What is life like inside the world’s biggest refugee camp?

Six years after Myanmar's brutal crackdown, Al Jazeera explores the current living conditions in Rohingya refugee camps.

It is monsoon season in Bangladesh. Every year from June to October, heavy rainfall befalls the country. For one million Rohingya refugees housed near the base of the country’s spine, there is little defence against the elements - natural or manmade.

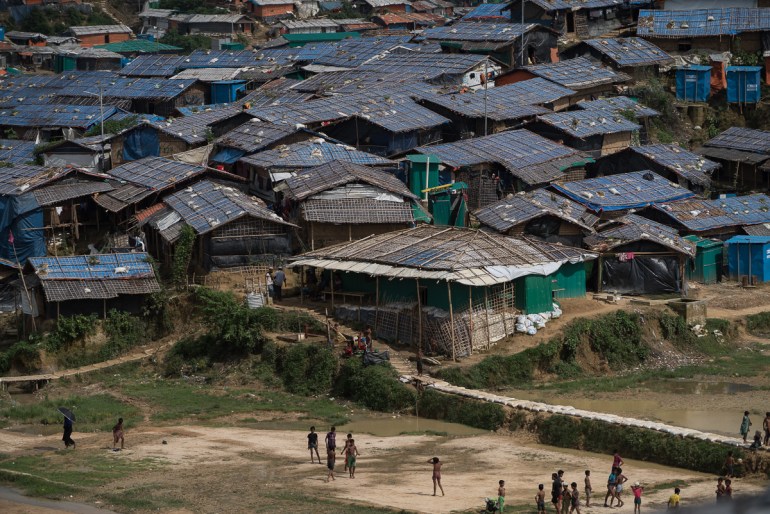

Cox’s Bazar refugee camp in southeastern Bangladesh webs together more than 30 individual camps of makeshift bamboo and tarpaulin structures. Families live in compact quarters, using communal toilets and water facilities.

Described by the United Nations (UN) as “the most persecuted minority in the world”, the state of survival for Rohingya in Bangladesh is prey to the pernicious effects of mother nature and camp life.

What it means to be stateless

The Rohingya are a mostly-Muslim ethnic group who have lived in Buddhist-majority Myanmar for centuries.

They have faced persecution at the hands of the military since the country’s independence in the late 1940s. In 1982, a citizenship law excluded the Rohingya as one of the 135 official ethnic groups in Myanmar and barred them from citizenship, effectively rendering them stateless.

As a result, Rohingya families were denied basic rights and protection, making them vulnerable to exploitation, sexual and gender-based violence and abuse.

On August 25, 2017, Myanmar’s military launched a ferocious crackdown against the country’s mostly Muslim Rohingya, driving more than 700,000 refugees into neighbouring Bangladesh.