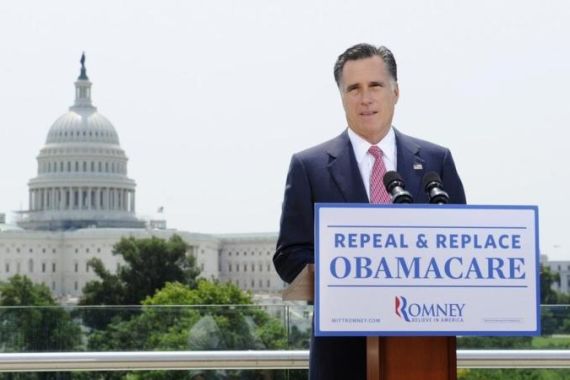

Mitt Romney’s health care dilemma

Because of the Republicans’ rightward lurch, the candidate can’t take credit for his biggest achievement as governor.

Poor Mitt Romney. I feel bad for him.

In any other election year, the Republican president hopeful might have been a formidable challenger. As governor of Massachusetts, he led the way towards universal health care, a singular achievement that any American, liberal or conservative, could rally around. His platform could have been: I made it happen in Massachusetts as governor. I could make it happen across the country as the president of the United States of America.

Many US citizens have died due to the prohibitive cost of health care, so it’s no exaggeration to suggest that this would resonate with voters, maybe enough to put him in the Oval Office. It has been six years since former Massachusetts Governor Romney signed his historic health care reform legislation into law. That state now has the highest rate of insured people (98 per cent). Emergency-room use is down there, and preventative care is up.

| US healthcare law leaves millions without coverage |

The one thing Romney can be most proud of during his one time in high public office, however, is the very thing he can’t use in this presidential election. The reason? In 2009, his Republican Party threatened any proposal by President Barack Obama that would make Medicare accessible to every US citizen. Because some Senate Democrats were afraid of the repercussions of what had been called “the public option”, an alternate version of the single-payer system preferred in other rich countries, Obama dropped the tax-based single-payer idea and offered what he thought neither Democrats nor Republicans would refuse: health care legislation modeled after the smash success of “Romneycare”.

In retrospect, it’s as if he were taking Romney’s advice.

In a 2009 opinion-editorial in USA Today, former Governor Romney clearly recommended his actions in Massachusetts were perfectly suited to US national policy, because it would control costs, keep health care in the private sector and circumvent pressure to create “a European-style single-payer system”:

“Massachusetts also proved that you don’t need government insurance. Our citizens purchase private, free-market medical insurance. There is no “public option”. With more than 1,300 health insurance companies, a federal government insurance company isn’t necessary. … To find common ground with sceptical Republicans and conservative Democrats, the president will have to jettison left-wing ideology for practicality and dump the public option.”

Yet the Republicans knew that if they struck a deal, they’d be helping Obama become a transformative historical figure like Franklin Roosevelt, and slimming the odds of re-taking the White House. How can you beat the man whose name is forever embedded in a law, Obamacare, that provides health care to all US citizens? But by pushing the issue all the way to the US Supreme Court, Republicans undermined their own objectives and, perhaps, ultimately derailed Romney’s run for president.

The ‘Obamacare’ ruling

The legal challenge brought by Republicans and their billionaire allies targeted a part of the law called the individual mandate. The mandate requires that all US citizens be insured, which means that, in theory, the rising curve of health care would slowly bend downward. The plaintiffs claimed such a rule was unconstitutional, but the court’s majority disagreed, saying that the rule falls under the power of Congress to tax and spend.

This took almost everyone by surprise. The debate had previously been about whether the mandate was constitutional under the Commerce Clause of the Constitution (which regulates interstate trade), but now the debate was about whether the mandate was in fact a tax (because you pay a penalty proportional to your income if you don’t buy health care).

Romney had never used the word “tax”. Neither had Obama. But the highest court in the land was calling it a tax, and the Republicans reflexively pounced, claiming that Obamacare is the largest tax increase in history (it isn’t, by far). They thought they’d inflict damage to Obama’s campaign, but didn’t realise they would be doing the same thing to Romney’s.

Since the court’s ruling last week, the Romney camp has been pushing back against Republican efforts to paint Obama as a tax-and-spend liberal, because that might end up forcing Romney to abandon his signature achievements as Massachusetts governor or risk becoming the rare presidential candidate who has alienated his own political party.

There may be no turning back. Romney and the Republicans have spent the past two and half years distancing themselves from the health care law, especially the individual mandate. Now they have made plenty of room for Democrats to move in. And they have. Not only has Obama embraced the moniker “Obamacare” (so much so that it is starting to sound like an honourific more than a slur), but the Democrats have mastered Romney’s rhetoric in bringing “Romneycare” to fruition in Massachusetts.

In his op-ed, Romney said the use of “penalties” or “tax credits … encourages ‘free riders’ to take responsibility for themselves rather than pass their medical costs on to others”. Last weekend, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi said virtually the same thing when she told “Meet the Press”: “It’s not a tax on the American people. It’s a penalty for free riders.”

And Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley, speaking for the president, repeated the talking point when he told “Face The Nation”: “The massive so-called tax increase they’re talking about is the freeloader penalty, which would affect at most 1-2 per cent of people that could afford health care and instead want to be freeloaders on the rest of us with uncompensated care.”

|

“Romney might have been the perfect candidate in 2008, but that was before his party took a drastic turn to the right to indulge its worst tendencies.” |

Romney can’t take credit

Mitt Romney’s pioneering health care reform served as the model for the biggest domestic policy legislation since Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, and yet he can’t take any credit for it, because of his own party’s desire to demonise Obama’s fairly modest calls for reform. At the same time, Romney is now alienated from the political party that forced him to abandon his admirable record, because so many of the GOP’s conservatives have drunk their own Kool-Aid; they faithfully believe Obamacare is a tax levied to pay for a “socialised” health care system – even though “Romneycare” was designed to be exactly the opposite.

About all Romney can do now is call for the law’s repeal, but even that’s losing credibility fast. The more people learn about Obamacare, the more they like its provision. It happened in Massachusetts, too. About 60 per cent of residents now approve of the law, double that of Obamacare.

Even if Romney wins and Republicans take both chambers of Congress, repeal is unlikely. As Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said in an interview, the odds of unravelling a massive law of Obamacare’s size are slim. “If you thought it was a good idea for the federal government to go in this direction, I’d say the odds are still on your side,” he said. “Because it’s a lot harder to undo something than it is to stop it in the first place.”

And besides, repeal is increasingly sounding like sour grapes. If Republicans were to repeal the law, they’d be obliged to replace it with something. Turns out, they’d replace it with components similar to Obamacare’s. US Representative Allen West, a staunch Tea Party libertarian, suggested as much when asked what Republicans would do if the Supreme Court struck down the law. That suggests that Republicans don’t hate Obamacare so much as they hate the president’s name being permanently associated with it.

Romney might have been the perfect candidate in 2008, but that was before his party took a drastic turn to the right to indulge its worst tendencies. Instead of running as the first man to make the dream of universal health care a reality, he has to run against the man who has made the dream of universal health care a reality for every US citizen. That’s got to hurt deep down, and that’s why I feel bad for Mitt Romney. History hasn’t been kind so far, and it’s unlikely to get better soon.

John Stoehr’s writing has appeared in American Prospect, Reuters, the Guardian, Dissent, the New York Daily News and The Forward. He is a frequent contributor to the New Statesman and a columnist for the Mint Press News.