‘Books need time’: Tan Twan Eng’s new novel opens door on history

Malaysian Booker shortlisted novelist has published his first book in 10 years; a tale of love and betrayal in colonial Malaya.

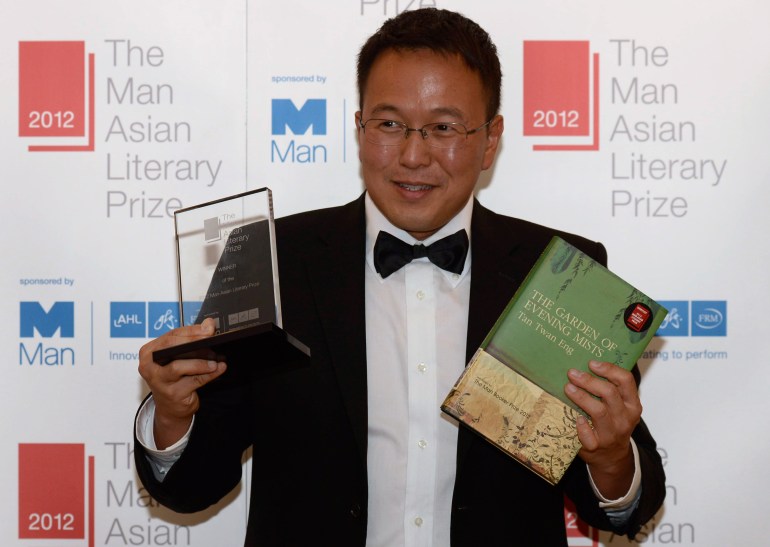

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia – It has been a decade since Tan Twan Eng’s second novel, the Garden of Evening Mists, seduced readers around the world and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and a slew of other literary awards.

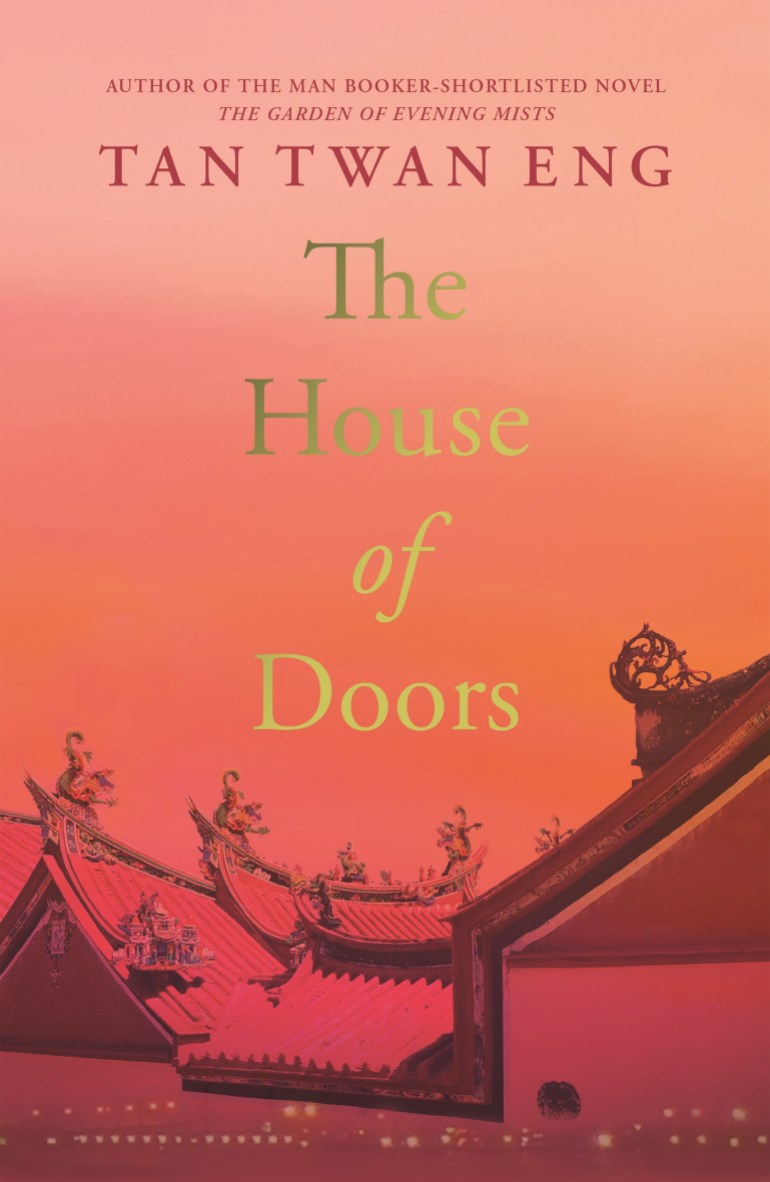

This month the bestselling Malaysian author finally published his third book, The House of Doors.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMichelle Yeoh’s success masks struggle of Malaysian film industry

How Behrouz Boochani is changing the narrative on refugees

Philippines: Artists protest authoritarianism through their work

“It’s been slow,” Tan acknowledges with a rueful smile in a video call from his study in South Africa.

Dressed in a suit and sitting at a desk, he looks more like the lawyer he once was than the stereotypical writer, but the shelves on the walls behind him are lined with books.

“There are lots more lying around on the floor,“ he laughs.

One reason for the slow progress on the new novel was the whirlwind of publicity and speaking engagements that accompanied the Booker nomination.

But as the promotional engagements came to an end and Tan sat down to work, it became clear that the kernel of a project he had expected to become his third novel was too big.

Instead, he returned to an idea based around Chinese nationalist revolutionary Sun Yat Sen, who spent time in Penang in the early 20th century raising funds from his headquarters on Armenian Street in the now World Heritage-listed historic centre of George Town.

But bringing the novel to life proved more of a struggle than Tan had anticipated.

“I thought I didn’t have to do much research for this one,” says Tan, who was born in Penang and whose parents lived on Armenian Street in the 1950s.

“For a variety of reasons, it wasn’t working,” he says, admitting there were times when he could not face opening his laptop because “I knew it was going to be terrible and I didn’t know what to do”.

At one point, Tan even considered abandoning the book altogether.

“The story wasn’t working. The characters weren’t coming alive. My structure was all wrong,” he explains.

It took an intervention by his agent — who suggested Canongate’s publisher at large, Francis Bickmore, take a look at the manuscript — to restore Tan’s confidence in what he had written.

“Bless him, he loved it straight away,” Tan recalls of Bickmore’s response. Together, they worked on crafting the work into shape, mainly by addressing the structure and moving some chapters around.

The former Kuala Lumpur lawyer first burst onto the global literary scene with his 2007 debut novel, The Gift of Rain, which was set in Penang during the Japanese occupation that heralded the end of British rule. Long-listed for the Booker, it inevitably drew comparisons with the work of fellow Malaysian writer Tash Aw whose first novel, The Harmony Silk Factory, was set in Penang on the brink of occupation and had also been long-listed for the prize two years before.

Unsurprisingly, Tan’s work springs from a passion for history, and Malaysia’s sometimes painful past.

While there has been much discussion of fiction being mistaken for fact, Tan sees the historical novel as a starting point for investigation and debate.

“The novel doesn’t preach to you or hector you,” he says. “You make up your mind how you want to interpret the past. If you get upset or uncomfortable or angry about something it’s a good spur to find out more about that particular event.”

Malaysia achieved independence in 1957, leaving behind nearly 450 years of colonial rule, first by the Portuguese, then the Dutch, and finally the British.

The British carved out plantations from the dense jungle, turning the country into the world’s biggest exporter of rubber, and developed a booming tin industry, with legions of ethnic Indian and Chinese migrants keeping the colonial economy humming.

A system of divide and rule helped the British maintain control of the country’s increasingly diverse population while the colonial expatriates lived a world apart, trying to create a little England in the tropics, complete with its clubs, churches and cloying social structures.

Women, for instance, were not allowed in the bar at Kuala Lumpur’s tudor-style Selangor Club, situated in the heart of Kuala Lumpur and the favoured meeting point of the colonial-era elite.

The club remains there today, although the field the British called the ‘padang’ and used to play cricket is now known as ‘Dataran Merdeka’ or Independence Square.

“I’m interested in how differently they did things then, but also how similarly; its relevance for today,” Tan says. “You have to write what speaks to you.”

Colonial scandal

The House of Doors is set in the 1920s, and Tan found the element that would make the book work was the author, Somerset Maugham, and his fictionalised account of the downfall of Ethel Proudlock — the wife of a Kuala Lumpur head teacher who was tried and convicted of murder in a case that scandalised the city’s conservative colonial society.

So too, did Maugham’s account of it, The Letter, which was published in his acclaimed collection of short stories, The Casuarina Tree, to the horror of those who had welcomed Maugham into their homes.

While Sun, Maugham and Proudlock are all real people, it is the fictional characters — and in particular Leslie Hamlyn, the Penang-born British expatriate wife who comes to reveal her secrets and those of Ethel Proudlock to Maugham — who help stitch the narrative together.

As with his two previous novels, The House of Doors is immensely evocative of time and place, the rickshaw riders’ “ribcages hollowed by opium”, a sea that is “emerald and turquoise and chipped with a million white scratches” and the shadows of clouds that “bruise the earth”.

Tan says he was “relieved” by the early reviews of the novel.

The United Kingdom’s Financial Times described the book as “expertly constructed, tightly plotted and richly atmospheric”. The Literary Review said that Tan had “woven a superb, quietly complex tale of love, duty and betrayal.”

Tan has spent the last few months as one of this year’s five judges for the International Booker Prize, awarded to the best work of fiction translated into English and published in the UK and Ireland.

This year’s winner will be announced in London on May 23.

“It’s been eye-opening,” Tan says of the judging process. “I discovered a lot of books that I thought… Wow… these books should be more widely known.”

Admitting the ideas for his own books do not come easily, he is already thinking of what he might write next.

“I might go back to my old project,” Tan says.

He hopes it will not be 10 years before his fourth novel is out in the world, but wonders how some writers are able to knock out a book every year or two.

“Some books need time. Some writers need time.”