'Disguised as tourism’: Colombia's 'VIP' migration routes

A surge in migration from Latin America to the US has led to new routes north, billed by human smugglers as ‘VIP’ options.

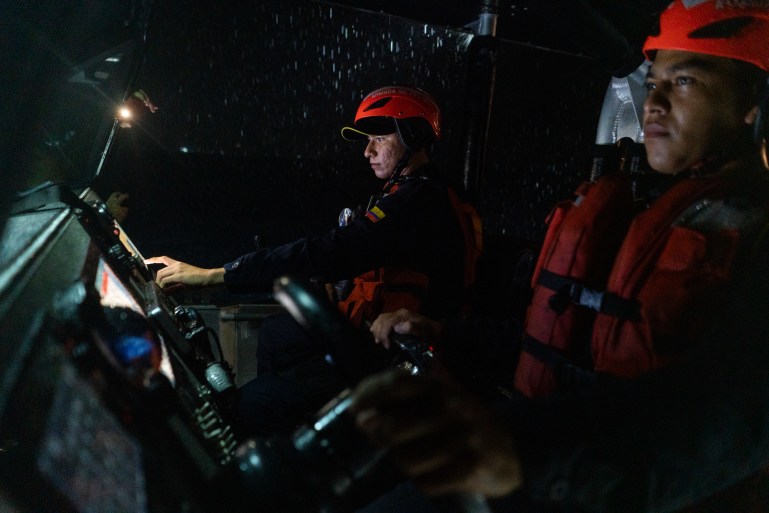

San Andrés, Colombia – Under the cover of darkness, a small team from the Colombian Coast Guard climbs on board a speed boat equipped with radar and a high-tech detection system.

It is 11pm, and the group, composed of a half-dozen young marines, is setting off to patrol the tiny coral island of San Andrés in the Caribbean Sea.

As they zip over the waves, sheets of heavy rain begin to hammer their boat, clouding their vision. But the team continues its mission, scanning the island’s east coast in search of a particular target: human smugglers, otherwise known as coyotes.

In recent years, smugglers have been offering asylum seekers and migrants alternative methods of travelling north from South America to the United States.

Those alternatives include what the coyotes bill as “VIP routes”: journeys that bypass dangerous stretches of terrain by traversing the Caribbean waters instead.

But experts warn that these overseas voyages may not be as safe as they are advertised to be.

Wrapped in a waterproof coat to stave off the rain, Lieutenant Commander Santiago Coronado, the head of the San Andrés Coast Guard, explains that the growing popularity of these “VIP routes” has led to a spike in law enforcement activities off Colombia’s coast.

“Realistically, where it’s hardest to catch them [the smugglers] is at sea,” Coronado told Al Jazeera. “We’ve increased our patrols in order to avoid people putting themselves in danger.”