The US Senate at work: Defeating background checks for gun purchases

The US Senate failing to pass a gun background check amendment exposes the flaws in the electoral process.

Earlier this week, the United States Senate failed to approve an amendment calling for stricter background checks on gun purchases. Much has been made of the fact that close to 90 percent of the country supports some form of increased background checks, as well as the fact that Senate rules required 60 votes for the measure to pass, as opposed to a simple majority, by which the measure would have passed.

Left less discussed, however, is the fact that once again we are able to see the effect of the electoral rules used to elect the Senate. The United States uses an extremely disproportionate system to elect its Senators. Every state, from Wyoming with its 564,000 people to California with its 37.25 million people, gets to elect two Senators. That means when votes on bills such as gun control are being held in the Senate, Wyoming’s half a million people are entitled to the same number of votes as California’s 37 million.

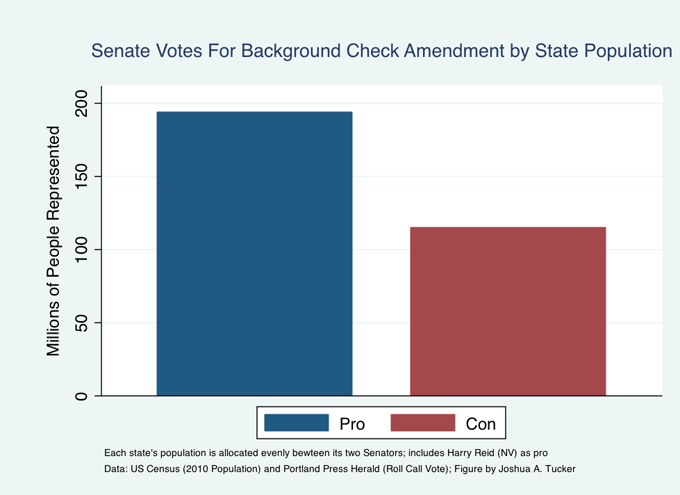

The consequences of this arrangement can be seen in the above figure. If we make – the admittedly simplistic – assumption that each United States Senator “represents” half of the residents of her or his state, then another way to total the votes in the background checks amendment is to count how many “people” – via their Senator’s vote – supported the amendment and how many people opposed it as realised in Senate voting (Note: all of the substantive conclusions I make and the percentages I report would be the same if I assumed all Senators represented their whole state’s population and that each person in the United States is represented in a Senate vote twice – the calulations are mathematically equivalent).

This is certainly a crude measure – of course some residents of Wyoming (both Senators opposed) support the measure, and some residents of California (both Senators supported) oppose the measure – but if we assume Senators are trying to represent the interests of the citizens of their state (see here for some strong evidence that voting by Senator is closely related to public opinion by state), then it is a relatively good proxy. Another way to think of this is as if we were to weight each Senator’s vote by the size of the population in his or her state, then the background check measure would have received 63 percent of these population-weighted votes. This is in contrast to the 55 percent of actual Senate votes the measure received (Note that in both calculations I am counting Democratic Senator Harry Reid of Nevada of having supported the measure; Reid actually switched his vote at the last moment for procedural reasons). Thus if the measure need 60 percent of population-weighted Senate votes, it would have passed.

It is also interesting to note that the four Democratic Senators (one each from Alaska, Arkansas, Montana, and North Dakota) who broke ranks and opposed the measure combined represent only 0.86 percent of the population by my coding rules, thus their votes had more than four and a half times the effect on the outcome their population weighted votes would have had. In contrast, the four Republican Senators that broke ranks and supported the measure (one each from Arizona, Illinois, Maine and Pennsylvania) combined to represent 5.4 percent of the population of the country.

So while there are certainly many explanations for why the United States Senate rejected a measure supported by a large proportion of the country – including interest group politics and the voting rules within the Senate – the outcome is yet another example of the consequences of the disproportional electoral rules that continue to be used to elect Senators in the United States.

Joshua A Tucker is a Professor of Politics at New York University, a National Security Fellow at the Truman National Security Project, and a co-author of the award-winning politics and policy blog The Monkey Cage.

Follow him on Twitter: @j_a_tucker