Human rights defenders continue to be killed with impunity

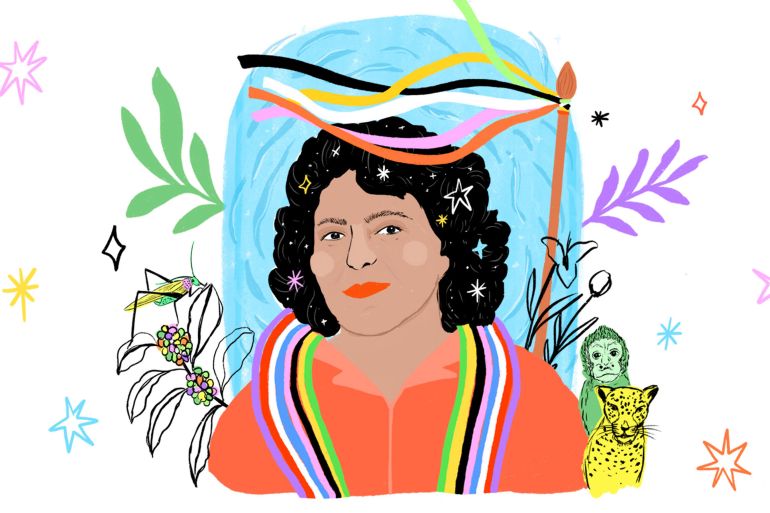

Five years after Berta Cáceres was murdered, governments are still failing to protect human rights defenders.

It has been five years since environmental human rights defender Berta Cáceres was murdered in her home in Honduras.

She was one of hundreds of human rights defenders killed that year because of their peaceful work. Hundreds have been killed every year since, but those responsible have rarely been brought to justice. Although some have been convicted of Cáceres’s killing, others believed to have been involved are still to be held to account.

It is a familiar and continuing story, in Honduras and across the world, where those responsible for the murder of a human rights defender often enjoy impunity.

This week I am presenting my latest report to the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, and it is on the killings of human rights defenders and the threats that often precede them.

At least 281 human rights defenders were killed in 2019, with a similar number expected to be recorded for 2020. Unless radical, immediate action is taken we can expect hundreds more murders this year.

Since 2015, at least 1,323 defenders have been killed. While Latin America is consistently the most affected region, and environmental human rights defenders like Cáceres often the most targeted, it is a worldwide issue.

Between 2015 and 2019, human rights defenders were killed in at least 64 countries, which is a third of all UN member states. Those collecting the data agree that underreporting is a common problem. The number of defenders killed is likely significantly higher than the figures we have.

We know that on every continent, in cities and the countryside, in democracies and dictatorships, governments and other forces threaten and kill human rights defenders. Many, like Cáceres, are murdered in the context of large business projects.

Why do so many governments and others kill human rights defenders working peacefully for the rights of others? Partly because they can, because there is unlikely to be the political will to punish the perpetrators.

While some states, particularly those with high numbers of such killings, have established dedicated protection mechanisms to prevent and respond to risks and attacks against human rights defenders, defenders often complain that the mechanisms are under-resourced.

And in too many cases, businesses are also shirking their responsibilities to prevent attacks on defenders or are even responsible for the attacks.

These murders are not random acts of violence that come out of nowhere. Many of the killings are preceded by threats. As Amnesty International has noted, Cáceres’s murder “was a tragedy waiting to happen”, as she had “repeatedly denounced aggression and death threats against her. They had increased as she campaigned against the construction of a hydroelectric dam project called Agua Zarca and the impact it would have on the territory of the Lenca Indigenous people.”

And yet her government failed to protect her, as so many governments fail to protect their defenders. Since I took up this mandate in May 2020, I have spoken to hundreds of human rights defenders. Many have told me about their real fears of being murdered, and have shown me death threats made against them, often in public.

They tell me how some threats shouted in person, posted on social media, delivered in phone calls or text messages, or in written notes pushed under a door. Some are threatened by being included on published hit lists, receiving a message passed through an intermediary or having their houses graffitied. Others are sent pictures through the mail showing that they or their families have been under long-term surveillance, while others are told their family members will be killed.

I have been told by defenders about a coffin being delivered to the office of an NGO; a bullet being left on a dining room table in their home; edited pictures of them being posted on Twitter, showing them having been attacked with axes or knives; and an animal head being tied to the door of their organisation’s office.

Those advocating for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex rights, and women and transgender human rights defenders, are often attacked with gendered threats, and targeted because of who they are as well as what they do. Women and LGBTQ people demanding rights in patriarchal, racist, or discriminatory contexts often suffer specific forms of attack, including sexual violence, smears and stigmatisation.

The murders of human rights defenders are not inevitable, many are signalled in advance, and yet governments fail, year after year, to provide enough resources to prevent them, and fail, year after year, to hold the murderers to account. In fact, states should not only end impunity but also publicly applaud the vital contribution that human rights make to societies.

This week I will again remind the UN that their members are failing in their moral and legal obligations to prevent the killings of human rights defenders. It is no use for government officials to wring their hands and agree that the murder of Cáceres and other defenders is a terrible problem and that someone should do something about it.

It is not that complicated. It is up to states to find the political will to prevent killings by responding better to threats against human rights defenders, and to hold murderers to account.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.