Climate change displacement: ‘One of the defining challenges’

As volatile weather patterns continue, some communities are being forced to move to survive.

Climate-induced catastrophes have devastating global effects, from intense heatwaves to heavy rainfall.

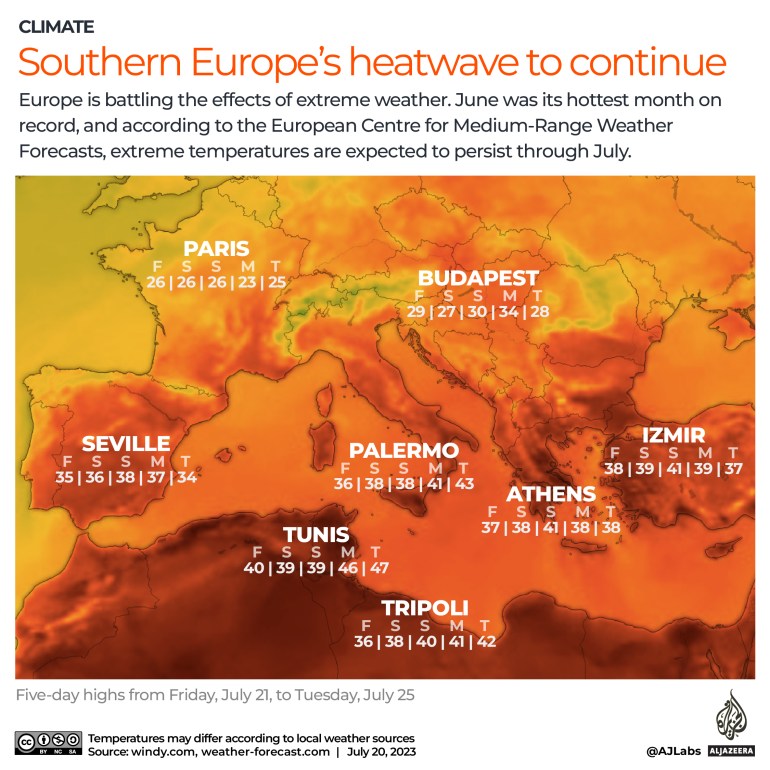

In 2023, record-breaking heatwaves hit much of continental Europe and resulted in wildfires and flash floods that took lives.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsShould the developed world pay for climate change?

Is climate change fuelling Idalia and other hurricanes?

African leaders seek global taxes for climate change at Nairobi summit

In China, typhoons have forced school closures and evacuations. Meanwhile, in South Asia, rising temperatures and longer monsoon seasons are increasing cases of mosquito-borne dengue fever.

Last week, the United Nations published a new report on climate change and found that countries agreeing to fight global warming by signing the Paris accord had only made limited progress.

The 2015 Paris Agreement is a legally binding treaty to limit the global temperature increase this century to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius. Experts have warned past that level, the problems arising from widespread flooding, droughts and heatwaves could become unmanageable.

As weather patterns continue to become more volatile, the prospect of climate-induced migration is increasingly becoming a core issue.

According to the UN, extreme weather events, including heavy rainfall and droughts, have already caused “an average of more than 20 million people to leave their homes and move to other areas in their countries each year”.

Here’s everything you need to know about climate-induced migration:

How much of an issue is climate displacement?

Climate-induced migration is a movement pattern caused by the effects of climate-related disasters, including droughts leading to a food and farming crisis.

Ezekiel Simperingham, global lead on migration and displacement for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), told Al Jazeera: “Climate-related migration and displacement is becoming one of the defining challenges that we are seeing as a humanitarian network. We’re not just seeing it in one region … we’re seeing it across different regions. We’re seeing it manifest in very different ways.”

According to Climate Refugees, an organisation documenting the growing threat of climate displacement, climate change can exist as a “threat multiplier”.

“Exacerbating existing risks and creating new ones like food and water insecurity and competition over resources, which contributes to conflict and compound displacement,” it said.

For those who fled conflict and seek refuge in a new country, climate change will direly affect an already displaced population.

Eujin Byun, a spokesperson for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), told Al Jazeera western and central Africa, which suffer from frequent flooding, are also dealing with continuing conflict.

“So its not just one factor pushing this vulnerable displaced population, but it’s also that very complex dynamic that they have to keep moving around,” Byun said.

Climate-induced displacement vs ‘climate refugees’

While many climate-displaced peoples are also fleeing conflict, climate organisations are wary of referring to them as climate refugees and find the phrase limiting.

In international refugee law, the term “climate refugee” does not exist, and that type of migration does not qualify for protection under the 1951 Refugee Convention.

Under the UN convention, a refugee is defined as a person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of [their] nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to … return to it”.

Byun explained that referring to a person as a climate refugee limits the complex situation because the term would mean that a person fled strictly because of a climate event and not from other issues affecting the country.

“I think part of the reason why people are grappling with the terminology, and I think part of the reason why we try and have a more expansive approach is because we’re also seeing that people are moving in very different ways because of climate change,” Simperingham added.

Sanjula Weerasinghe, coordinator of migration and displacement at the IFRC, also told Al Jazeera that only some people are moving in the same way that refugees do, and more often than not they’re making decisions based on various factors.

“Some of it will be related to climate, but some of it may be related to the governance around where they live. Some of it relates to their livelihoods, which may be impacted by climate, but preexisting conditions and how they were able to or unable to earn an income,” Weerasinghe said.

“To just highlight the climate as the key reason why is not entirely accurate.”

Where are people moving to?

According to the Migration Data Portal, in 2022 about 8.7 million people in “88 countries and territories were living in internal displacement as a result of disasters”.

The top five countries with the highest levels of internally displaced people (IDPs) were Pakistan, the Philippines, China, India and Nigeria because of weather-related issues such as floods and storms.

Byun said there are two displaced populations: those internally displaced and those who left for neighbouring countries.

“They [people affected by climate change] don’t really want to cross the Mediterranean because they still have their farm to keep, they still have property back in their country,” she said.

So narratives of a “flood of refugees” coming to the Global North are not the reality and are not helpful in understanding climate migration, Simperingham added.

What can be done?

As climate-induced migration becomes one of the defining humanitarian struggles worldwide, the UN has said the world must invest in preparedness to “prevent further climate-caused displacement”.

The UN has also created a Refugee Environmental Protection Fund to invest in reforestation and clean cooking programmes in climate-vulnerable areas.

Simperingham explained one of the opportunities related to climate migration is that efforts can start before people have moved to address their humanitarian needs.

“What I mean is better understanding the communities, the parts of the world that are at the highest risks of the impact of climate, especially where they are intersecting with other risks and vulnerabilities”, he said.

But, some argue there needs to be more discussion on solutions from the global community.

“What can be done to stop that same situation happening again? What are the options for people to move within their country and sustain their resilience and wellbeing? So that’s an area – and that’s an agenda that needs a lot of attention,” Weerasinghe said.