‘Deteriorating security’: What led to Niger’s coup and what next?

Niger plotters cited worsening insecurity in their takeover speech, a go-to reason for recent coups in the Sahel.

On Wednesday, elements of Niger’s presidential guard began the process that eventually led to the overthrow of Mohamed Bazoum, president since April 2021.

Army spokesperson Colonel-Major Amadou Abdramane said in a statement broadcast on a state-run television channel that “the defence and security forces … have decided to put an end to the regime you are familiar with”.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 823Russia-Ukraine war: List of key events, ...

Spain pledges 1 billion euros of military aid to Ukraine in 2024Spain pledges 1 billion euros of ...

North Korea says rocket carrying satellite exploded mid-flightNorth Korea says rocket carrying ...

“This follows the continuous deterioration of the security situation, the bad social and economic management,” he added. The country’s borders have been closed and a nationwide curfew is in place.

A seated Abdramane was flanked by nine other officers wearing fatigues – members of a group which is calling itself the National Council for the Safeguarding of the Country – as he read out his statement.

In March 2021, a military unit tried unsuccessfully to seize the presidential palace days before Bazoum, who had just been elected, was due to be sworn in.

Bazoum’s election a few months earlier was the first democratic transition of power in a state that had witnessed four military coups since independence from France in 1960.

Wednesday’s successful mutiny also has implications for a region usually derided as a “coup belt”: it was also the sixth successful coup in West Africa since 2020 after two apiece in neighbours Burkina Faso and Mali as well as one in Guinea.

Usurpers in those states also blamed the ruling governments there for failing to stem a tide of insecurity that has taken over the Sahel since 2012.

In the August 2020 coup in Mali, the soldiers behind it called themselves the National Committee for the Salvation of the People. “We are not holding on to power but we are holding on to the stability of the country,” said one of them, Ismail Wague, Mali Air Force’s deputy chief of staff.

In January 2022, a group of Burkinabe soldiers calling itself the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration or MPSR – according to its French language acronym – evoked deterioration of security, too, as they deposed President Roch Kabore and suspended the constitution.

Why has it come to this?

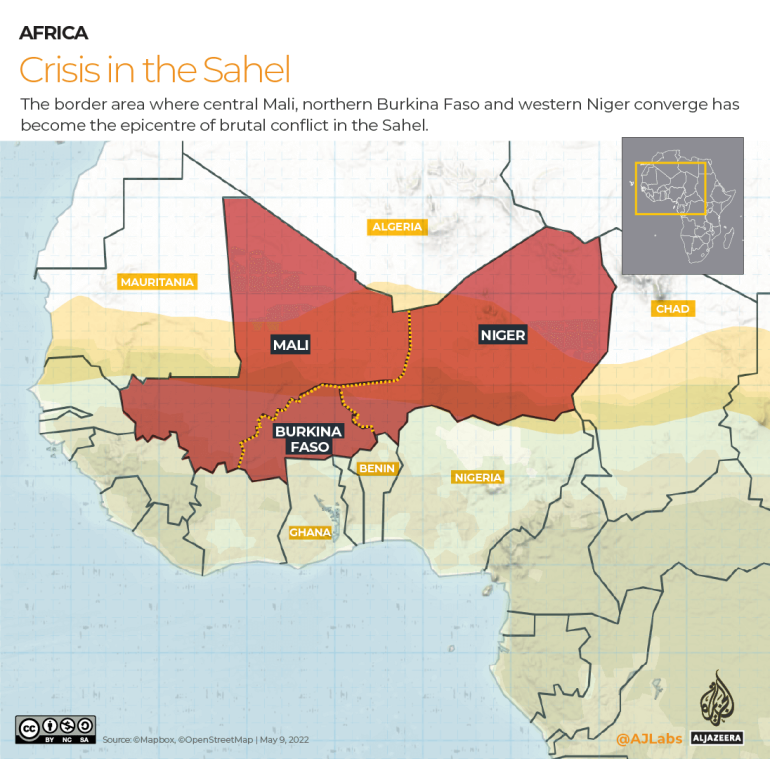

Primarily, the Sahel consists of Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad and Mauritania, a quintet known as the G5 Sahel. But parts of Senegal, Nigeria and the two Sudans are also included in varying categories.

A NATO-led takedown of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 triggered a massive inflow of small arms, mercenaries and armed groups into the Sahel.

That helped energise Boko Haram in northeast Nigeria which began waging war against the state after the death of its founder Mohammed Yusuf in 2009, to spread its tentacles to parts of Chad, Cameroon and Niger.

But just as importantly, many Touareg fighters who had sided with Gaddafi during the Libyan civil war returned to Mali with plenty of weapons. In 2012, they resuscitated a rebellion that had begun as secessionist agitations in the ’60s in Mali’s northeastern Kidal region and Niger’s northern Agadez region.

Over time, the border area where central Mali, northern Burkina Faso and western Niger converge has become the epicentre of brutal conflict in the region.

Frustration with the democratic government’s handling of the security situation and the perceived ineffectiveness of French soldiers, who were initially welcomed in 2013, led to a change of guard in Bamako and soured relations with Paris which then withdrew its troops.

In Burkina Faso, similar frustration led to a coup d’etat that again worsened relations with France.

Across French-speaking West and Central Africa, anti-French sentiment bubbling under the surface began crystallising publicly, leading to demonstrations by citizens in favour of the coups and against the foreign troops.

So Niger was seen as a beacon of stability – and indeed it presented itself as one in the Sahel, so Western countries courted its partnership, eager to protect their economic interests and discourage African migration to Europe.

Meanwhile, Niger used Western aid to boost its military strength; military bases belonging to France and the United States are on its soil. In Niamey, Germany runs a logistics outpost and like Italy and Canada, is involved in the training of Nigerien special forces.

And experts believe Bazoum’s predecessor Mahamadou Issoufou stepped down after his constitutionally mandated two-term presidential limit to avoid the possibility of a coup.

“Issoufou knew that he only had to clear a minimum bar to appear like a democrat,” said Alex Thurston, assistant professor of political science at the University of Cincinnati.

But opening his arms to the West was a risky gambit, analysts say. Familiar complaints of incompetence in governance overall and of corruption within and beyond the military also crept in.

“The [attempted] coup fits into a long pattern of inability by the political class to speak to the economic challenges and the security and political instabilities in the country,” Emmanuel Kwesi Aning, professor of peacekeeping practice at Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Accra, Ghana, told Al Jazeera. “That, nevertheless, does not justify the attempted coup,” he said.

What happens next?

The coup attempt prompted a slew of condemnation from the international community, including the United States and bodies like the African Union and the West African regional bloc, Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

“The ECOWAS leadership will not accept any action that impedes the smooth functioning of legitimate authority in Niger or any part of West Africa,” said Bola Tinubu, Nigeria’s president and chair of the regional bloc in a statement on Wednesday.

“We will do everything within our powers to ensure democracy is firmly planted, nurtured, well rooted and thrives in our region,” said Tinubu, who dispatched Patrice Talon, president of neighbouring Benin to Niamey to help resolve the situation.

The outcome of those negotiations remains unknown.

While Bazoum remains defiant and has promised to protect “hard-won” democratic gains in the country despite his removal, it also remains uncertain what happens next, for Niger’s people but also its Western partners.