Fear grips refugees after UNHCR says it will close Sri Lanka operations

Hundreds of refugees and asylum seekers face an uncertain future as the UN agency announces closure of its country office this year.

Colombo, Sri Lanka – Sixteen-year-old Ohnmar* has never experienced the joys of attending school, the excitement of playing with friends during recess or simple pleasures of life like savouring a satisfying meal.

Ohnmar, a Rohingya, was born “stateless” because Myanmar has not granted citizenship to members of his community since 1982. He fled to Bangladesh with his family during the Myanmar military’s genocide against the Rohingya in 2017 and has been a refugee since.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUNHCR: 569 Rohingya died at sea in 2023, highest in nine years

Six years of Rohingya exodus: Food crisis and fears of a ‘lost generation’

Why Sri Lankan Tamil refugees in India attempted mass suicide

Two years later, his father died of illness. In December 2022, the rest of the family left a refugee camp in Bangladesh hoping to reach Indonesia by boat. But the boat’s engine failed during the perilous journey, and his mother and three brothers drowned.

Ohnmar, along with nearly 100 other survivors, were rescued by the Sri Lankan navy off the island nation’s northern coast. Since then, he has been living in Sri Lanka as the only surviving member of his family.

The teenager currently shares a home with other refugees and has no one to take care of him. He said he has not had a proper meal in two days.

The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) had granted Ohnmar a monthly allowance after he was released following a three-month detention after being rescued. He would use the money to buy meals and other basic necessities.

But the UNHCR scrapped the allowance for refugees in December, so now Ohnmar often goes hungry for days. He depends on meals shared by other refugees.

“Please help me settle in another country permanently. Otherwise, I will starve and become homeless,” Ohnmar told Al Jazeera at Panadura, a town 27km (17 miles) south of the capital, Colombo.

Current status of refugees

Sri Lanka is home to hundreds of refugees like Ohnmar desperate to settle down permanently in another country. But they fear time is running out.

Sri Lanka is not a signatory to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and its 1967 protocol – two key legal documents that protect transnational rights. Moreover, there is no domestic law or mechanism to deal with refugees or asylum seekers on the island.

This has made Sri Lanka a transit point for refugees until the UNHCR helps them resettle in another country.

But the UNHCR told Al Jazeera it will close its Colombo office in December because most of the people displaced internally during Sri Lanka’s long civil war had returned to their native places.

“The phasing-down process will continue through the end of 2024, and UNHCR will maintain a liaison presence in Sri Lanka from 2025 onward,” UNHCR spokesperson Liania Bianchi told Al Jazeera in an emailed response.

The UNHCR is the only organisation in Sri Lanka that has handled the process of registering refugees and filing applications on their behalf with other countries for permanent resettlement. It also offered them monthly allowances “tailored to individual needs” and scholarships for children to attend school.

Refugees and asylum seekers fear they will be stranded when the UNHCR wraps up its operations. According to the agency’s latest data from mid-2023, there are 567 refugees and 224 asylum seekers in Sri Lanka, most of them Pakistanis.

A large number of Pakistani refugees belong to the Ahmadi Muslim sect, which has been long persecuted for religious reasons and considered non-Muslims under Pakistani law. There are also Pakistani Christians and Shia among the asylum-seeking population.

Some of these refugees have been unable to leave Sri Lanka for nearly a decade or more because their applications have been rejected by host countries. The UNHCR does not allow refugees to choose a country to settle in permanently. They have to wait until it files applications with countries likely to accept them.

‘Help us resettle before leaving’

Yuzana*, 18, last saw her family when she left a refugee camp in Bangladesh in 2022. She left her family behind when she moved out of the camp, hoping it would increase her prospects for a better life.

Since Rohingya are stateless, they do not have passports and cannot travel by air. In their search for safe and permanent shelters, they are forced to undertake dangerous journeys by sea on rickety boats packed beyond capacity.

Like Ohnmar, Yuzana was also among the refugees rescued by the Sri Lankan navy in December 2022 after their boat to Indonesia had engine trouble.

“I have never been to a school. My only request is to help me move to a country permanently, so that I can start studying. Without that, I am clueless about my future,” Yuzana told Al Jazeera. “I can’t stop thinking of my family. I want to meet them soon.”

Yuzana, a minor at the time of her rescue, was first placed at a detention centre with other refugees and later moved to an orphanage from which she was released this month.

“The UNHCR handled all my expenses since I came here [Sri Lanka]. They even gave me a voucher to buy essentials. I am surviving using that. But now they have stopped giving the allowances. I don’t know what to do,” she said.

Khine*, 51, another Rohingya rescued in 2022 along with his two sons and grandchildren, said he was grateful to the Sri Lankan navy and the UNHCR for helping him stay in the country.

“We were kept at a detention centre for three months. After we were released, the UNHCR gave us monthly allowances, which was helpful to me. Now it is difficult to survive without the allowance,” he said.

Khine said the UNHCR must help refugees move to another country before closing its office in Sri Lanka.

“The early days of my life are over, but what will happen to my kids and grandkids? Without citizenship, there is no hope,” Khine told Al Jazeera. “How can the UNHCR leave without solving our problem? We can’t go back to our country.”

‘Give us the allowance’

As living costs soar, exacerbated by a severe economic crisis in Sri Lanka, the UNHCR’s decision to stop the monthly allowances for refugees and scholarships for children in primary grades has come as a double whammy.

The cost of essentials including cooking gas, food and utilities has risen after the government increased value-added taxes up to 18 percent in January. Crops destroyed by heavy rains have also led to an increase in food prices.

Carrots, for instance, are being sold at 1,975 Sri Lankan rupees ($6) a kilogramme (2.2lb), up from 200 rupees ($0.6) a year ago, central bank data show.

Worse, refugees are legally barred from working in Sri Lanka, forcing them to rely on the UNHCR allowance or donations from charities – both barely enough to meet their needs.

In the coastal city of Negombo, about an hour’s drive from Colombo, Fareedun Saeed; his wife, Riffat Fareedun; and their two daughters are struggling to make ends meet.

The UNHCR initially granted them a monthly allowance of 22,000 rupees ($68) before increasing it to 43,000 rupees ($134) amid skyrocketing inflation in 2022.

“We used the money to pay the rent, buy food, and pay our electricity and water bills. Now they have stopped the allowance. I don’t know what to do,” Saeed told Al Jazeera.

For more than a decade, they have been living in a small house with barely enough space to move around. With food becoming increasingly expensive, the Fareeduns are surviving on roti, a flatbread they have with lentil curry or eggs once a day.

“My daughters say they can’t eat roti every day. But I have to convince them to eat this. I don’t eat much. We give our food to our daughters,” Fareedun, a certified beautician, told Al Jazeera.

A member of the Sayed caste, Fareedun married Saeed, who hails from the Sheikh caste. Intercaste marriages are often considered unacceptable in some parts of Pakistani society.

Scars on Fareedun’s left forearm and Saeed’s head remind them of the days they were attacked for their marriage after it was opposed by their families.

“We are appealing to all countries: Please grant us resettlement. I can’t go back to Pakistan. They will kill me. I’d rather die here,” Fareedun said, adding that her applications for immigration to Australia and the United States were rejected.

After the UNHCR allowances were scrapped, Fareedun has been skipping her high blood pressure medication and often falls sick as a result.

Both her daughters – 14-year-old Fathima Fareedun, a ninth-grade student, and 12-year-old Aysha Fareedun in grade seven – received UNHCR scholarships to pursue their educations, which have now been scrapped.

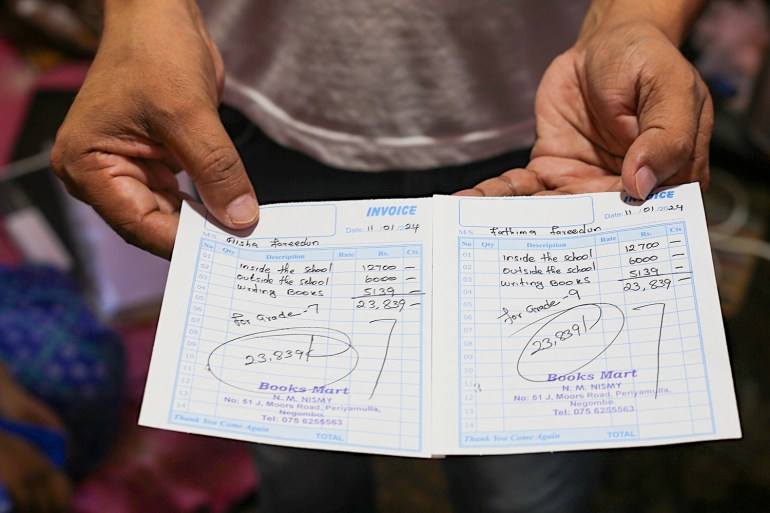

Saeed showed two quotations each of nearly 24,000 rupees ($75) that he received from a bookshop to buy books for his daughters. “How can I buy this when I don’t have an income? They don’t allow us to work. Soon, my daughters won’t be able to go to school.”

Fathima was three when she arrived in Sri Lanka. “At times, I haven’t gone to school because we couldn’t pay for transport,” she told Al Jazeera. “Please help us resettle in another country. I want to study and become a doctor.”

What happens next?

The UNHCR said it will coordinate with Sri Lankan authorities after closing its office to ensure refugees and asylum seekers are protected and not sent back to countries where they are at risk of persecution.

“UNHCR will continue to advocate with the authorities for them to ratify the 1951 convention [and] develop a national asylum system in the country,” Bianchi told Al Jazeera.

“UNHCR will also continue to work to ensure that refugees already identified for resettlement continue the departure process.”

But Ruki Fernando, a refugee rights activist, said their basic rights are being violated because they cannot work and their access to education is hampered.

“Sri Lanka must have a domestic law and mechanism to process asylum applications and offer permanent resettlement and citizenship to at least a small number of people,” Fernando told Al Jazeera.

“The government should provide housing to these refugees and allow their children to be part of the country’s free education system.”

Refugees and asylum seekers have occasionally been threatened, attacked and deported from Sri Lanka. The UNHCR’s planned departure has heightened fears of more abuse and deportations.

In 2014, the Supreme Court permitted authorities to deport several Pakistani asylum seekers after the government accused them of committing crimes and spreading malaria.

Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said at the time that at least 18 malaria cases were detected among asylum seekers that year. The cases were discovered when Sri Lanka had no local malaria infections and was awaiting a malaria-free certification from the World Health Organization, the ministry said.

The UNHCR at the time accused Sri Lanka of violating international laws.

“When the previous deportations happened, UNHCR was the key agency which intervened on behalf of refugees and asylum seekers. When the UNHCR is absent, there is a question of who will intervene on behalf of them,” Fernando said.

Chomden*, 20, a widow and mother to a five-year-old daughter, left Myanmar in 2017. She is sceptical about her future after the UNHCR stopped her monthly allowance of 31,000 rupees ($96).

“If the UNHCR is planning to close the office without a proper solution, we can’t imagine what will happen to us,” she told Al Jazeera.

“Rather than leaving us stranded here, it’s better if they can repair our boat and push us back into the ocean. At least we will die there quickly.”

*Some names have been changed to protect identities.