National media failing Kenyans on Pandora Papers

Kenyan media are doing a disservice to the public by framing the revelations as an issue of legality rather than ethics.

The publication of the Pandora Papers, a significant investigation into how world leaders and public officials use offshore tax havens to hide assets worth hundreds of millions of dollars has caused a bit of a stir in Kenya. However, by and large, the reaction of the Kenyan media has served to shed more darkness on an already obscure subject.

Among those whose overseas financial arrangements have been exposed are the family of President Uhuru Kenyatta, whose father, Jomo Kenyatta, was Kenya’s first president. That the Kenyattas, and other political families, have been stashing massive sums of money abroad will come as no surprise to anyone with a passing knowledge of Kenyan history. Easily the richest family in the land, there have long been complaints about how the wealth of the Kenyatta family was (and continues to be) acquired. The recent revelations about where it is kept will simply pour more fuel on the fire.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsOn rich, famous ‘cockroaches’ and tax evasion

Chile’s billionaire president under scrutiny over Pandora leak

Sri Lanka probes president’s niece over Pandora Papers claims

Even before he became president in 1964, Jomo Kenyatta was known for his problematic relationship with other people’s money. In the book Kenya: A History Since Independence, historian Charles Hornsby notes that as far back as 1947, people had noted Kenyatta’s “desire for money and difficulties in separating his personal financial affairs” from those of the institution he was running. These traits would attain full expression during his 15-year rule and beyond.

Functionally broke when he entered State House, by his death in 1978, his family would boast, according to the American spy agency CIA (PDF), “extensive holdings of farms, plantations, hotels, casinos and insurance, shipping and real estate companies” with members of the family occupying top public office and influential posts in large foreign-owned industrial companies doing business in Kenya. The family would also be deeply involved in the ivory and charcoal trade which decimated Kenya’s elephants and forests.

Today, the family has fingers in almost every pie in the Kenyan economy and has continued to exploit its privileged position to milk Kenyans. In 2017, one scholar described a partnership between the family’s bank and Kenya’s largest mobile service provider to offer extortionate mobile loans to the majority of adult Kenyans as “the extraction of surplus on a national scale for the substantial benefit of one politically connected family”. Within the first 14 months of the arrangement, the bank was dispensing more than 24,000 loans daily at an annualised interest rate of 90 percent, and more than 140,000 borrowers had been blacklisted by credit reference bureaus for defaulting on the loans.

Where does all the money extracted from poor Kenyans go? Kenyans got a clue in 2007 with the leak of a report by the international risk consultancy, Kroll, by the whistle-blowing website, WikiLeaks. In one of its first major scoops, the website released details of the 110-page investigation into the looting of Kenya during the regime of Daniel Arap Moi, who succeeded Jomo Kenyatta in 1978, which had been commissioned (and buried) by Moi’s successor and Uhuru Kenyatta’s predecessor, Mwai Kibaki.

The report revealed how Moi’s family had created “a web of shell companies, secret trusts and frontmen” to funnel more than $1.3bn into nearly 30 countries including the United Kingdom. It is notable that the Pandora Papers leak has shown that the Mois and the Kenyattas shared the same consultants, from the private wealth division of the Swiss bank UBP, who helped them hide and stash their money overseas.

Given the above, it is surprising that Kenyan media have opted to frame the release of the papers as an issue of legality rather than ethics. The repeated refrain is that there is no evidence the Kenyattas broke any laws with short shrift given to questions about the advisability of allowing public officials – who are paid to fix local problems – to not only stash money abroad, boosting foreign economies, but, perhaps more importantly, to also hide their ownership of it. When the Kenyattas and others who have relatively easy access to public money can effectively disguise what they own in a confusing, Matryoshka doll complex of foreign briefcase companies and foundations, how can the public ever trust that it is not being robbed?

This is even more so the case given the ongoing attempts to extradite two former officials for laundering close to $10m in bribes through the British tax haven of Jersey.

The Pandora Papers come as Kenya is engaged in a discussion about wealth declaration laws prompted by the government’s public outing of the riches belonging to Kenyatta’s deputy, William Ruto – another politician linked to the massive looting enterprise that is the Kenyan government – after the two had a falling out. Kenyatta and his cronies have been trying to undercut Ruto’s bid to succeed him as president in next year’s elections by exposing the fallacy of Ruto’s cynical and populist attempt to paint himself as one with the common masses he is suspected of robbing.

Kenyan public officials and their immediate families are required by law to file wealth declaration forms every two years, but in a typically self-defeating move, the declarations are kept confidential with penalties of up to five years imprisonment for publishing or otherwise disseminating the information. It is thus unclear whether Kenyatta and other politicians have actually complied with the law and declared their hidden assets abroad.

The Pandora Papers also present an important opportunity to discuss the culpability of Western professionals, banks and jurisdictions in enabling the accumulation and camouflaging of illicit funds by public officials and their families. According to Tax Justice Network Africa, for every dollar of development aid that comes to the continent, $10 has left in the form of IFFs, tax evasion and avoidance as well as corruption. And much of this money ends up in Western economies – as the Kroll report and the Pandora Papers have demonstrated.

“Tax havens play a facilitatory role in human rights abuse by providing an avenue for hiding and laundering money which has been … acquired under dubious circumstances” such as corruption, writes Robert Mwanyumba of the East Africa Tax and Governance Network. And it is the countries that shout the loudest about corruption that run and benefit from these havens.

The British Virgin Islands, where the Kenyattas incorporated one of their shell companies, is part of what has been described as a “Spider’s Web”, which the Tax Justice Network calls “a network of British territories and dependencies [where the UK government has full powers to impose or veto lawmaking] that operates as a global web of tax havens laundering and shifting money into and out of the City of London”.

In fact, according to the Financial Secrecy index 2020, two-thirds of the top 12 most important financial secrecy jurisdictions are either in the US, Western Europe or British Overseas Territories. When treated as a single entity, the UK and its web rank at the very top of this index of abettors of theft and corruption.

The reporting by Kenyan media therefore does Kenya and Kenyans a great disservice. By focusing on the legalities and ignoring the ethics, it strips the issue of its potency as a driver for change and allows politicians to distract from what’s important.

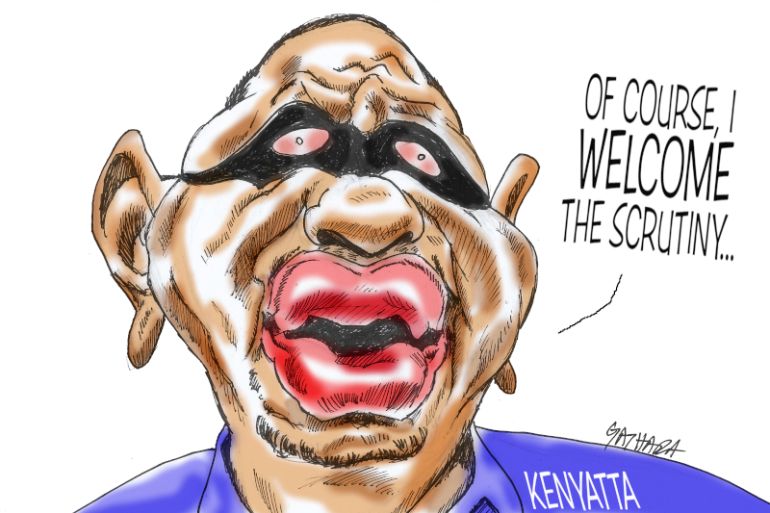

Already, President Kenyatta has welcomed the Pandora Papers as “enhancing the financial transparency and openness that we require in Kenya and around the globe” and acknowledging that “the movement of illicit funds, proceeds of crime and corruption thrive in an environment of secrecy and darkness”. One could be forgiven for imagining that it is not his own and his family’s lack of transparency over the source of their wealth as well as their attempts to cloak the funds “in an environment of secrecy and darkness” that is in question.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.