Chilean democracy faces a critical test

If far-right candidate Kast wins the upcoming presidential election, Chile could find itself on a path towards democratic backsliding.

On December 19, far-right candidate José Antonio Kast will face off against Gabriel Boric of the Apruebo Dignidad left-wing coalition in Chile’s second-round presidential election.

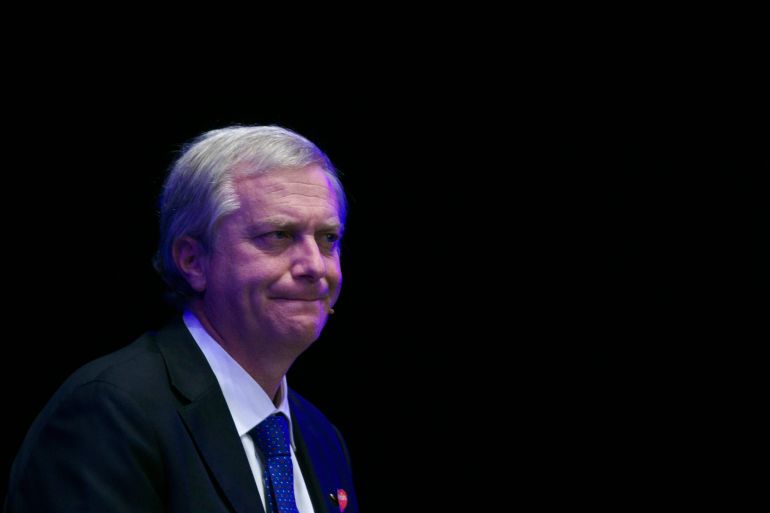

Kast, a 55-year-old lawyer and former congressman, garnered more votes in the first-round election last month, but Boric, a 35-year-old congressman and former student activist, has since been leading with a small margin in recent polls.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsNorth Macedonia votes in presidential polls as EU membership bid looms

‘Absolute power’: After pro-China Maldives leader’s big win, what’s next?

Solomon Islands pro-China PM Manasseh Sogavare fails to secure majority

Kast, who has been compared with Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, unapologetically defends former dictator Augusto Pinochet, who killed, disappeared and exiled thousands of Chileans during his brutal reign between 1973-1990.

Chile’s election unfolds amid a crisis of democratic legitimacy that became apparent with massive street protests over inequality and political discontent in 2019. According to a 2021 Vanderbilt University study, Chile has Latin America’s fourth lowest level of satisfaction with democracy, at 29 percent. Only Colombia, Haiti and Peru perform worse.

Chile’s democratic crisis has been brewing for years. The country’s out-of-touch political class has repeatedly failed to renovate parties and include younger generations and other marginalised groups in the political process.

As a result of the 2019 protests, leaders from Chile’s main political parties announced an agreement to rewrite the constitution that was adopted by Pinochet in 1980. The accord appeared to signal a new era of politics – one that seeks to rebuild trust in institutions and create a more inclusive political system, overcoming legacies of the dictatorship.

With Kast’s success at the polls, this political shift feels less certain. Kast ran a hard law and order campaign in the first round. He painted Boric’s promises to reform the welfare state as extreme and dangerous, appealing to the deeply rooted anti-Communist sentiments that were fomented by Pinochet for years. By contrast, he has paid little attention to Chile’s high levels of inequality – a key driver of the 2019 protests.

Chileans’ frustration with inadequate pensions, healthcare and employment will not disappear if Kast wins on December 19. Economic hardship and social inequality have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Kast’s indifference to these problems would likely reignite protest, but the far-right candidate has stressed that his government would respond harshly to any such unrest. This could plunge Chile into a dangerous cycle of violence, protest and repression that would strain democracy by further polarising society and undermining institutional channels of conflict resolution.

A Kast presidency could also endanger Chile’s constitutional rewrite, and by extension, the country’s best chance at resolving the continuing crisis of democracy. In October 2020, 78.3 percent of Chileans voted for the constitution to be rewritten. Kast, however, opposes the process and might undermine the constitutional convention and its work. If the constitutional rewrite fails, Chile’s problems of disaffection and anti-system politics could worsen, deepening instability.

While some of Kast’s support comes from citizens nostalgic for the dictatorship, the collapse of Chile’s traditional parties helped him reach beyond that base. During his first-round campaign, Kast promised to impose order and crack down on crime. He also promised to close Chile’s borders to undocumented immigrants and build trenches to stop illegal crossings. These messages appealed to anxious, conservative voters, who have grown tired of social conflict and who are wary of deep changes underfoot in Chile. Their anxiety was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has driven up unemployment, poverty, and more recently, inflation.

Boric pulls support from younger sectors in urban centres and he enjoys an advantage among female voters. These groups drove the 2019 protests, which although massive in scope, were unorganised and thus difficult to transform into an electoral movement. Boric and his coalition have not addressed this challenge, failing to build strong party organisations that can mobilise voters. In the first round of the election, this resulted in weak support for Boric in some of Chile’s traditional left strongholds, such as the northern mining regions.

In the second round, Boric shifted his campaign’s focus, emphasising the benefit of a stronger welfare state and a new constitution for advancing social peace and security in Chile. The left-wing candidate also sought to highlight Kast’s anti-democratic tendencies. Polls suggest this new focus has increased Boric’s support, yet a large share of voters remain undecided and others report that they will abstain on December 19.

Countries around the world have experienced democratic backsliding in recent years and Chile is not immune to the trend. Those who continue to celebrate the country’s strong and stable democracy overlook clear signs of distress – declining trust in institutions and the collapse of political parties. A Kast presidency would exacerbate these problems by ignoring widespread discontent over inequality and jeopardising the new constitution. This could further erode institutional strength and put Chile on a path towards democratic backsliding.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.