivities as President Saied might hope.

For now, however, the effect is more immediate. The families of the synagogue’s defenders, as well as those of Ben and Avial Haddad, all have to reconcile themselves with a savage and entirely unexpected loss. For them, at least, the summer can wait.